The Blurb (from Goodreads):

In the story of the great lyric poet Simonides, Mary Renault brings alive a time in Greece when tyrants kept an unsteady rule and poetry, music, and royal patronage combined to produce a flowering of the arts.

Born into a stern farming family on the island of Keos, Simonides escapes his harsh childhood through a lucky apprenticeship with a renowned Ionian singer. As they travel through 5th century B.C. Greece, Simonides learns not only how to play the kithara and compose poetry, but also how to navigate the shifting alliances surrounding his rich patrons. He is witness to the Persian invasion of Ionia, to the decadent reign of the Samian pirate king Polykrates, and to the fall of the Pisistratids in the Athenian court. Along the way, he encounters artists, statesmen, athletes, thinkers, and lovers, including the likes of Pythagoras and Aischylos. Using the singer's unique perspective, Renault combines her vibrant imagination and her formidable knowledge of history to establish a sweeping, resilient vision of a golden century.

My Thoughts:

This year, I have been reading a lot of books set in Ancient Greece and particularly loved Mary Renault’s The King Must Die, Madeine Miller’s Circe and Pat Barker’s The Silence of the Girls. Widening my circle, I ordered another book by Mary Renault - The Praise Singer – because it had been recommended to me by a friend.

I enjoyed the book. It’s biographical fiction about a real-life poet named Simonides, who lived during the early classical period of Athens. We follow his journey from a wild and ugly boy, forced to work as a shepherd when all his soul yearns for music and poetry, to his life as an old man witnessing the end of the reign of the tyrant-king of Athens. Her writing is always vivid and vigorous, and the world of ancient Athens is well-drawn. I knew nothing about Simonides, or that particular period of history, and so I did find all the political machinations a bit of a drag. It meant the book did not have the narrative momentum of her Theseus books, and nor did it have the grandeur and mystery of the manifested presence of the old Greek gods in all their dreadful power.

Still, Mary Renault is a wonderful writer and so she manages to pull it off. I plan to read more of her work.

You might also like to read my review of The Bull from the Sea by Mary Renault:

https://kateforsyth.com.au/what-katie-read/book-review-the-bull-from-the-sea-by-mary-renault

The Blurb (from Goodreads):

In Hidden in Plain View, historian Jacqueline Tobin and scholar Raymond Dobard offer the first proof that certain quilt patterns, including a prominent one called the Charleston Code, were, in fact, essential tools for escape along the Underground Railroad.

In 1993, historian Jacqueline Tobin met African American quilter Ozella Williams amid piles of beautiful handmade quilts in the Old Market Building of Charleston, South Carolina. With the admonition to "write this down," Williams began to describe how slaves made coded quilts and used them to navigate their escape on the Underground Railroad. But just as quickly as she started, Williams stopped, informing Tobin that she would learn the rest when she was "ready."

During the three years it took for Williams's narrative to unfold--and as the friendship and trust between the two women grew--Tobin enlisted Raymond Dobard, Ph.D., an art history professor and well-known African American quilter, to help unravel the mystery.

Part adventure and part history, Hidden in Plain View traces the origin of the Charleston Code from Africa to the Carolinas, from the low-country island Gullah peoples to free blacks living in the cities of the North, and shows how three people from completely different backgrounds pieced together one amazing American story.

My Thoughts:

In 1993, historian Jacqueline Tobin met an elderly African American woman Ozella Williams selling her beautiful handmade quilts in a market in Charleston, South Carolina. They fell into conversation, and Ozella told Jacqueline that many of her designs had been passed down through her family and had once been used as a visual code to help slaves navigate their escape on the Underground Railroad. Jacqueline was intrigued but sceptical. How could quilts be maps? And, if Ozella’s story was true, why did nobody know about it? She questioned Ozella, but the old woman refused to tell her anymore. It was meant to be kept secret. When pressed, Ozella said she would tell Jacqueline the rest of the story when she was ‘ready’.

Jacqueline began to investigate the possibility that the story was true. She met with Ozella several times, the friendship and trust between them slowly growing, and she enlisted the help of Dr Raymond Dobard, an art history professor who specialised in African American quilts. They became convinced that the story had some premise in truth, and present the evidence they found to support Ozella’s story. The book was published in 1999, and has attracted controversy ever since. One of the problems is that which always arises when trying to prove oral history, which is by its nature slippery and unreliable – there is little empirical evidence to support the premise. Slave quilts were not preserved, nor their provenance recorded, nor their meaning questioned. Quilt patterns have different names and old ones are often adapted and renamed. Sadly Ozella Williams died soon after the book was completed, and so she cannot be questioned further.

