When my sister Belinda and I wrote Searching for Charlotte: The Fascinating Story of Australia’s First Children’s Author, we originally planned a chapter in which we explored Charlotte Waring’s family ancestry. However, by the time we had written the book, it was too long (a very common problem!)

So I reluctantly cut out the chapter I had written about the Waring family. The research had taken me months to do, and I had loved writing it. But of all the chapters in the book, it was the least important. We wove a little of it into one of Belinda’s chapters (if you’ve read the book, you’ll recognise which bit, I’m sure.)

However, I thought I’d share the lost chapter with you, just in case you’re interested. It’s all about William the Conqueror and the Battle of Hastings and the Bayeux tapestry, so as you can see it really does not have much to do with my ancestor Charlotte’s journey to write Australia’s first children’s book. Nonetheless, I hope you find it interesting. Happy reading!

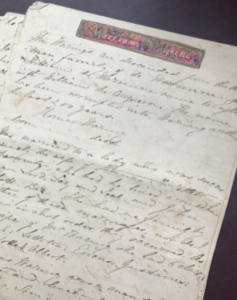

Buried deep in the archives at the Mitchell Library, the oldest library in Australia, is a folder containing a sheaf of loose pages, inscribed in elegant nineteenth-century calligraphy. They were written in 1872 by my great-great-great-great-aunt, Louisa Atkinson, the first Australian-born female novelist, for a baby daughter she would never see grow up.

The first page is headed by the words ‘Warrenne Waring’, beautifully drawn and coloured, for Louisa Atkinson was an artist as well as an author.

Outside, the rain beats down on the pavement and umbrellas jostle for space. Inside, the sacred hush is occasionally disturbed by a murmur of voices or the rustle of paper. It’s Wednesday, 21st September, and my sister Binny and I have come together to read these old, fragile, difficult-to-decipher pages as our very first act of research together. We know that they contain a brief history of our family.

The opening lines read: ‘The Warings are descended from the Norman family of de Warrenne. William de Warrenne came to England with William the Conqueror. The name has been corrupted into Waring within the last two hundred years.’

The first page of Louisa Atkinson’s handwritten family memoir

Image source: The Mitchell Library

This is not a new discovery for us. When we were children, our grandmother had often told us that Charlotte Waring’s ancestors came from France to fight at the Battle of Hastings.

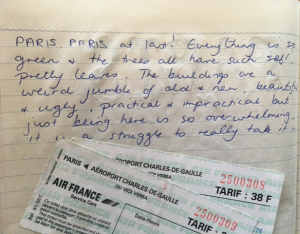

Even though William the Conqueror invaded England in 1066, nine hundred years before I was born, I was always proud of my drop of French blood. I imagined it gave me a certain flair for clothes. I read biographies of Colette and Anaïs Nin and Coco Chanel, and visualised myself sitting at a cafe on the Left Bank, wearing a velvet beret and drinking absinthe as I wrote ecstatic poetry.

When I was in my mid-twenties, I travelled overseas for the first time. I went with the man who would one day be my husband. We flew straight to Paris, the place I had most longed to see. On arrival, I wrote in my diary: ‘PARIS. PARIS at last!”

A page from Kate’s diary, 10th September 1991

I have been to France many times since then.

In the summer of 2016 – nine hundred and fifty years after William the Conqueror and his knights set sail from Normandy - I travel to Bayeux with my friend Susie to see the famous tapestry. In French, it is known both more poetically and more precisely as La Broderie de Bayeux, for it is an artwork embroidered by hand in seven different coloured threads on a very long strip of linen.

Bayeux is one of those rare places in the world where time seems woven of the most fragile of fabrics. It was the first town to be liberated by Allied forces on 7th June 1944 - the morning after D-Day – and so it escaped much of the bombing other Norman towns suffered. Half-timbered houses lean over narrow cobblestone streets, and an old mill-wheel churns the water flowing under an arched stone bridge. The tall pointed spires of the cathedral soar into the twilight-blue sky. Inside the nave, a young girl in a long white dress curtsies to the altar and crosses herself. The last of the sunlight shafts through intricate stained glass upon the marble floor, worn into hollows where generation upon generation have knelt and prayed.

As we wander through the old town in the warm dusk, iron lanterns kindling above ancient wooden doors, it is easy to imagine knights in heavy armour clopping through the square upon their destriers, young women in gowns with dangling sleeves throwing flowers.

Susie and I are the first in the queue at the Bayeux Tapestry Museum the following morning. Slowly we pass through the long curving tunnel where the embroidery is housed behind protective glass. It has been described as the world’s first cartoon strip: it is more than 70 metres long but only 50 centimetres high, and the story unfolds as a sequence of vividly rendered scenes, like the storyboard for a film.

As I examine each tiny stitch, I wonder if any of these men seen fighting, burning and killing was William de Warenne, or if that brown splotch was a bloodstain from the pricked finger of his wife-to-be Gundred, one of the queen’s ladies-in-waiting rumoured to be an illegitimate daughter of the Conqueror. I wonder how they met, and if they loved each other, and if they were happy.

I tell Susie that my family is descended from one of these Norman knights, then laugh. I say, ‘Maybe it’s not true. Maybe it’s just a story.’

I don’t want to seem as if I’m boasting. Everyone is descended from someone. It’s just that my family is lucky enough to have literate forebears whose lives were documented in the historical record. Very few people can say the same. In England in the 16th century, 500 years after the Norman invasion, 90% of men and 99% of women could not read or write. This seems so sad. Their lives were – as engraved on the poet John Keats’s grave in Rome – ‘writ in water’.

The story of my ancestors begins in the 9th century when a fleet of Vikings sailed up the Seine to Paris, which was just a small walled village on a little island in the middle of the river.

Paris had been looted numerous times before, and so had built fortified bridges across the river to block the longboats. The Vikings were repulsed, but settled in for a long siege.

After almost a year, the king of France came to help. He drove off the invaders but then offered one of the leading jarls all the land between the mouth of the Seine and Rouen in return for protection against further Viking raids. The warrior who won all this rich and fertile land was named Hrólf the Walker, because he was so huge no horse was strong enough to carry him. He became Count Rollo of Normandy, his lands named from the Old Norse word Norðmaðr or ‘northman’.

Rollo consolidated his power by marrying into the highest level of French nobility. His son was William Longsword, and his grandson was Richard I, known as the Fearless.

One day Richard went hunting in the forest, and stayed the night at the house of one of his foresters. The forester, it was said, had a most beautiful wife named Sainfrida. As soon as Richard saw Sainfrida, he wanted her. He asked her to come to his bed that night.

Sainfrida had no wish to be seduced by the duke, but did not like to displease him. So she decided to trick the duke by sending one of her unmarried sisters to his bed in her place. Her youngest sister Gunnora agreed to the substitution, and made her way in the darkness of the night to Richard’s room.

