I have a secret page on my website that only those that search carefully can find. I call it The 50/50 Project ...

It is a list of all my hopes and dreams - both possible and impossible - & all the places I hope to one day go and all the things I hope to one day do. I call it The 50/50 Project because it was inspired by the inching closer of my 50th birthday and the realisation that there are still so many things in the world I want to do (I found 50 of them, hence the title). The idea is that - as I go somewhere or achieve something - I'll blog about it, and gradually be able to cross off some of these dreams.

Today I am crossing off:

No 49: Win A Major Literary Prize

I have been short-listed for lots of awards and won a few.

‘The Puzzle Ring’ was short-listed for the 2009 Aurealis Award for Best Young Adult Novel, and named an 'Unsung Hero of 2009'

‘The Gypsy Crown’ was nominated for a CYBIL Award in the US and for the Surrey ‘Book of the Year’ award in Canada in 2009

In Australia, where ‘The Gypsy Crown’ was sold as a 6-book series, Books 2-6 won the 2007 Aurealis Award for Children’s Fiction & Book 5: ‘The Lightning Bolt’ was a CBCA Notable Book

'The Starthorn Tree' was shortlisted for the 2002 Aurealis Award for Best Children’s Fantasy & the Western Australian Children's Choice Awards and chosen for the One Book, One City campaign in Brisbane

Yet I'd always dreamed of winning something BIG, something international ... the Nobel Prize for Literature, for example ....

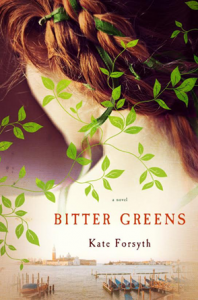

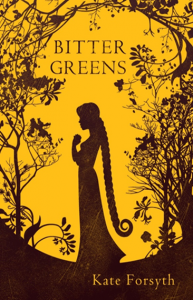

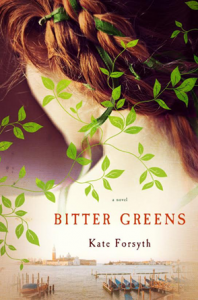

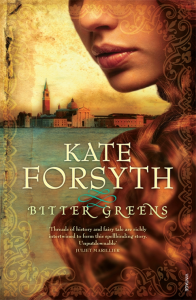

Well, I'm very happy to say BITTER GREENS, my retelling of the Rapunzel fairy tale, has won the American Library Association (ALA) award for Best Historical Fiction in 2015.

The ALA is the oldest and largest library association in the world, and its prestigious awards include the Caldecott Medal, the Newbery Medal, the Carnegie Medal, and the Michael L. Printz Award.

BITTER GREENS was also a Library Journal US Best Historical Novel, and was shortlisted for the Aurealis Award, the Ditmar Award, and a Norma K. Hemming Award (for which it received an Honourable Mention).

BITTER GREENS around the world:

I have a secret page on my website that only those that search carefully can find. I call it The 50/50 Project ...

It is a list of all my hopes and dreams - both possible and impossible - & all the places I hope to one day go and all the things I hope to one day do. I call it The 50/50 Project because it was inspired by the inching closer of my 50th birthday and the realisation that there are still so many things in the world I want to do (I found 50 of them, hence the title). The idea is that - as I go somewhere or achieve something - I'll blog about it, and gradually be able to cross off some of these dreams.

Today I am crossing off:

No 49: Win A Major Literary Prize

I have been short-listed for lots of awards and won a few.

‘The Puzzle Ring’ was short-listed for the 2009 Aurealis Award for Best Young Adult Novel, and named an 'Unsung Hero of 2009'

Yet I'd always dreamed of winning something BIG, something international ... the Nobel Prize for Literature, for example ....

Well, I'm very happy to say BITTER GREENS, my retelling of the Rapunzel fairy tale, has won the American Library Association (ALA) award for Best Historical Fiction in 2015.

The ALA is the oldest and largest library association in the world, and its prestigious awards include the Caldecott Medal, the Newbery Medal, the Carnegie Medal, and the Michael L. Printz Award.