I found the book absolutely fascinating. I am used to studying the way oral history and storytelling shapeshifts and camouflages itself, and I think that a lot of what the two authors have discovered is plausible. Here in Australia, we have the example of Indigenous storytelling where knowledge of country has been passed down word-of-mouth for thousands of years. One myth, from the Gunditjmara people of the south-east Australia, has been shown to carry evidence of a volcanic eruption that had occurred 37,000 years ago. And my sister and I, researching the life of our great-great-great-great-grandmother, found empirical evidence to prove numerous family stories that we had heard from our grandfather, who had heard them from his grandmother who had heard them from hers. To deny the value of oral history is to lose a rich fund of first-hand accounts of history, particularly in cultures where literacy was not the norm.

However, I do understand that many historians find the evidence debatable, and many non-historians wish the authors had just told the story of the quilts and their meaning, without the constant need to support their arguments. It’s the age-old tension between the historian and the storyteller. Read the book and decide for yourself.

You might also like to read my review of Threads of Life by Clare Hunter:

BOOK REVIEW: Threads of Life: A History of the World Through the Eye of a Needle by Clare Hunter

The Blurb (from Goodreads):

Everything has changed for Dr Ruth Galloway.

She has a new job, home and partner, and is no longer North Norfolk police's resident forensic archaeologist. That is, until convicted murderer Amyas March offers to make DCI Nelson a deal. Nelson was always sure that March killed more women than he was charged with. Now March confirms this, and offers to show Nelson where the other bodies are buried - but only if Ruth will do the digging.

Curious, but wary, Ruth agrees. March tells Ruth that he killed four more women and that their bodies are buried near a village bordering the fens, said to be haunted by the Lantern Men, mysterious figures holding lights that lure travellers to their deaths.

Is Amyas March himself a lantern man, luring Ruth back to Norfolk? What is his plan, and why is she so crucial to it? And are the killings really over?

My Thoughts:

This year I’ve been reading my way through the Ruth Galloway series of contemporary British crime novels by Elly Griffiths. The Lantern Men is the twelfth in the series, and just as readable and entertaining as the first. Dr Ruth Galloway is a forensic archaeologist, who began working with the Norfolk police way back in Book 1: The Crossing Places. Along the way she’s had an on-again-off-again affair with the lead detective, borne him a child, raised her daughter alone, and helped him solve a dozen intriguing murder cases. The joy of these books is the characters, who all seem so real, and the muddle they make of their personal affairs. Dr Ruth is clever, overweight, sceptical and determined to make it on her own. DCI Nelson is brusque, drives too fast, loves football and his family, and is prone to ordering people about. There is also the delightful Cadfael, one of Ruth’s best friends, a druid with a penchant for purple cloaks. That makes the books sound very charming and whimsical, which is true – but the mysteries are clever and hard-hitting, and the danger is very real. It’s a beguiling mix, which explains why so many people are as addicted as me. Start at the beginning, though! For the real joy is the developing relationships between the dramatis personae.

You might also like to read my review of The Dark Lake by Sarah Bailey:

https://kateforsyth.com.au/what-katie-read/vintage-book-review-the-dark-lake-by-sarah-bailey

The Blurb (from Goodreads):

A girl’s quest to find her father leads her to an extended family of magical fighting booksellers who police the mythical Old World of England when it intrudes on the modern world. From the bestselling master of teen fantasy, Garth Nix.

In a slightly alternate London in 1983, Susan Arkshaw is looking for her father, a man she has never met. Crime boss Frank Thringley might be able to help her, but Susan doesn’t get time to ask Frank any questions before he is turned to dust by the prick of a silver hatpin in the hands of the outrageously attractive Merlin.

Merlin is a young left-handed bookseller (one of the fighting ones), who with the right-handed booksellers (the intellectual ones), are an extended family of magical beings who police the mythic and legendary Old World when it intrudes on the modern world, in addition to running several bookshops.

Susan’s search for her father begins with her mother’s possibly misremembered or misspelt surnames, a reading room ticket, and a silver cigarette case engraved with something that might be a coat of arms.