The duke was so delighted with Gunnora that he forgave Sainfrida for her trick, and thanked her for saving him from the sin of adultery. He married the forester’s daughter, and they had three sons and three daughters together. Her other sisters and brother married into Norman nobility, and in time their descendants (which included my ancestor William de Warenne) formed a powerful and loyal following for the dukes of Normandy.

Gunnora’s eldest son inherited the dukedom on his father’s death in 996, and became known as Richard the Good. His sister Emma was married to the English king, Ethelred the Unready. After Ethelred died, Emma was forced into marriage with Canute, who had invaded England and won its throne in 1016. He is most famous for proving that no king, no matter how powerful, could turn back the tide. Emma’s marriage is significant because she was the only woman in history to marry two kings of England; and because later it gave her grand-nephew, William the Conqueror, a claim to the throne of England.

Richard the Good died in August 1026, and the duchy of Normandy was inherited by his eldest son, also called Richard, who was then in his 20s. His younger brother Robert was discontented with his inheritance and rebelled, laying siege to the castle of Falaise.

One day, he noticed a beautiful young woman washing her linen in the castle moat. She was a peasant girl, and her father was a tanner of hides. She noticed the young nobleman staring at her, and hitched up her skirts so he could see her shapely legs. Robert was immediately smitten and ordered her brought to him through the back door.

The young woman – whose name was Herleva – refused.

‘I will only enter the duke’s castle on horseback through the front gate,’ she declared. Robert eventually agreed, and Herleva rode proudly through the castle gate on a white horse.

That night, she dreamed a tree sprang from her womb. It grew so tall and strong its shadow darkened all of Normandy, then stretched across the sea to eclipse the kingdom of England. A few weeks later, Herleva discovered she was pregnant.

Soon after, her lover Robert was captured by his brother, the duke. After Robert swore an oath of fealty, the duke rode back to Rouen where he died suddenly and suspiciously. He had ruled for less than a year.

Robert promptly declared himself the next duke. Herleva’s son was born soon after. He was known as Guillaume le Bâtard, or – in Anglicised form – William the Bastard. Six years later, his father the duke decided to go on pilgrimage to Jerusalem. Some suggest that Robert was haunted by guilt over the murder of his brother, others that he sought absolution for his many affairs with women. Whatever the reason, he never returned. He died in what is now Turkey in July 1035.

His son William was only eight years old.

It is at this point in the long and bloody history of Normandy that the de Warennes first enter the written record.

Sometime between 1037 and 1055, a man named Rodulfo Warethnæ agreed to sell land to the Abbey of the Holy Trinity, which lay outside the city wall of Rouen. Another charter named his wife as Beatrice. She is believed to be Beatrice de Vascoeuil, the grand-daughter of Duchess Gunnora’s sister, Avelina. This means that she was Duke Robert’s second cousin.

In 1059, a man named Rodulfus de Warenna sold another four parcels of land to the same abbey, with his wife Emma as his witness. For a long time, it was thought that Rudolfo/Rodulfus were the same man with two different wives. However, recent research indicate the charters refer instead to a father and his son.

The situation is complicated by the lack of standard spelling. Records of the time sometimes spell the same name in different ways in the same document. Rodulfus appears as Ralph, Ranulph, Ranulf, Rodolph or Rudolph, the name most modern-day historians use. Similarly, my ancestors’ last name appears as de Warenne, de Warrenne, de Varenne and de Warethna. (The family’s surname is said to be a reference to the village of Varenne, named for the river on which it was built.)

When Rudolph’s wife Emma bore him a son in 1036 – the year after Guillaume le Bâtard inherited the dukedom – he was named Guillaume in honour of his illustrious kin. The two Williams were only nine years apart in age, and grew up in a close-knit family which included William FitzOsbern, Roger de Beaumont and Roger de Montgomery, all of whom were descendants of Duchess Gunnora’s brother and sisters.

The boys grew up in a state of anarchy. The Norman aristocracy battled each other and outsiders for control of the young duke. Four guardians appointed to care for him died in swift succession, one being murdered in the boy’s bedchamber while he slept. It is said the duke’s uncle sometimes had to hide him in the houses of peasants to keep him safe.

Duke William needed powerful allies, and so he needed to marry well. He chose Matilda of Flanders, the French king’s niece. According to legend, when he sent his envoy to ask for Matilda's hand in marriage, she told the knight that she was far too high-born to consider marrying a bastard. After hearing this response, William rode from Normandy to Bruges, found Matilda on her way to church, dragged her off her horse by her long plait, threw her down in the street in front of her flabbergasted servants, and galloped away. After that, Matilda refused to marry anyone else. Not even a papal ban (on account of them being cousins) could dissuade her. They were married in 1051.

The king of France did not seem pleased at this rather violent romance. In February 1052, he led a double-pronged force against Normandy. Henry I led the main thrust through Évreux, while his brother Odo invaded eastern Normandy.

In response, Duke William divided his troops into two. He galloped to meet Henry to the west of the River Seine, while some of his supporters rode to face Odo.

William de Warenne was just eighteen years old, the younger of two sons, and eager to make his way in the world. He seized his sword, saddled his horse and rode off to fight for his cousin, the Bastard.

For hours, the battle raged. The French forces had not expected much resistance and the Normans took them by surprise. The French suffered heavy losses, and the capture of some of their most important leaders. When news of the Norman victory reached the other side of the river, the French king withdrew in disarray.

William de Warenne was rewarded for his loyalty and valour with land near a small village on the Varenne river, which winds its sinuous way through the meadows and forests of the Orne. He built a fortified castle high on a hill above the village, with two tall round towers guarding a drawbridge. The castle was named Bellencombre, the first syllable meaning ‘beautiful’ and the second from the Old French word ‘combre’ which means ‘barrier’ or ‘obstruction’.

At Bellencombre, William de Warenne was able to enjoy the peace he had so bravely helped to win.

New Star, New King

In 1066, Edward the Confessor, the king of England, died without naming an heir.

Four rivals claimed the throne.

The first was Edgar the Atheling, a sickly fourteen-year-old boy who was the grandson of Edward the Confessor’s half-brother. Although he was the closest in blood to the crown, he had lived in exile in Europe all of his life and had few friends in England.

The second was William the Bastard. He was the dead king’s first cousin, once removed, since his great-aunt Emma was Edward the Confessor’s mother. After Cnut invaded England in 1016, Edward had fled to Normandy and had lived there for many years. William the Bastard claimed that Edward had promised him the throne in thanks to Normandy giving him shelter for so long.

The third was Harald Hardrada (which means ‘hard ruler’.) He was a fierce and ambitious Viking who had won himself the throne of Norway, tried and failed to win the throne of Denmark, and so had set his sights on winning England’s. Harald Hardrada’s claim was flimsy as gossamer, but backed up by brute force.

Finally, the fourth claimant was Harold Godwinson, a powerful English nobleman who was married to Edward’s sister Edith. Although he had no royal blood, he claimed that he had promised Edward on his death-bed to take the crown and protect England. There were, unfortunately, no witnesses to this promise. Nonetheless, the assembly of English nobles and councillors voted to elect him king, unsurprisingly preferring a rich and powerful Englishman over a sick boy, an illegitimate Norman duke, and a voracious Viking marauder.