BITTER GREENS was also a Library Journal US Best Historical Novel, and was shortlisted for the Aurealis Award, the Ditmar Award, and a Norma K. Hemming Award (for which it received an Honourable Mention).

BITTER GREENS around the world:

To plot, or not to plot – that is the question ...

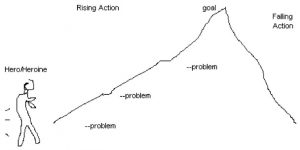

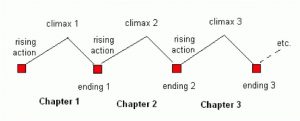

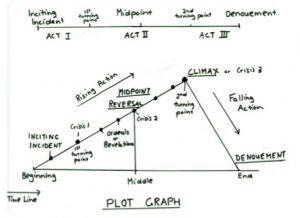

Exposition – Rising Action – Climax – Falling Action – Denouement

1. set-up scene – a scene of normal life or “the ordinary world”. Often called EXPOSITION. If I have such a scene at all, I try and keep it as short as possible.

2. Inciting Incident – the true beginning – sets story in motion. Called the “call to adventure” in Joseph Campbell's The Hero's Journey.

3. period of turmoil/confusion. Campbell called it “refusing the call”

4. The First Turning Point (must happen within the first 25% of action). Campbell suggested a story at this point often involves a “meeting of the mentor” and then “acceptance of the call, which leads to the protagonist crossing "the First Threshold". Usually it is a moment of decision, or realisation, which leads to a momentous step being taken. I like to think of it as a gateway into a new state of being, a moment of psychological change.

5. Rising Action – a series of incidents, each increasing in tension and suspense. Joseph Campbell called this 'The Road of Trials' which I like, as it gives the sense of ever increasing difficulties. I normally like to plan the Road of Trials quite carefully, making sure that each scene or incident has a narrative function - each event is a revelation to be understood, an obstacle that must be overcome, an ordeal to endure, a lesson to be learned. I like the outer journey to reflect the inner journey of the protagonist's process of change and transformation.

Last week I did an hour-long interview with Richard Fidler on his hugely popular ABC Radio Show 'Conversations' (click the link to listen to the whole interview). Among other things, I spoke about my great-great-great-great-grandmother, Charlotte Waring Atkinson, who wrote the first children's book published in Australia. I have had such a huge response from the show, and so many questions about this incredibly strong, brave and clever woman, that I decided to post an article I wrote for Australian Author some years ago to celebrate the 170th anniversary of the book's publication:

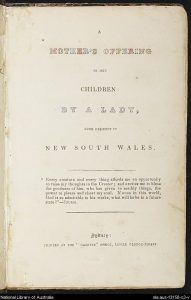

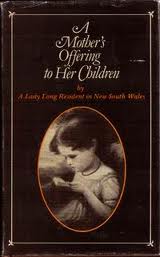

Frontispiece of the first edition of A Mother's Offering To Her Children by A Lady Long Resident in New South Wales, first published in 1841

‘Heirs of Immortality’

Who was the mysterious ‘Lady’ who wrote Australia’s first children’s book?

Nowadays, Australian children’s authors such as Shaun Tan, Melina Marchetta, Sonya Hartnett, John Marsden, and Garth Nix are as well-known internationally as they are here.

Yet how many people know the name of Australia’s first children’s writer?

A Mother’s Offering to Her Children was published 174 years ago by a woman known simply as ‘A Lady Long Resident in New South Wales’. For almost a century and a half, her identity was Australia’s most puzzling literary mystery. In the 1960s, Marcie Muir - a passionate lover of Australian children’s literature - set herself the task of finding out who this anonymous ‘Lady’ was. She could never have anticipated that she would uncover one of the great lost stories of Australian history, a tale of courage, grief, violence, and triumph in the face of overwhelming odds.

So who was the ‘Lady Long Resident in New South Wales’?

She was a child prodigy who could read by the age of two.

She was a fiercely independent young woman who scandalised Sydney society with her determination to forge her own way.