Merlin has a quest of his own, to find the Old World entity who used ordinary criminals to kill his mother. As he and his sister, the right-handed bookseller Vivien, tread in the path of a botched or covered-up police investigation from years past, they find this quest strangely overlaps with Susan’s. Who or what was her father? Susan, Merlin, and Vivien must find out, as the Old World erupts dangerously into the New.

My Thoughts:

Garth Nix is one author whose books I always buy. And this is not just because he’s an old friend. He writes the very best kind of young adult fantasy – full of magic and adventure and old-fashioned storytelling, but with a very modern sensibility. And he’s always surprising. This new novel has a very intriguing premise. It’s set in 1983, a time I remember well, and centres on a young woman’s quest to find the father she has never known. Susan Arkshaw is tough and fiercely independent. She’s always had to look out for herself, for her father is unknown and her mother is strangely dreamy and vague, to the point of not really being quite there. She sets off to London to meet a man who once sent her mother a Christmas card, but before she can interrogate him he is turned to dust by the prick of a silver hatpin wielded by a left-handed bookseller named Merlin. Turns out he is one of an underworld of magical fighting detectives who conceal themselves behind the façade of bookshops, both dusty-and-cobwebby and brand-new. As Susan and Merlin are chased by hordes of different magical creatures, they team up to solve the mystery of just who Susan’s father might be, in a swiftly-paced, smart and funny romp through old English folklore. I just loved the premise, and am hoping this is the beginning of a whole new series.

You might also like to read my review of Angel Mage by Garth Nix:

BOOK REVIEW: Angel Mage by Garth Nix

The Blurb (from Goodreads):

Valentina Yershova's position in the Romanov's Imperial Russian Ballet is the only thing that keeps her from the clutches of poverty. With implacable determination, she has clawed her way through the ranks to soloist, utilising not only her talent, but her alliances with influential rich men that grants them her body, but never her heart. When Luka Zhirkov – the gifted son of a factory worker – joins the company, her passion for ballet and love is rekindled, putting at risk everything that she has built.

For Luka, being accepted into the company fulfills a lifelong dream. But in the eyes of his proletariat father, it makes him a traitor. As war tightens its grip and the country starves, Luka is increasingly burdened with guilt about their lavish lifestyles.

While Luka and Valentina's secret connection grows, the country rockets toward a revolution that will decide the fate of every dancer.

For the Imperial Russian Ballet has become the ultimate symbol of Romanov indulgence, and soon the lovers are forced to choose: their country, their art or each other...

My Thoughts:

I’ve always been fascinated by the Russian Revolution, and I’m a true balletomane, which means I love ballet. So this debut novel by Australian author Kerri Turner caught my attention from the outset, and was one of the first books I picked up when I was free to read solely for pleasure once more.

It’s set in Petrograd in 1914. Valentina has risen from grinding poverty to being one of the top dancers in the Imperial Russian Ballet, but the cost is very high – she is supported by rich patrons who can tire of her at any time and sell her on to some other man. Love, freedom, security – these are all impossible dreams. But Valentina lives to dance. Without the ballet, she has nothing. So she endures the degradation and humiliation of her life so that she can continue to dance, even while the opulent world of the Tsar and his family come under increasing pressure from revolutionary ideas.

Then a young man name Luka joins the company, and Valentina finds herself tempted not only by desire and the yearning for love, but the possibility of other ways to live, other ways to dance.

Yet to fall in love is to risk everything …

The Last Days of the Romanov Dancers is a compelling and beautifully written read, and I’m really looking forward to reading more by Kerri Turner. Her voice is deft and assured, her research impeccable.

You might also like to read my review of The Lace Weaver by Lauren Chater:

https://kateforsyth.com.au/what-katie-read/vintage-book-review-the-lace-weaver-by-lauren-chater

For the past three years, I have been working on a novel called The Crimson Thread, a reimagining of the Minotaur in the Labyrinth myth set in Crete during the Second World War.