William the Bastard was annoyed. A few years earlier, Harold Godwinson had visited Normandy, either by mistake (he was shipwrecked on its wild coast), or by design (he was sent by Edward to confirm the offer of the crown to William.) The Normans claimed the latter, and also that Harold swore a sacred oath to uphold William’s claim on the English throne. This moment is immortalised in the famous Bayeux tapestry, with Harold (looking most unhappy) laying his hand on holy relics and swearing fealty to the Norman duke.

Harold Godwinson makes his oath of fealty to William, Duke of Normandy

Image source: bbc.co.uk

The Bayeux embroidery was commissioned by William’s half-brother Odo, and so cannot be relied on for historical accuracy. Nonetheless, the crowning of Harold as king of England prompted William to call his knights together and plan the invasion of England. Many of the nobles were hesitant about taking such drastic action. Normandy did not have a navy, and was surrounded by enemies on all sides.

However, in late April 1066, a bright comet was seen in the night sky. An observer in Italy wrote: ‘a comet … appeared in the West in the evening of the 24th and (shone) like the eclipsed Moon, the tail off which streamed like smoke up to nearly half the sky.’

When William saw it, he called it ‘a wonderful sign from heaven’, and convinced his barons that it was a sign of victory to come. The Norman knights took up a new rallying cry: ‘nova stella, novus rex’ which means ‘new star, new king’.

In England, the comet was seen with dread. One monk bowed down in terror and crying ‘thou threatenst my country with utter ruin.’ King Harold was said to have dreamed uneasily of ghostly ships.

Man-at-arms warning Harold of the disastrous omen of Halley's Comet.

Bayeux Tapestry, detail (ca. 1070–80).

Image source: Wikimedia Commons - Myrabella

William the Bastard set sail in mid-September 1066, after a night spent praying with his fifteen closest companions in the tiny church at Dives-sur-Mer. One of those companions was William de Warenne.

Meanwhile, Harald Hardrada had joined forces with the English king’s rebellious brother, Tostig, and landed an army in Yorkshire. King Harold marched with his army from London to repel the invaders. Although his soldiers were wearied after their long march, they attacked the enemy and – after a bitter and bloody battle – emerged victorious on 24th September. Both Harald Hardrada and Tostig were killed.

On 28th September, William and his knights landed in Pevensey, Kent.

On 1st October, King Harold and his exhausted soldiers marched three hundred kilometres back to the south of England. The two forces met at Battle, near Hastings, on October 14th.

At first, the Saxon two-handed axes carved through the chainmail of the Norman knights. On the second day of the battle, though, Harold was shot through the eye by an arrow (or so the story goes). His death disheartened the English forces, and soon the battle was won by the invading Normans.

On Christmas Day 1066, Duke William of Normandy was crowned King of England.

William de Warenne was one of the knights who fought at the Battle of Hastings, and he was rewarded richly for his courage and loyalty.

Almost immediately, he married Gundred, one of Queen Matilda’s ladies-in-waiting. Her tombstone at St. John's Church, Southover, Lewes, reads: ‘Within this Pew stands the tombstone of Gundrad, daughter of William the Conqueror, and wife of William, the First Earl of Warren.’

Much as I’d love to say that I was descended from William the Conqueror himself, there is no historical record of her birth and so most genealogists today think this claim is untrue. However, another branch of our family tree leads straight back to the Conqueror’s sister, Adelaide, which makes feisty Herleva the tanner’s daughter my great-grandmother-times-sixteen, a connection I’m proud to claim.

The Domesday book of 1086 shows that William de Warenne’s lands stretched over thirteen counties, from Conisbrough in Yorkshire to Lewes in Sussex, making him one of the richest men in the kingdom. In 1088, he was named the first Earl of Surrey. He did not, however, live to enjoy his earldom, dying later the same year.

His son William de Warenne, the second earl of Surrey, met a young woman named Isabel de Vermandois at a tournament and eloped with her, even though she was already married to Robert de Beaumont, the earl of Leicester. She had been married to him at the age of eleven and had given him nine children. Her husband is said to have died at shame at her wantonness, and she married William de Warenne II soon afterwards.

The blood of kings ran in Isabel’s veins. Her father was Hugh Capet, younger son of King Henry I of France. Her mother was Adelaide de Vermandois, descended from Charlemagne himself.

Their son and heir, William, the third earl, was born in 1119. He died on Crusade in Turkey whilst fighting in the elite royal guard of King Louis VII of France. His only child, a daughter, also named Isabel, became the greatest heiress in England. She too married brilliantly, with her second husband being Hamelin, the nephew of Henry II.

Isabel and Hamelin’s grand-daughter – also named Isabel – is known to history as the countess who chastised the king. In 1252, the king took one of her properties and granted it to one of his favourites. She confronted the king, asking: ‘Where are the liberties of England, so often recorded, so often granted, and so often ransomed?’

Henry III responded derisively, ‘curling his nostrils’, and asked who had given her permission to speak. Isabel argued that the king had given her the right to speak in the articles granted in Magna Carta, and accused the king of being a ‘shameless transgressor’. The king dismissed her angrily, but Isabel continued to fight for her rights through the courts.

Eventually the king wrote: ‘Henry, by the grace of God king of England … duke of Normandy and Aquitaine and count of Anjou sends greetings … Know that we have pardoned our beloved and faithful Isabella countess of Arundel ... by our seal of England, provided she says nothing opprobrious to us as she did when we were at Westminster.’

This spirit of independence and unwillingness to bow to authority saw the loss of the earldom a few generations later.

John de Warenne, the seventh earl, had inherited the title from his grandfather after his father died fighting in a tournament. He was married at the age of twenty to Joan of Bar, the ten-year old granddaughter of Edward I. However, John was in love with another woman, Maud of Nerford, the daughter of a Norfolk gentleman. Even when threatened with excommunication, John would not abandon his mistress. He tried to have his marriage to Joan annulled in 1314, both on the grounds of consanguinity (they were closely related by blood) and unwillingness.

A long legal battle followed. John was living openly with Maud, and they had several children together. The Countess Joan was living alone in the Tower of London at the king’s expense. In the end, though, the annulment was denied and John was excommunicated. The British Museum holds the registers of the archbishop of Canterbury which condemned ‘the brave and noble earl … for keeping Dame Mawd de Nereforde against the law of God and the order of the holy church, putting from him his deare wife.’

By the 1340s, both Maud Nerford and her sons had died, but John de Warenne had a new mistress named Isabella Holland. Once again he attempted to divorce Joan so that he could marry his mistress and legitimise their children. He was refused, however, and he died soon afterwards, in 1347, at the age of 61. Without a legitimate heir, the earldom was inherited by his sister’s son, the tenth Earl of Arundel. John de Warenne’s numerous illegitimate children were left with little more than a purse of coins each (though one of his sons, William de Warenne, also inherited a silver gilt helmet and armour).