She was a widowed mother of four who singlehandedly ran one of the largest land grants in early New South Wales.

She was probably raped by an infamous bushranger, the man later dubbed the Berrima Axe Murderer.

She was a battered wife who fled her “raving lunatic” of a second husband, even though it left her homeless and penniless.

She was the mother of the first Australian-born female novelist.

She was also my great-great-great-great-grandmother.

Marcie Muir (1919-2007) was a collector and bibliographer of Australian children’s books whose passion became an obsession. Her library of over 7000 books – many of them extremely rare – was bought last year by the National Library of Australia. There was one book, though, that she was never able to afford to buy. A first edition of A Mother’s Offering To Her Children is now valued at $60,000. Even sixty-odd years ago, it was worth more than Marcie Muir could afford to pay.

In 1978, a second edition was printed by Jacaranda Press, with a foreword by Rosemary Wighton, author of Early Australian Children’s Literature. She says, ‘For many years it was believed, because of a hand-written note in one of the surviving copies, that the author was Lady Gordon Bremer ... This attribution now seems increasingly dubious ... a letter from one of Lady Gordon Bremer’s descendants to the bibliographer of Australian children’s books, Marcie Muir, states that, as far as family records show, she never visited Australia at all.’

When this second edition was published, Marcie Muir had already spent almost a decade trying to identify the author of A Mother’s Offering, searching through ancient newspapers, scrolling down endless microfiches, and writing to anyone who might be able to help.

One day, in the summer of 1978, her doggedness at last paid off. Marcie Muir had flown to Sydney to look through Mitchell Library’s newspaper archives, in particular those of 1841, the year A Mother’s Offering was published. In The Sydney Gazette, on the very last newspaper of the year – 23 December 1841 – she found a small review tucked away at the back.

It said: ‘(A Mother’s Offering to Her Children), which embraces a variety of useful and entertaining matter, is got up under the form of dialogues between a mother and her children. It is to be hoped that others will follow the noble example set up Mrs Barton ... nothing sooner gives young persons a taste for refined literature than books ... which while ... interesting, are also instructive.’

A name! ‘Mrs Barton.’ Yet who was Mrs Barton?

Nobody seemed to know. For another eighteen months, Marcie Muir tried to find out. Eventually, wearied of her task, she gave up and turned her attention to another literary mystery – identifying the author of the first illustrated children’s book, Peter Possum’s Portfolio.

Finding an advertisement for it in the back of Cowanda, the Veteran’s Grant, an 1859 novel by the colonial writer Louisa Atkinson, Marcie Muir wondered if she could also have been the author of Peter Possum’s Portfolio. Louisa Atkinson was an accomplished novelist, artist and naturalist, and well-known as Australia’s first native-born female novelist.

Marcie Muir began to research Louisa Atkinson’s life and work. To her astonishment, she discovered that Louisa Atkinson’s mother – born Charlotte Waring – had remarried a man named George Barton when Louisa had been only four.

Could the mother of Australia’s first native-born female novelist also be the author of Australia’s first published children’s book?

The idea fascinated Marcie Muir. She plunged into research on the Atkinson family and eventually made contact with the descendants of the Atkinsons, who had many drawings and papers which were able to conclusively prove that it was indeed Louisa Atkinson’s mother who was the mysterious ‘Lady’ Marcie Muir had been searching for.

Born in 1796, Charlotte Waring was the third of four sisters. Her mother died giving birth to her younger sister, and Charlotte was raised by her father, a man of fortune whose ancestors had come to England with William the Conquerer. Charles Darwin was her fifth cousin, and her father, Albert Waring, was a younger son of Lord Saye and Sele. Charlotte was a brilliant child who could read fluently at the age of two and who received an unusually good education.

When she was fifteen, her father died, and Charlotte’ young half-brother inherited all his wealth and property. Charlotte and her sisters were left impoverished and, like many a heroine of a Bronte novel, were forced to find work as governesses.