I’ve been fascinated by the story of the minotaur ever since I read Tales of the Greek Heroes by Roger Lancelyn Green, when I was about fourteen. I found an old copy of the book shoved up in a top cupboard in my grandparents’ house one boiling hot summer when I was staying with them during the school holidays. In brief, the myth goes like this:

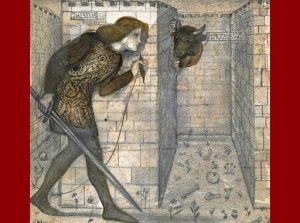

Every seven years, Athens had to send seven youths and seven maidens to Crete to be fed to the minotaur, a bull-headed man who was kept locked in a vast labyrinth. No-one had ever escaped. One year, Theseus, the prince of Athens, volunteered to go in the hope that he could kill the minotaur and so free his city from the sacrificial tribute. Once in Knossos, the Cretan princess Ariadne fell in love with Theseus, and offered to help guide him through the labyrinth. She gave him a ‘clue of thread’ and told him to fasten one end to the door of the labyrinth. Theseus then ‘traced his way through the winding passages, leading up and down, hither and thither, until he came to the great … cavern in the centre … where the monster (was) waiting for him.’

Edward Burne-Jones, ‘Theseus and the Minotaur’, ink and pen drawing (1861)

Theseus slaughters the minotaur and follows the thread out of the labyrinth, and then he and Ariadne flee Crete and her father’s wrath. But Theseus then betrays Ariadne and abandons her, and Dionysus, the god of wine and ecstasy and epiphany, falls in love with ‘her wild, dark beauty’ and weds her, making her immortal. Her crown of stars is flung up into the heavens, and becomes the Coronoa Borealis, a navigational aid to help those who are lost.

In the version I read as a child, Theseus does not abandon her willingly, but that is because - for Roger Lancelyn Green – Theseus is the hero and so should not behave so callously. Another detail that Green left out is that the minotaur is Ariadne’s half-brother.

I don’t know why this ancient myth struck me so forcibly. Perhaps because it was the only story in the book where a girl has an instrumental role to play. It is not the hero Theseus who solves the puzzle of how to escape from the labyrinth, it is Ariadne. He is simply doing her bidding.

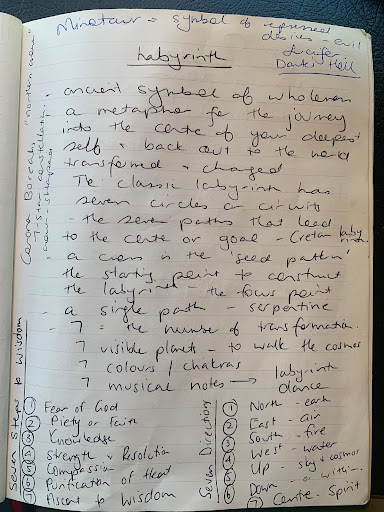

The minotaur in the labyrinth is a very old tale, older even than ancient Greece, because its roots lie in the bull-dancing culture of the Minoan civilisation that existed in Crete from around 2000 BCE. The ruined palace of Knossos – which is where my story is centred – has evidence of this in its frescoes and artefacts.

The Bull-Leaping Fresco, c. 1450 BC

Bull-leaper bronze figurine, c. 1600 BC

The Palace of Knossos was so famous as the source of the minotaur in the labyrinth myth, that the symbol is depicted on its ancient coins.

Silver tetradrachm, Knossos, Crete. 2nd-1st century BCE.

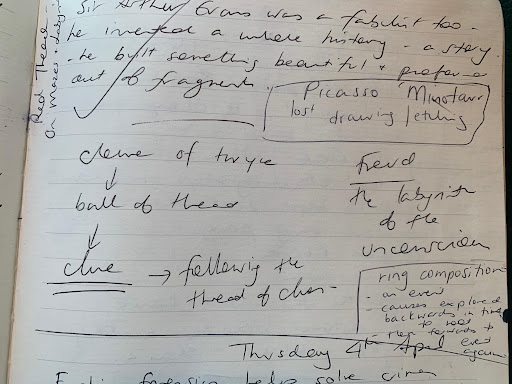

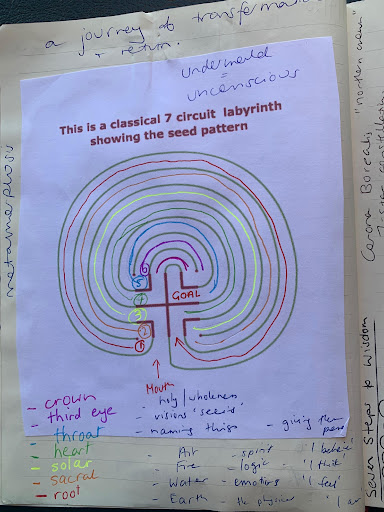

Both Freud and Jung were fascinated with the labyrinth as a symbol of the unconscious mind. In his book ‘Man and His Symbols’ (which I first read when I was sixteen), Jung wrote: ‘The maze of strange passages, chambers, and unlocked exits in the cellar recalls the old Egyptian representation of the underworld, which is a well-known symbol of the unconscious … It also shows how one is “open” to other influences in one’s unconscious shadow side and how uncanny … elements can break in.’