The year after John de Warenne died, the Black Death was carried to England by fleas burrowing in the fur of rats. Millions of people died as a result, and parish records were left in chaos. This means there are a few gaps in the historical record.

A William de Warynge was noted in Staffordshire’s court rolls in 1386, after being caught fishing in a neighbour’s fishponds in Wyghtwyck (now called Wightwick), about four miles from Wolverhampton.

In 1419, a man named Nicholas Waring was included by the Sheriff of Staffordshire in a list of eligible knights ‘bearing arms from their ancestors for the service of the king in defence of the realm.’ He is believed to be the son of William Waring of Wolverhampton, a prosperous wool merchant.

Nicholas’s descendants were known as the Warings of the Lea, after their moated manor house in Wolverhampton. Our ancestor Charlotte Waring is directly descended from this branch of the family.

She certainly believed that she was descended from the first William de Warenne, the Norman knight who became the first Earl of Surrey. It is what she told her own children. Her eldest daughter Charlotte Elizabeth repeated it to her children, who passed it down through six generations to Binny and me. And her youngest daughter, my great-great-great-great-aunt Louisa, wrote it down for her own child, almost as if she knew she would never live to see her daughter grow up.

The only way to prove it for sure would be to do a DNA test on the crumbling bones of the first earl. He was buried at Lewes Priory in Sussex more than nine hundred and thirty years ago. The priory was destroyed by Henry VIII in the 1530s, and the graves of William de Warenne and his wife Gundred were thought lost. In 1845, however, a railway line was dug straight through the ruins of the priory and workmen dug up two small lead caskets containing human bones. They were reburied in a small Norman-style chapel built at St John the Baptist church in Southover, Lewes.

Somehow I do not think the church would approve of me asking for an exhumation!

I would have loved to have found that missing link from the 14th century that proved that the oral story we all inherited was true: that Charlotte Waring, the intrepid young governess who built a life for herself in Australia, was indeed related to that intrepid young Norman knight who fought at the Conqueror’s side almost a thousand years ago.

I spent many hours trying to find the connection. Once or twice my heart leapt as I found a mention in an antique book of pedigrees or a genealogical website, but always there was as much evidence to contradict the link as to prove it. The Wolverhampton Antiquarian, for example, published in 1933, says: ‘the family appears to be of very ancient origin. It is probably connected with … one Warine de Penne …’ (Penn is a parish of Wolverhampton, not far from where the Lea once stood).

And Ronald Waring, the 18th Duke of Valderano, wrote in response to a querying letter from Jan Gow, our second cousin: ‘I had always believed that the Warings of the Lea were descended from the third son of the third duke … (though) it is very possible that the Warings of Owlbury (and) the Lea are descended from us … from about 1335.’

So I did what any self-respecting amateur genealogist does these days – I spat into a tiny test-tube and sent it off to Ancestry.com. It came back with the most predictable results possible! The epicentre of my ethnicity is very firmly centred on southern-eastern England and north-western France i.e. Kent, Surrey, Sussex and Normandy!

When I began my investigation into the origins of the de Warenne family, I knew – from the family tree we all inherited – that my family was descended in one way or another from kings and tyrants.

I did not want to prove I was descended from William the Conqueror, or Charlemagne. After all, as Richard Dawkins has said, all living creatures are cousins. Go far enough back, and we humans are related to both orangutans and octopuses.

What I wanted was to discover was the stories behind the names and the dates. Tales of life and death, love and war, victory and defeat, happiness and heartbreak. It is these stories that connect us across the divide of a thousand years, and make us aware of our common humanity. Stories of our past shape our psyche.

What I most wished for was some kind of sign that my family’s irresistible compulsion to write had deep roots in the past. I have always wanted to be a writer. I say I was born knowing it was my one true destiny (and although I say it light-heartedly, I am not joking). I began scribbling stories and poems as soon as I could hold a pencil, and wrote my first novel – longhand in an old school exercise book – when I was only seven. By the time I had finished school, I had written half-a-dozen novels and innumerable poems and stories. My sister Binny and my brother Nick are the same. Between the three of us, we have published almost 90 books.

Where does it come from, this insatiable urge to write? Surely it is a part of us, like my dark hair and pale skin, like Binny and Nick’s chocolate-brown eyes. Surely it has been passed down to us, a chain link in the miraculous double-stranded spiral of our DNA.

‘I’m hoping for troubadours,’ I joke. ‘Surely somewhere in our ancestry is a wandering minstrel with a penchant for writing love poetry?’

So you can imagine how happy I was to discover that, in the twelfth century, a man named Aymon de Varennes wrote a long poem of adventure, magic and romance entitled Le Roman de Florimont. It tells the story of a brave young hero who confronts the giant Garganeus, marries the beautiful princess Romandaaple, and frees her father, the king, from prison. It was one of the most popular romances of the medieval period.

Aymon de Varennes’s ancestry is unknown, and it is impossible to say with any certainty that he was descended from the same stock as my ancestor, William de Warenne.

But I like to think he was.

The Blurb (from Goodreads):

When Anne Morrow, a shy college senior with hidden literary aspirations, travels to Mexico City to spend Christmas with her family, she meets Colonel Charles Lindbergh, fresh off his celebrated 1927 solo flight across the Atlantic. Enthralled by Charles’s assurance and fame, Anne is certain the aviator has scarcely noticed her. But she is wrong. Charles sees in Anne a kindred spirit, a fellow adventurer, and her world will be changed forever. The two marry in a headline-making wedding. In the years that follow, Anne becomes the first licensed female glider pilot in the United States. But despite this and other major achievements, she is viewed merely as the aviator’s wife. The fairy-tale life she once longed for will bring heartbreak and hardships, ultimately pushing her to reconcile her need for love and her desire for independence, and to embrace, at last, life’s infinite possibilities for change and happiness.

What I Thought:

The Lindberghs were incredibly famous in their day, both for their feats of flying, and for the kidnap and murder of their first child. This beautifully written novel reimagines the life of Anne Morrow Lindbergh from the time of her first encounter with the handsome but controlling aviator Charles Lindbergh to his death. It deals with his infatuation with the Nazis, the terrible months following their boy’s kidnap, and the writing of Anne’s own book, ‘Gift from the Sea’, which I remember reading as a teenager.

Not being American, I did not know much about the Lindbergs except their name and the fact their first child was kidnapped and murdered. I found this novel really fascinating as it draws in so much about the period. I came to realise just how extraordinary their feats of flying were, and how extraordinary it was for Anne to write ‘Gifts from the Sea’, a book of such beauty and grace, after suffering such a horrible tragedy.

The book is deftly written and a real page-turner – I devoured it in several sittings. It reminded me of Nancy Horan’s books Loving Frank and Under A Wide, Starry Sky in that it is a book about a woman who has lived her life in the shadow of a man but whose own story is just as compelling

The Aviator’s Wife is a really moving and powerful novel about one woman’s extraordinary life – I strongly recommend it.