Yet Charlotte was strong-willed and strong-minded, and used to a life of privilege. When a position was advertised for the princely price of 100 pounds a year, Charlotte leapt at the chance. Unlike the 24 other applicants for the job, she was not daunted by the idea of travelling halfway round the world to the tiny colony of Sydney, although she had read newspaper accounts of attacks by savage natives with spears, escaped convicts, bushfires, and smallpox epidemics.

She had one stricture. She would only go if she travelled first class.

At first Mrs King, the wife of Admiral Phillip Parker King, was effusive in her praise of the governess she had hired for the Macarthurs. A few weeks later, however, she wrote to her husband, “I am very much disappointed in Miss Waring the Governess, she is very different from what she ought to be ... We had not been 2 hours on board before I saw she was flirting with Mr Atkinson, and ere 10 days were over she was engaged to him … she told me … she must be mistress of her own actions.’

Charlotte Waring left Plymouth on 19th September 1826, a penniless governess with few prospects. She arrived in Sydney on 22nd January 1827, engaged to James Atkinson, a rich gentleman-settler.

James Atkinson had landed in Sydney in 1820, only thirty-two years after the arrival of the First Fleet. He had been given two land grants totaling 2,000 acres as a reward for his services in the Colonial Secretary’s Office. This land, called Oldbury after his father’s manor in Kent, was at Sutton Forest, 140 kilometres south of Sydney. He was good friends with the Kings and the Macarthurs, and his book, An Account of Agriculture and Grazing in NSW, had just been published in London to great acclaim.

Their romance scandalised Sydney. Alexander Berry, writing to Edward Wollstonecraft, said ‘I must say I never saw a lady whose manners were less to my taste … the grossest levity!’ Mrs King wrote ‘she behaved very ill and gave herself many airs’, though, as Marcie Muir was to write, ‘there is more than a little malice in Mrs King’s tone, inspired by her disapproval of the governess she had engaged daring to become betrothed to a gentleman of their acquaintance.’

Charlotte and James were married on 29 September 1827 and went to live at Oldbury, where they built a grand sandstone manor which still stands today (though not, sadly, owned by my family). Four children were born in quick succession - Charlotte Elizabeth (my great- great-great-grandmother), Jane Emily, James John Oldbury and Caroline Louisa Waring (known as Louisa).

A photo of Oldbury Farm as it is today, taken by my sister Belinda Murrell

When Louisa was only two months old, James died and Charlotte was left alone, the mistress of a vast, isolated property worked by convicts and the mother of four children under the age of six. In a repeat of her childhood tragedy, Oldbury was left in trust for her son, then only two years old.

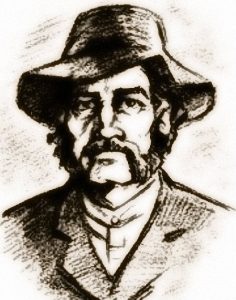

Almost two years after James’s death, Charlotte and her overseer, George Barton, were visiting an outlying property when they were held up and robbed by bushrangers, led by the notorious escaped convict John Lynch, later to be named the Berrima Axe Murderer. Lynch whipped Barton cruelly, saying he “considered it his duty to … flog all the gentlemen so they might know what punishment was.”

A drawing of the infamous bushranger and Berrima Axe Murder, John Lynch

Charlotte herself may have been raped. Since she never spoke of that day, we cannot be sure but certainly her own family came to believe so. Whatever happened that terrible day, it led Charlotte to make the greatest mistake of her life.

One month later Charlotte married George Barton. He was a violent drunk. When asked to testify against Lynch in a court of law, he turned up so incapacitated by alcohol that Lynch was acquitted and went on to murder another ten people. Louisa Atkinson was to write of her step-father: ‘(he) became a furious maniac and had to be kept under restraint.’ In time Barton would be charged with murder, and sent to gaol.

After three terrible years, Charlotte and her four young children fled Oldbury. They took only their clothes, Charlotte’s jewellery box, the children’s pet koala, and her writing desk, tied to the back of a bullock. They travelled at night down the precipitous Meryla Pass and through the wild gorges of the Shoalhaven River, at last reaching Sydney some months later. Charlotte had no income at all from Oldbury, supporting her family by the sale of her clothes and jewellery, and by running up debts.