So when we walk the labyrinth we journey to that deep dark place hidden within us, and face our shadow side.

I have always found it so interesting that our word ‘monster’ comes from the Latin verb monere which means ‘to warn’ and the Latin noun monstrum which means ‘an evil omen’. Other words that come from the same root are ‘monitor’ (someone who warns), ‘admonition’ (to express disapproval), ‘premonition’ (a forewarning), demonstrate (to show or reveal) and remonstrate (to prove through argument or pleading) and – less obviously – ‘summon’, which originally meant to admonish or warn secretly.

Monsters have haunted the human imagination from the beginning of our history, manifesting our fears and desires and urges, particularly those we repress most deeply. They appear most commonly in stories – in our myths and legends and fables, our dramas and novels and films. This is because storytelling is the most effective tool we have to process the terrors of the night. Monsters give us a way to embody and examine these fears. Monsters are metaphors for thinking with.

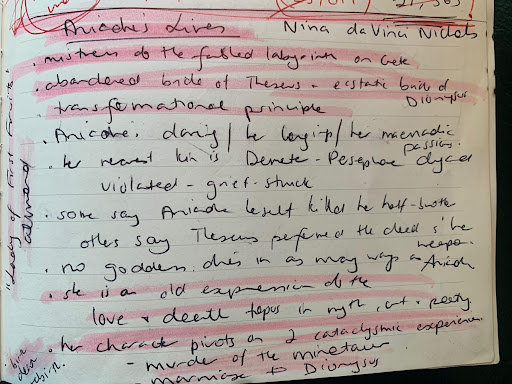

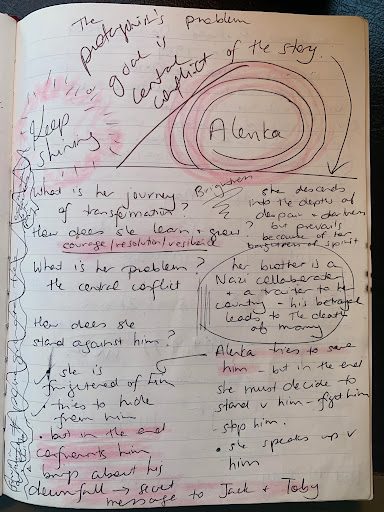

Here are a few pages from my notebook that show me working out some of my thoughts about minotaurs and labyrinths, and my protagonist’s own journey to the underworld and back.

The Crimson Thread will be released by Penguin Random House Australia in July 2022.

The Blurb (from Goodreads):

Sofka Zinovieff had fallen in love with Greece as a student, but little suspected that years later she would, return for good with an expatriate Greek husband and two young daughters. This book is a wonderfully fresh, funny, and inquiring account of her first year as an Athenian. The whole family have to come to grips with their new life and identities—the children start school and tackle a new language, and Sofka's husband, Vassilis, comes home after half a lifetime away. Meanwhile, Sofka resolves to get to know her new city and become a Greek citizen, which turns out to be a process of Byzantine complexity. As the months go by, Sofka's discovers how memories of Athens' past haunt its present in its music, poetry, and history. She also learns about the difficult art of catching a taxi, the importance of smoking, the unimportance of time-keeping, and how to get your Christmas piglet cooked at the bakers.

My Thoughts:

I’ve spent the past few years writing a book set in Crete during World War II. As part of my immersive research process, I have been reading as many books about Greece that I could lay my hands on. This book was recommended to me by a friend, and I enjoyed it hugely. Sofka Zinovieff married a Greek and moved with him to Athens with their two young daughters. She wants to learn as much about Greek culture, history and way of life as she can, even while despairing of some of the country’s eccentricities - the labyrinthine bureaucratic system, the peculiar hold that religion has on the every day, the lack of punctuality, and so on. She has an engaging writing style, a journalist’s eye for what makes a good story, and an anthropologist’s insight into culture and behaviour. And I always enjoy books about people who move to live somewhere different in the world. I can live vicariously through them!