You might also like to read my review of The Paying Guests by Sarah Waters:

VINTAGE BOOK REVIEW: The Paying Guests by Sarah Waters

The Blurb (from Goodreads):

In the spring of 1942, young Elzbieta Rabinek is aware of the swiftly growing discord just beyond the courtyard of her comfortable Warsaw home. She has no fondness for the Germans who patrol her streets and impose their curfews, but has never given much thought to what goes on behind the walls that contain her Jewish neighbors. She knows all too well about German brutality--and that it's the reason she must conceal her true identity. But in befriending Sara, a nurse who shares her apartment floor, Elzbieta makes a discovery that propels her into a dangerous world of deception and heroism.

Using Sara's credentials to smuggle children out of the ghetto brings Elzbieta face-to-face with the reality of the war behind its walls, and to the plight of the Gorka family, who must make the impossible decision to give up their newborn daughter or watch her starve. For Roman Gorka, this final injustice stirs him to rebellion with a zeal not even his newfound love for Elzbieta can suppress. But his recklessness brings unwanted attention to Sara's cause, unwittingly putting Elzbieta and her family in harm's way until one violent act threatens to destroy their chance at freedom forever.

From Nazi occupation to the threat of a communist regime, The Warsaw Orphan is the unforgettable story of Elzbieta and Roman's perilous attempt to reclaim the love and life they once knew.

My Thoughts:

I’m a big fan of Kelly Rimmer – she has a warm, intimate writing style that just flows beautifully. This book is set in Warsaw during the war years, a time and place I have always been interested in (I have actually written a story that draws upon the same setting, called ‘The Blessing’, which was published in The Silver Well, a collection of stories co-written with Kim Wilkins). The narrative is told from two first-person points-of-view. The first is Roman Gorka, a Jewish teenager locked up in the Warsaw ghetto with his family. The second is Elzbieta Rabinek, a girl who wonders sometimes what lies beyond the high walls of the ghetto. When she makes friends with her neighbour, a nurse who works secretly to save children from the ghetto, she is drawn into the dangerous world of the underworld resistance to the Nazi occupiers. The story follows their struggles to survive, the forced evacuations, the famous ghetto uprising, the later battle to liberate Warsaw from the German occupation and the infamous Soviet invasion. It’s a heart-rending struggle, and brought me to tears more than once. What I loved most about The Warsaw Orphan is how real it was – the story of two young people struggling to survive in a world gone mad, fighting hate, injustice and tyranny, and their own conflicted emotions, trying to discover how to build a life in the ashes of a terrible war. A truly beautiful book.

You might also like to read my review of The Dollmaker of Krakow by R.M. Romero:

https://kateforsyth.com.au/what-katie-read/book-review-the-dollmaker-of-krakow-by-r-m-romero

I used to love reading time travel adventures when I was a child. They were one of my favourite genres of fiction, and I’ve always wanted to write one.

When I first began daydreaming about the story that would become ‘The Puzzle Ring’, it seemed to me to be the perfect opportunity to finally write that time travel story. As part of my research into writing the book, I went back and revisited some of my favourite time travel books, interested by how they managed the slippage back in time, and articulating some of the difficulties a contemporary child would have in what is essentially a foreign world.

Here is a list of my favourite time travel books for those of you who want to go on and read more ...

1906 - Rudyard Kipling, Puck of Pook's Hill

I loved this book when I was about 11, reading it over and over while I was on holiday at my great-aunt’s one year. My nickname was Puck for a long time afterwards. It is about a brother and sister who met the mischievous Puck of Pook’s Hill, and he magically transports them into different periods of English history. At one point I thought of structuring ‘The Puzzle Ring’ in the same way, but in the end I decided to choose just one favourite period of history – the last winter in the tragic reign of Mary, Queen of Scots ...

And Rudyard Kipling’s advice to people who want to write: “Gardens are not made by singing "Oh, how beautiful," and sitting in the shade.”

1906 - Edith Nesbit, The Story of the Amulet

This is the last book in the series that begins with Five Children and It (which was made into a movie a few years ago). ‘The Story of the Amulet’ tells of the adventures of the five children as they go back in time to various places like Ancient Egypt, and Atlantis just before it floods. They even go forward in time to a wonderful utopian future. I loved these books, and particularly liked the way each of the characters seemed like real people.

1908 - Edith Nesbit, The House of Arden

‘The House of Arden’ has always been my favourite Nesbit novel. It’s about a boy who inherits a crumbling old castle when he is close to his tenth birthday but to his consternation he will only be able to keep it if he can find the lost Arden fortune before his birthday. He and his twin sister and a magical talking creature travel through time searching for the treasure. Like the previous books, they visit many different periods, and it’s tremendously exciting, with lots of encounters with highwaymen and the like. This book was definitely a very strong influence on me, particularly when I first began to conceive the story of ‘The Puzzle Ring’.

1939 - Alison Uttley, A Traveller In Time

Another favourite book from my childhood, this book tells the story of Penelope, who slips back and forth between her own time (1930s England) and Elizabethan times. This novel was one of the things which first began my fascination with Mary, Queen of Scots, because in this novel the house, Thackers, is owned by the Babington family, who famously tried and failed to rescue the Scottish queen while she was imprisoned by her cousin, Elizabeth I.

1954 - Lucy Boston, The Children of Green Knowe

Not many people have read Lucy Boston anymore which I think is such a shame. I loved this book as a child, and loved it just as much when I read it again while writing ‘The Puzzle Ring’. It’s very different from the other books, being quieter and more reflective, and young hero Tolly never actually goes back in time. Instead, his great- grandmother Mrs Oldknowe tells him vivid, exciting stories about the past which seem to imbue the house with the spirits of the past. There is a sense of the past being always with us, and the house and garden itself worked itself deep into my imagination. It was based on Lucy Boston’s own house, The Manor, in Hemingford Grey, Cambridgeshire, which was built in the 1130s and lays claim to the oldest continually inhabited house in the UK. Part of me still longs to live in a house filled with ghosts of the past. The BBC made a TV series based on the book.Lucy Boston once wrote: “I believe children, even the youngest, love good language, and that they see, feel, understand and communicate more, not less, than grownups. Therefore I never write down to them, but try to evoke that new brilliant awareness that is the world.’

This is what I try and do too.

1958 - Philippa Pearce, Tom's Midnight Garden

‘Tom’s Midnight Garden’ won the Carnegie Medal in 1958, and is considered one of the great classics of English children’s literature. I think it is utterly enchanting, and perfect in every way. It’s one of those books that stay with you forever after.