For the next six years, Charlotte would fight not only for the allowance she was entitled to under her dead husband’s will, but also for custody of her children. The executors of the will – Alexander Berry and John Coghill – maintained she was ‘not a fit and proper person to be the Guardian of the Infants … in consequence of her imprudent … intermarriage with George Bruce Barton.’ This accusation must have been a bitter pill for Charlotte to swallow, as she had run away from her violent husband and had already applied to the courts for protection from him.

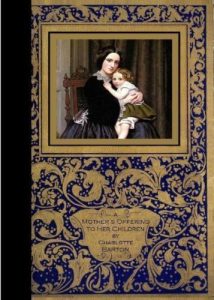

In the meantime, Charlotte had to find some way to house, feed, clothe and educate her children who were ‘literally starving’. So she wrote a book, the first children’s book to be published in Australia. It was released in December 1841, in time for the Christmas trade. Cleverly, A Mother’s Offering was educational enough to appeal to early Victorian sensibilities and yet still exciting enough to appeal to children, filled as it was with descriptions of storms, shipwrecks, strange animals, fossils and cannibals. It was an instant bestseller, and provided Charlotte with an income until her son was at last old enough to inherit Oldbury.

Structured as a dialogue between a mother and her four young children, the book is hard to read now, with all its moral instructions and outmoded Victorian sensibilities. Yet it was the first book in the world to draw upon Australian history, the first to feature native trees, birds and animals, the first to describe life as a settler, the first to feature the life and culture of the Australian Aborigines. I have to remind myself of this because, I must admit, the first time I read it I was horrified at her racism. It is hard to remember that Charlotte was writing in the early 19th century, and that her depiction of “the natives” was considered rather too sympathetic at the time.

A sketch of a local Aboriginal woman with her child, drawn by Charlotte Waring Atkinson

By the time the book was published, Charlotte had resoundingly won her case, though she was fined in court for her ‘impertinence’. The Chief Justice, Sir James Dowling, ruled: “It would require a state of urgent circumstances to induce the Court to deprive them (all of whom are under thirteen years of age) of that maternal care and tenderness, which none but a mother can bestow.”

A Mother’s Offering To Her Children was based on stories that Charlotte had told her own children, who had lost everything - their father, their wealth, their home. She told them stories to teach them, to entertain them, and to comfort them. With her stories, she created an enchanted circle where those four fatherless children knew that they were loved.

Charlotte Waring wrote in her final paragraph of A Mother’s Offering to her Children: ‘we know not the day, nor the hour, when time may cease for us; and we be summoned into eternity. Let us, dear children, endeavour to profit by the frequent warnings we have of the uncertainty of life … (Let us) so pass through this life that we gain a knowledge of the things which belong to our peace; and become at last heirs of immortality!’

To celebrate the 170th anniversary of the publication of her book, the Children’s Book Council of Australia (NSW Branch) has announced they plan to rename the Frustrated Writers’ Award in her honour, so that her name – unknown for so long - shall at last be remembered.

(The primary sources for this article were Charlotte Barton: Australia’s First Children’s Author by Marcie Muir (Wentworth Books, 1980), Pioneer Writer - The life of Louisa Atkinson: novelist, journalist, naturalist by Patricia Clarke (Allen & Unwin, 1990) and oral history passed down by the descendants of James and Charlotte Atkinson.

My sister has written a wonderful novel about the Atkinsons entitled The River Charm, which I hope you will all read.

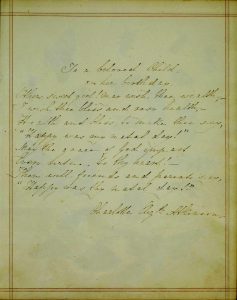

And just finally, a note in regards to Charlotte's name. As a result of Marcie Muir's book, Charlotte is known as Mrs Barton ... but my great-great-great-grandmother hated and feared her second husband, took out a restraining order against him, and never called herself by that name. To the time of her death, she called herself Charlotte Atkinson, as can be seen by this sketchbook she made for her eldest daughter, also called Charlotte. No-one in the family would ever call her by the name Mrs Barton, and we all hope that others will respect her wishes and not call her that either!