You might also like to read my review of Ghost Empire by Richard Fidler:

https://kateforsyth.com.au/what-katie-read/vintage-book-review-ghost-empire-by-richard-fidler

The Blurb (from Goodreads):

In this sequel to The King Must Die Theseus defies the Gods’ and claims the throne of Athens a move that culminates in the terrible, fateful destruction of the house of Minos -- the Minotaur.

My Thoughts:

I read The King Must Die when I was a teenager, and it made a deep impression on me. It felt so vividly real and strange. I read it again last year, and when I posted my review, someone told me that I must go on and read its sequel, The Bull From the Sea. It’s taken me a while, but at last I picked it up off my shelf and settled down to read it. The two books chronicle the life of the ancient Greek hero, Theseus. The first covers his childhood and his journey to Crete to become a bull-leaper at the palace of Knossos, his affair with Ariadne, the killing of the Minotaur and his return to Athens. The second picks up from from this point:

It was dolphin weather when I sailed into Piraeus with my comrades of the Cretan bull ring. Knossos had fallen, which time out of mind had ruled the seas. The smoke of the burning Labyrinth still clung to our clothes and hair.

The book then follows Theseus through to his old age. The sweep is broad - years are covered in a few paragraphs at times - and so The Bull From the Sea does not have the intensity of focus of The King Must Die. Mary Renault has a gift for narrative drive, though, and so the pace of the book does not flag. Theseus is not altogether a sympathetic protagonist. He can be cruel and careless, and his temper is quick. His attitudes to women leave a lot to be desired as well, though it must be said it was a cruel and misogynist age, and Theseus’s’s attitudes ring true for the time.

Mary Renault is a really interesting writer, with a powerful gift for bringing the past to pulsing life. Her prose in particular is so muscular and vigorous, so full of freshness and vitality, I can only be in awe. I’m planning on reading more of her work.

You might also like to read my review of The King Must Die by Mary Renault:

https://kateforsyth.com.au/what-katie-read/book-review-the-king-must-die-by-mary-renault

The Blurb (from Goodreads):

In 1970s Argentina, mothers marched in headscarves embroidered with the names of their “disappeared” children. In Tudor, England, when Mary, Queen of Scots, was under house arrest, her needlework carried her messages to the outside world. From the political propaganda of the Bayeux Tapestry, World War I soldiers coping with PTSD, and the maps sewn by schoolgirls in the New World, to the AIDS quilt, Hmong story clothes, and pink pussyhats, women and men have used the language of sewing to make their voices heard, even in the most desperate of circumstances.

Threads of Life is a chronicle of identity, protest, memory, power, and politics told through the stories of needlework. Clare Hunter, master of the craft, threads her own narrative as she takes us over centuries and across continents—from medieval France to contemporary Mexico and the United States, and from a POW camp in Singapore to a family attic in Scotland—to celebrate the age-old, universal, and underexplored beauty and power of sewing. Threads of Life is an evocative and moving book about the need we have to tell our story.

My Thoughts:

This was such a fascinating read! It was full of thing that chimed with me – the story of the Bayeux tapestry (which I have written about several times on my blog) and Mary, Queen of Scots’ and her exquisite embroidery (she appears in my novel The Puzzle Ring), and embroidery written in secret codes (which I am writing about now) – and I learned so much along the way too. I love to sew (though I do it very badly), and I love the idea of sewing being a subversive art that allows people to express themselves and communicate their feelings in such a simple fundamental way. As Clare Hunter writes: You cut a length of tread, knot one end and the pull the other through the eye of a needle. You take a piece of fabric and push your needle into one side of the cloth and then pull it out on the other … You don’t need expensive tools, or years of training, or a university degree. You just need hands.

You don’t need to love sewing to enjoy this book (though it may make you want to try y0ur hand at it). Because Threads of Life simply takes the history of sewing as a lens to look at human history, with a particular emphasis on sewing as a means of self-expression for the hurt, the maimed, the marginalised, and the powerless. Most (but not all) are women. My only quibble – I would have loved an illustrated copy! But I searched up images on the net as I read, and I loved that as well. A really beautiful, thoughtful book.

You might also like to read my review of A Library: A Catalogue of Wonders by Stuart Kells:

https://kateforsyth.com.au/what-katie-read/book-review-the-library-a-catalogue-of-wonders-by-stuart-kells