Tom is sent to stay with his aunt and uncle in a boarding house when his brother gets measles. Bored to tears, he has nothing to do and wishes the old house had a garden in which he could play. That night he hears the old grandfather clock in the hallway downstairs strike thirteen, and runs downstairs to investigate. He finds the hallway opening on to the most wonderful garden, and explores it in absolute delight. Soon he meets a girl called Hattie, who he discovers lived there in the 19th century. She thinks Tom is a ghost, while he thinks she is – they argue about it and it makes Tom uneasy. As the days pass, Hattie grows up while Tom stays the same. The time comes for Tom to go home, but he doesn’t want to go – the midnight garden as become more real, more important to him than his real life. The ending is one of the most perfectly executed and moving moments in children’s literature – I feel the catch of breath, the sting of tears, every time I read it.

An amusing anecdote: when Philippa Pierce went to Buckingham Palace to collect her OBE, the Queen asked her, ‘Where do you get your ideas from?’ To which, Phillipa Pierce replied ‘Harrods.’ I just love that.

1966 - William Mayne, Earthfasts

I did not read this book as a child, but bought it over the internet while I was writing ‘The Puzzle Ring’ as it has been called a classic time travel adventure. Its quite different from any of the books above. It is set in contemporary times (well, in the late 1960s anyway), and tells the story of two boys who hear drumming under the hill and set out to investigate. Then a boy from the 18th century unexpectedly marches out of the from under the hill and out of his own time. The boys try and help him to go back, but this has all sorts of strange and spooky consequences. One of the boys discovers the candle the drummer boy was carrying gives off cold rather than heat, and does not burn down. Strange things begin to happen – all the pigs disappear and instead wild boar rampage through the town. Standing stones walk. Slowly we come to realise that a king and his knights sleep under the hill and the drummer boy has woken them too soon – and trying to reverse this mistake may well cost the boys their lives. Many of what happens is never explained, so the book retains a sense of mystery and creeping suspense which is very effective. It’s been turned into a BBC series too.

1976 - Penelope Lively, A Stitch in Time

Maria, a quiet, lonely child who loves to read and daydream goes down to stay at the seaside in a big, old house still fill with furniture from its former owners. Maria begins to imagine she can see and hear the ghost of a child who used to live there and who sewed but never finished an old sampler that hangs in the playroom. She thinks a lot about time and how it haunts us, and grows obsessed with finding out more about Harriet who she fears must have died tragically. For a time, Maria is emotionally drawn back into the past but a new friendship with the boy next door helps her look forward to the difficult transition to adulthood. It’s a lovely book, slight, simple and haunting, and reminds us just how powerful the imagination of a child can be.

1978 - Jill Paton Walsh, A Chance Child

This is another classic that I read as an adult. It is much darker and more confronting than most of the books I loved as a child. At times it is quite harrowing. It tells the story of Creep, a boy who flees abuse at home, and somehow finds himself back in the time of the Industrial Revolution. It examines child labour, which was essentially child slavery, and brought me to tears. Although it has none of the magic and wonder and adventure that I love so much about children’s literature, its depiction of the past was real and true, and showed me not to be afraid of trying to make my past as authentic as possible.

1988 - Jane Yolen ‘The Devil’s Arithmetic’

A beautiful and moving novel about the Holocaust, The Devil’s Arithmetic tells the story of Hannah who, embarrassed by her grandparents’ enduring grief over their past, finds herself transported back to a village in Poland in the 1940s. Captured by the Nazis, she is taken to a death camp where she fights to stay alive and retain her dignity. At the end, she chooses to go to the gas chamber to save a friend in a scene that had me sobbing out loud with horror and disbelief. At that moment she returns to herself in contemporary times, but with a much deeper understanding of her grandparents’ inability to shake off the past. This is truly a brilliant book, one that should be read by everyone. It has been made into a movie which I haven’t yet seen (though I would like to!)

1999 - Susan Cooper, King of Shadows

Nat Field is an American boy who uses acting as a way to escape his unhappy life. He flies to London to take part in a production of A Midsummer’s Night’s Dream at a rebuilt Globe Theatre. Somehow he finds himself waking up in 1599 in the body of another Nat, one who is to play Puck in the first ever production of Shakespeare’s play. Shakespeare himself appears and takes Nat under his wing, but Nat has to wonder how he will ever get back to his own time again.

I’m a big fan of Susan Cooper’s work and read everything she writes, so I really enjoyed this book.

I loved writing ‘The Puzzle Ring’ and I am now daydreaming about writing more time travel stories. One of their strengths is that you haave a contemporary child, with modern manners and sensibilities, thrown into the past and so having to deal with how very different things were back then.

For example, children were better seen but not heard; people had their tongues nailed to the pillory for speaking their minds; women were burnt to death for killing their abusive husbands; snails were boiled to make a tea to cure a fever; left-handed people were accused of being devil-worshippers.

Sometimes, when writing an historical novel, it is difficult to bridge the gap between the beliefs and customs of children four hundred years ago and now. Having a child of today go back in the past helps ease the imaginative leap the child has to make

The Blurb (from Goodreads):

Helen Lowe reimagines the Sleeping Beauty story from the point of view of the prince who is destined to wake the enchanted princess in this lush, romantic fantasy-adventure.

Prince Sigismund has grown up hearing fantastical stories about enchantments and faie spells, basilisks and dragons, knights-errant and heroic quests. He'd love for them to be true ”he's been sheltered in a country castle for most of his life and longs for adventure” but they are just stories. Or are they?

From the day that a mysterious lady in a fine carriage speaks to him through the castle gates, Sigismund's world starts to shift. He begins to dream of a girl wrapped, trapped, in thorns. He dreams of a palace, utterly still, waiting. He dreams of a man in red armor, riding a red horse—and then suddenly that man arrives at the castle!

Sigismund is about to learn that sometimes dreams are true, that the world is both more magical and more dangerous than he imagined, and that the heroic quest he imagined for himself as a boy . . . begins now.

My Thoughts:

New Zealand writer Helen Lowe reimagines the Sleeping Beauty story from the point of view of the prince in this beautiful, romantic fantasy for young adults. Prince Sigismund has grown up in a castle whose gardens and parklands are surrounded by a deep, tangled forest. He is kept locked away from the world, and so longs for adventures like the ones in the stories he loves so much – fantastical tales of knights-errant and heroic quests, faie enchantments and shape-shifting dragons.

One day a beautiful and mysterious lady in a fine carriage speaks to him through the castle gates, and Sigismund's world begins to change. He dreams of a raggedy girl trapped in thorns, and a castle that lies sleeping … soon he is caught up in an adventure as perilous and strange as that of any story he had ever heard …

I absolutely adored this book! I love fairy tale retellings, especially ones that are full of magic, peril, and romance, and ‘Thornspell’ is one of the best I’ve ever read. It reminded me of Robin McKinley’s early books, which are still among my favourite fairy tale retellings. ‘Thornspell’ very deservedly won the Sir Julius Vogel Award for Best YA Novel – it’s a must red for anyone who loves fairy-tale-inspired YA fantasy.

You might also like to read my review of Cuckoo Song by Frances Hardinge:

https://kateforsyth.com.au/what-katie-read/book-review-cuckoo-song-by-frances-hardinge

The Blurb (from Goodreads):

They don't know what I did. And I intend to keep it that way.