Q: Your books seem extremely well researched. Not only in the history of the culture, but in the magical elements and practices as well. Could you explain to us the importance of this research, or how you went about it?

I do a great deal of research into every aspect of the books. I like to make sure everything is right and besides, I find the research itself often sparks off ideas which I would not have had otherwise. It helps make the world seem real and alive, and gives an extra punch to the writing. Generally, I borrow piles of books from the library and read through them, making notes on all that interest me. I often find the junior section of the library the most helpful because the books there have illustrations and diagrams, and describe things simply and concisely. For example, if I'm writing a battle scene I want to know everything about armour, weapons, siege machines, tactics, logistics - a book on mediaeval warfare from the adult section would be too long and heavy, but a selection of books from the junior library give me just about everything I need to know. As well as that, I browse a lot through second-hand bookshops and so have picked up heaps of books on all sorts of different subjects, all of which give me ideas and allow me to check facts when I need to. I have everything from a 16th century herbal to a dictionary of angels, all of which I've referred to at some point in time.

Q: Have you noticed, or have readers commented, that your story, while not a sad story and definitely containing the "good" vs. "bad" elements in it, leaves one feeling unsure whether to laugh or to cry?

I really like this question and am glad to know this is how the books make you feel. I certainly wanted to make my readers laugh and cry and gasp and sigh at different points in the story, and I also wanted to express something about the complexity of good and evil and how sometimes there is a very high price to pay. None of my characters or creatures are entirely good or entirely evil - sometimes evil is done by those who are really struggling to do what is right. I get a lot of e-mail from readers and this is one of the things people comment on the most - a particular scene makes them want to get up and shout a warning, or makes them cry, or makes them very frustrated with the characters in question - all of which makes me a very happy writer!

Q: Do you have a favorite character in the books?

Many. I love them all. Isabeau is of course my protagonist and I love her dearly, though sometimes I wish she would think before she acted, particularly in the early books. I find Iseult rather a puzzle sometimes, and am rather glad Lachlan is beginning to grow into his manhood, for he exasperated me greatly at times with his bad moods and his self-focus. I love Meghan, of course, and have very tender regard for Lilanthe and Dide and Finn. In fact, I don't think there is really a character I don't have a soft spot for, unless it's Margrit who gives me the shivers and Renshaw, of course, who was very nasty.

Q: How long do you see this story continuing? Is it only to be a three part series, or will you go on with it?

This is a difficult question to answer in many ways. Yes, of course they have relevance to our world and express many of my deeply felt beliefs and philosophies. I have a great deal of sympathy for the pagan pantheistic religion of my witches. I am troubled by the effect of strict fundamentalist religions, in whatever form they take, and I am troubled by the effects of colonism and the long-reaching shadows it has cast. I think religion and patriotism have caused a great deal of evil in this world, even though I understand the deep, instinctive desires that such beliefs satisfy. I also understand there are no easy answers and that history has a way of repeating itself. I hope all these ideas are implicit in the books but I do not want to pontificate too much upon them, for the books should stand alone, speaking for themselves. They are not allegories or even vehicles for my concerns, and should not be read as such.

Q: Can you give us a mouthwatering hint for the Americans as yet unable to read the fourth book?

Gladly! Of all the books so far, 'The Forbidden Land' is the simplest and most complete in itself. It moves very quickly and has less introspection than the others. The primary focus in this book has moved to Finn the Cat, the cat-thief who discovered she was a banprionnsa and heir to the throne of Rurach. She feels stifled and unhappy at Castle Rurach and when Lachlan the Winged, Righ of Eileanan, calls upon her own peculiar talents, she gladly sets off on an adventure that takes her beyond the Great Divide and into the heart of the Forbidden Land itself ...