How far would you go to win? Hyper-competitive people, mind games and a dangerous natural environment combine to make the must-read thriller of the year. Fans of Lucy Foley and Lisa Jewell will be gripped by spectacular debut novel Shiver.

When Milla is invited to a reunion in the French Alps resort that saw the peak of her snowboarding career, she drops everything to go. While she would rather forget the events of that winter, the invitation comes from Curtis, the one person she can't seem to let go.

The five friends haven't seen each other for ten years, since the disappearance of the beautiful and enigmatic Saskia. But when an icebreaker game turns menacing, they realise they don't know who has really gathered them there and how far they will go to find the truth.

In a deserted lodge high up a mountain, the secrets of the past are about to come to light.

My Thoughts:

I’m reading a lot of murder mysteries right now, and this was recommended to me by Dervla McTiernan who is one of my favourite contemporary crime novelists. Shiver is set at a ski resort high in the French Alps, during the low season when the resort is shut. A group of old friends come together for a reunion – ten years ago, they were young snowboarders at the resort, training to make it big in the competitive world of professional snow sports. One of them disappeared, breaking the group apart, but now a mysterious invitation has drawn them back together – but not to rekindle friendships, as expected, but for ice-cold revenge.

The story is told from the first-person point-of-view of an unreliable narrator – a device beloved of modern crime writers - and the narrative alternates between the revenge drama of today and the bitter rivalry and jealousies of that winter ten years earlier. The author, Allie Reynolds, has a background in professional freestyle snowboarding, and this inside knowledge helps make the world of the characters feel real. I’m not a snowboarder myself (though my husband and children are), but thankfully Allie keeps the vernacular light and easy to understand. The narrator Milla is tough yet vulnerable, and the story whips along at a cracking pace from the very first line: ‘it’s that time of year again. The time the glacier gives up bodies.’ The atmosphere is suitably icy and terrifying, and Milla’s voice is pitch perfect. I whizzed through the book at high speed, and enjoyed it immensely. It does not read like a thriller written by a debut author at all!

You might also like to read my review of The Good Turn by Dervla Mctiernan:

https://kateforsyth.com.au/what-katie-read/book-review-the-good-turn-by-dervla-mctiernan

The Blurb (from Goodreads):

Upon the death of Mary I (Bloody Mary), Elizabeth I takes the throne and Brendan Prescott is called to aid the young queen amid a realm plunged into chaos and a court rife with conspiracy

London, 1558. Queen Mary is dead, and 25-year old Elizabeth ascends the throne. Summoned to court from exile abroad, Elizabeth’s intimate spy, Brendan Prescott, is reunited with the young queen, as well as his beloved Kate, scheming William Cecil, and arch-rival, Robert Dudley. A poison attempt on Elizabeth soon overshadows her coronation, but before Brendan can investigate, Elizabeth summons him in private to dispatch him on a far more confidential mission: to find her favored lady in waiting, Lady Parry, who has disappeared during a visit to her family manor in Yorkshire.

Upon his arrival at the desolate sea-side manor where Lady Parry was last seen, he encounters a strange, impoverished family beset by grief, as well as mounting evidence that they hide a secret from him. The mystery surrounding Lady Parry deepens as Brendan begins to realize there is far more going on at the manor than meets the eye, but the closer he gets to the heart of the mystery in Vaughn Hall, the more he learns that in his zeal to uncover the truth, he could be precipitating Elizabeth’s destruction.

From the intrigue-laden passages of Whitehall to a foreboding Catholic manor and the deadly underworld of London, Brendan must race against time to unravel a vendetta that will strike at the very core of his world—a vendetta that could expose a buried past and betray everything he has fought for, including his loyalty to his queen.

My Thoughts:

I’ve enjoyed this book hugely, as I’ve enjoyed every book in Christopher Gortner’s Spymaster series. He has a beautiful, easy writing style and each book is a fast-paced, action-packed, rollercoaster ride that still manages to bring the world of Elizabethan London roaring to life. The characters are absolutely spot-on, and the historical background is leavened into the dough of the story with a light, sure touch. The young Queen Elizabeth is made human in these books – an intelligent yet vulnerable woman who must fight to survive and rule. I also love the characterisation of the story’s protagonist, the illegitimate Brendan Prescott who is torn between love and duty in a way that rings very true. I’m hoping that Christopher will write many more books in this series – as long as he writes them, I will buy them.

You might also like to read my review of The Tenant of Wildfell Hall by Anne Bronte:

https://kateforsyth.com.au/what-katie-read/book-reviewthe-tenant-of-wildfell-hall-by-anne-bronte

The Blurb (from Goodreads):

The powerful Murrumbidgee River surges through town leaving death and destruction in its wake. It is a stark reminder that while the river can give life, it can just as easily take it away.

Wagadhaany is one of the lucky ones. She survives. But is her life now better than the fate she escaped? Forced to move away from her miyagan, she walks through each day with no trace of dance in her step, her broken heart forever calling her back home to Gundagai.

When she meets Wiradyuri stockman Yindyamarra, Wagadhaany’s heart slowly begins to heal. But still, she dreams of a better life, away from the degradation of being owned. She longs to set out along the river of her ancestors, in search of lost family and country. Can she find the courage to defy the White man’s law? And if she does, will it bring hope ... or heartache?

My Thoughts:

Anita Heiss’s new book is set along the banks of the Murrumbidgee River in the 1850s, and tells the story of a young Aboriginal woman named Waghadhaany (pronounced Wog-a-dine). The title means ‘River of Dreams’ in the Wiradjuri language of southern-central NSW - the river and its landscape and place in the lives of the local Indigenous people are central to this engrossing tale of love and loss, grief and gratitude, language and listening.

The story begins in 1838 when Waghadhaany is only a child, and her father warns a white settler not to build too close to the river, as it floods in the rains and becomes a powerful and dangerous force that sweeps away all in its path. The white man scoffs at him and takes no notice. Wagadhaany askes her father why she does not tell him that the river’s name, Marrambidya, means ‘big flood, big water’. He answers, ‘no matter what you say, or how many times you say it, ngamurr, some people, especially White people, they just won’t listen.’

Fourteen years later, the township of Gundagai was hit by a massive flood as the river broke its banks after a month of heavy rain. Almost one-third of the town’s population died in what was then Australia's worst flood disaster. Many of the survivors were rescued by the local indigenous people, including Wagadhaany’s father. The man he warned, however, dies.

The idea of listening is central to the novel. Wagadhaany must learn the language of her white employers, but they do not learn hers. They call her Wilma because they cannot be bothered to learn how to pronounce her name. Much of the wisdom of the Wiradjuri people is transmitted orally, through song and story. Yet Wagadhaany is taken away from her people and her country, and this loss wounds her. She is kept silent.

In one scene, she visits another camp and realises: ‘she’s had no conversation since leaving Gundagai. No language, no stories, no dancing, no sharing. She wonders how she can still live without so much that is important to her. She looks around the circle where the women are weaving and knows they must all be listening, because no-one else is talking.’ To find herself once more among her own kind hits Wagadhaany hard: ‘These women could be her gunhi, her grandmother, aunties and cousins. These could be her miyagan. She remembers the words of her own gunhi the last time she saw her. You will always have miyagan around this country, your Wiradjuri country … the Ancestors will be with you wherever you walk.’

The simplicity and naivety of the language is a perfect expression of Wagadhaany’s voice. Although she uses many Wiradjuri words, their meaning is always clear in the context of the story, and Anita provides a glossary at the back of the book just in case. I really loved this use of the Wiradjuri language throughout the story – it's a paean to an ancient culture steeped in myth and song and storytelling.

The loss of language, the loss of country, is the force which drives Wagadhaany as she grows up, makes friends, falls in love, and becomes a mother. Eventually, this force compels her to break free of her servitude to her white employers and she walks home, following the snaking course of the river of dreams. The novel flows like the great Murrumbidgee River itself, with powerful undercurrents that sweep the reader along.

The book is written with great delicacy and compassion. Wagadhaany grows from a girl filled with bewilderment and grief at the disruption of her world to a young woman of certainty and strength. And not all the white settlers are callous and unjust. Wagadhaany makes friends with a young Quaker woman named Louisa who tries to listen and understand, though her attempts to help are sometimes tone-deaf. It's so incredible to hear the story of Australia's colonial past in the voice of an Indigenous woman. It really illuminated our past for me, and taught me so much about a way of life that has sadly been largely lost. I feel Bila Yarrudhanggalangdhuray is a book that all Australians should read, to try and understand why our colonial past still causes so much pain and grievance.

You might also like to read my review of Barbed Wire & Cherry Blossoms by Anita Heiss:

BOOK REVIEW: Barbed Wire & Cherry Blossoms by Anita Heiss

We all know that we inherit the colour of our eyes from our parents.

If you sneeze when you look at the sun, that too was passed down through your genes. So was your ability to curl your tongue, and when you are likely to notice that first grey hair.

One thing I have always wondered is whether my lifelong compulsion to write was encoded in my DNA. People often ask me, ‘when did you first decide you wanted to become an author?’

I always answer, ‘I was born wanting it.’

My sister Belinda Murrell is an author too. So is my brother. The three of us have published more than 90 books between us.

We are not the only writers in our family. There are poets, novelists, journalists, and biographers going back for generations. My sister and I have just spent the past two years researching and writing Searching for Charlotte, a biography of our great-great-great-great-grandmother, Charlotte Waring Atkinson, who in 1841 wrote the first children’s book published in Australia.

Her youngest daughter, Louisa Atkinson, was the first Australian-born female novelist. Other writers in the family include Robert Waring, a friend of Ben Johnson, who wrote ‘Effigies Amoris, or the Picture of Love Unveil’d’ in the mid-1600s; Anna Letitia Waring, 19th century poet and composer of hymns; and her father the Reverend Elijah Waring, who wrote Edward Williams: The Bard of Glamorgan in 1850.

Writing does seem to be in our blood.

There are, of course, many other families where ink seems to run in their veins. The Brontë sisters. The Grimm brothers. The Rossetti siblings. Mary Wollstonecraft and Mary Shelley. Alexandre Dumas, père and Alexandre Dumas, fils. Four generations of Waughs. The Sitwells. Kingsley Amis, and his son Martin. A.S. Byatt and Margaret Drabble. Stephen King, and his son Joe Hill.

Literary DNA seems to be remarkably potent.

So is there a writing gene?

The inheritability of creativity has always been difficult to study, simply because creativity is so difficult to define and measure. What is genuis? What is artistic talent? Is the compulsion to create enough, or must the work have some kind of worth? How does one measure that worth?

Some writers are enormously celebrated in their time, only to be forgotten a few generations later. Others find fame only after their deaths. Some write only one book, others dozens. Some are both loved and loathed, according to the taste of their readers.

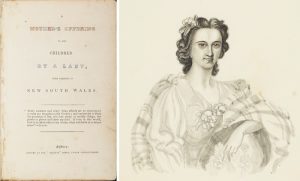

Our great-great-great-great-grandmother Charlotte Waring Atkinson falls into the ‘unjustly forgotten’ basket. Her book, A Mother’s Offering to Her Children, was published anonymously, By A Lady Long Resident in New South Wales. It was positively reviewed upon its publication, but now there are only a handful of first editions remaining, including one precious copy in the National Library of Australia. Her extraordinary life and achievements are hardly known beyond scholarly circles.

Yet her book was the first children’s book with an Australian setting, the first to draw upon Australian colonial history, the first to describe the lives of the Australia’s First Nation people. She also wrote poems and stories, was a fine visual artist, and a proto-feminist who fought for her right to live a self-determined life.

The fact that her daughter Louisa Atkinson was also a celebrated artist and author supports the idea that their creativity was passed down from mother to daughter. However, Charlotte also raised her and taught her all she knew.

It’s the age-old Nature v Nurture argument.

Recent studies into the inheritability of creative writing seem to show that it is indeed a trait that is passed down through the family. The most striking was led by Anna Vinkhuyzen, now Research Fellow at the Institute for Molecular Bioscience, University of Queensland. She and her team drew on data from the Netherlands Twin Register, which contains information on 1,800 identical twins and 1,600 non-identical twins. They found high levels of heritability (83%) for creative writing, which is much higher than for a broader category of arts such as painting (56%).

Other approaches have come up with similar results, showing that DNA does indeed play a strong role in creative writing. However, as Siddharta Mukherjee writes, in The Gene: An Intimate History, ‘it is nonsense to speak about “nature” or ‘nurture” in absolutes or abstracts ... the development of a feature or function depends, acutely, on the individual feature and the context.’

In other words, creativity is a constellation of fiery sparks ignited in a multitude of ways. The willingness to play, long hours of practice, dedication to one’s art, the desire and drive to create – all these matter too.

Nonetheless, it gives me great joy to know I am connected by a golden chain of DNA to my long-ago ancestor, who loved words and writing as much as I do.

Dr Kate Forsyth is a bestselling novelist, poet, and essayist. She has won many awards, including the 2015 American Library Association award for Best Historical Fiction for her novel Bitter Greens; the William Atheling Jr Award for Criticism for her doctoral exegesis, The Rebirth of Rapunzel: A Mythic Biography of the Maiden in the Tower; and a silver medal in the 2018 US Readers Favorite book awards for Vasilisa the Wise & Other Tales of Brave Young Women. Kate was recently awarded the prestigious Nancy Keesing Fellowship by the State Library of NSW to research and write a biography of her ancestor, Charlotte Waring Atkinson, the author of the first book for children published in Australia. Kate has a BA in literature, a MA in creative writing and a Doctorate of Creative Arts, and is also an accredited master storyteller with the Australian Guild of Storytellers.