Q: What has the Internet meant for you as an author?

BOOKS THAT HAUNT A CHILD FOREVER

Bertrand Russell said, ‘There are only two motives for reading a book: one, that you can enjoy it; two, that you can boast about it.’

Children, of course, rarely read a book for any other reason than enjoyment. And there really should be no other reason to read.

Books give us entertainment and escape, refreshment and relaxation, and even, perhaps, wisdom.

The best of them also bewitch us, giving us some sense of beauty and astonishment that stays with us all of our lives.

One of my favourite writers, Susan Cooper, wrote about one of her favourite writers, Walter de la Mare:

“I’ve had my copy of this wonder for thirty years and must have turned to it at least as many times each year –

sometimes for solace, sometimes for sunlight, always with an emotion that I have never quite been able to define.

Come Hither is my talisman, my haunting: a distillation of the mysterious quality that sings out of all the books

to which I've responded most deeply all my life -

and that I deeply hope as a writer I might someday, somehow, be able to catch.”

That quote says exactly what I feel most passionately about books and about my writing. I too want to write books that become talismans,

to write books that have that “mysterious quality that sings”.

Susan Cooper’s The Dark Is Rising is a book that has haunted me all my life.

So too:

Philippa Pierce’s Tom’s Midnight Garden

Lucy Boston’s The Children of Green Knowe

Elizabeth Goudge’s The Little White Horse

Ursula le Guin’s The Wizard of Earthsea

Joan Aiken’s The Wolves of Willoughby Chase

Diana Wynne Jones’s Charmed Life.

There are, of course, others.

These, however, are my magic seven, the ones I have returned to so many times

their flimsy paperbacks are falling to pieces in my hands.

What all these books have in common is a sense of wonder and mystery,

a feeling that adventure and magic is lurking just around the corner.

They are also silver-tongued. The writing is vivid and supple and lucent.

The characters are alive, dancing and joking and fighting and fearing

and losing and sorrowing and prevailing at sometimes a great cost.

They sing.

Lucy Boston once wrote:

"I believe children, even the youngest, love good language, and that they see, feel, understand

and communicate more, not less, than grownups.

Therefore I never write down to them, but try to evoke that new brilliant awareness that is the world.’

Me too!

Every book I have ever written is in homage to these writers – among others –

and these books – among others. I'm a passionate advocate of books which empower children -

books which teach children they have the chance to choose

what they become, and that their choice can change the world.

Jane Yolen - another favourite writer of mine - said:

“A child who can love the oddities of a fantasy book

cannot possibly be xenophobic as an adult.

What is a different color, a different culture, a different tongue for a child

that has already mastered Elvish, respected Puddleglums,

or fallen under the spell of dark-skinned Ged, the greatest wizard Earthsea has ever known?”

In a speech I gave recently, I said, 'I love writing for children aged about eleven or twelve.

It was the age in which I first really discovered books and reading.

It was the age in which I laid down my idea of the world and how it works.

The books I read then are the books which I have carried with me all my life.

At this age, I can still hope to surprise and enchant my readers.

I can still hope to save them.’

Until I said this, I did not know that was what I longed for.

Yet I do.

To haunt my readers with beauty, to astonish them with the strange and the miraculous,

to help them realise they have the power to change the world.

This is what I, as a writer, deeply hope I might someday, somehow, catch and pass on.

You can buy THE PUZZLE RING at Booktopia, Dymocks, Collins, Angus & Robertson Bookworld, or read it on your Kindle

Dear Kate

I am the teacher of a year 3-4 class in a small rural school, just outside Hamilton, in New Zealand.

I picked up a copy of Book 1, The Impossible Quest - Escape from Wolfhaven Castle at a literacy conference in 2013. I returned to school and immediately read it to my class. The children were totally engaged and enthralled with the story, so much so I actually stopped reading one day as they were so still and silent (this doesn’t often happen!)

The following year I read books 1-3 to my class and they were hanging out to read book 4 & 5. This year I was lucky to have the same group of children (small school!) and so we have read book 4 & 5.

I had purchased book 5 online and so displayed this on the screen for the children to read along with me. What an experience that was for both myself and the children. We were all hanging out to get to the end of book 5 and what an ending. It was very satisfying!

Many of the children have independently read the book again. We had several hypothesis regarding the sleeping heroes, who Jack might be and of course the realisation that Quinn was in fact a queen. The whole way through the series we were kept guessing, just like the children in the novels. The children have written some comments about the novels that they wanted to share with you. They were also wondering if there was any chance that this might be made into a movie. These children are all 8 years old.

What I liked most about your books are that they’re all rescue missions which I think is the awesome part. That’s what I think is extraordinary about your books – Prue

Your books are awesome. It was great in the Battle of the Heroes, when the Mortlakes were captured in the cages - Chase

I liked your books because they have really good words and the action is very exciting. Kloey 8 years

I really like Quinn. I also liked the very last sentence in Book 5… They all laughed knowing that none of them believed anything was impossible any more. Lacy

Your books are interesting. I like your titles of the books. Drayden

I love your Impossible Quest series. They are so unique and extraordinary. I’ve read the whole series myself! I especially like Book 5. It’s got so much drama. I love all of the fantasy animals. When I grow up I want to be an awesome author like you. Ashlee

What I liked about your story is how you made people fight and I also liked Fergus. Khaled

I like most about the Impossible Quest is the adventures in the book. I liked Fergus. Brad

I liked the characters and the weapons in your books. Luke

I like your books because they are very good and they excited me when I when I read the first one. Phoenix

I really liked how you wrote book 5 because it really excited me with all the scary parts. Phoebe.

I really liked the adventures that the children had. Saige

What I liked most about your Impossible Quest book 5 was that I thought it was very extraordinary. My favourite characters were Quinn, Wolfric and Beltain. Your books blow my mind. Jessica.

I like the Impossible Quest books because there are adventures in each book. My favourite characters are Quinn and Quickthorn. The first book was absolutely astonishing. They had to escape Wolfhaven castle. Book 3 was epic because they found Beltain the dragon. Thank you for making the Impossible Quest series. Alexa

I liked Impossible Quest 5 because of the heroes. The heroes are extraordinary and Quinn, Eleanor, Tom and Sebastian and the other characters are all awesome. Micaiah

I liked the adventures the children had and their animals. My favourite one was the unicorn, Quickthorn, Wolfric and Fergus. Cassie

Once again, thanks for writing such an appealing, engaging and enthralling series of books that are appropriate for our younger readers.

Kindest Regards

Leanne Adam Class

Teacher Rukuhia School, Hamilton, New Zealand

A few months ago, I gave a speech on fairy tales at the Wheeler Centre in Melbourne. I've had a lot of queries from people who were unable to make it for various reasons (including vast distances) and so I've summarised my speech into a couple of blogs so everyone may enjoy. Here is a brief rundown on fairy tale retellings and ways to use them in your own creative work ...

A fairy tale retelling is a story which retells or reimagines a fairy tale, or draws upon well-known fairy tale symbols and structures.

Fairy tale retellings deal with personal transformation - people and creatures change in dramatic and often miraculous ways. Many fairy tales hinge upon a revelation of a truth that has been somehow hidden or disguised.

Fairy Tale Retellings are most often written as a fantasy for children or young adults.

Some of my favourite fairy tale retellings for young adults

Not all, however. In recent years, there have been a number of beautiful, powerful and astonishing fairy tale retellings for adults too.

Some of my favourite fairy tale retellings for adults

My own novel BITTER GREENS is a sexy and surprising retelling of the 'Rapunzel' fairy tale, interwoven with the true life story of the woman who first wrote the tale, the French noblewoman Charlotte-Rose de la Force . It moves between Renaissance Venice and the glittering court of the Sun King in 17th century Versailles and Paris, imagining the witch of the tale as a beautiful courtesan and the muse of the Venetian painter Titian.

There are many different ways to draw upon fairy tales in fiction. Here is a brief overview:

“Pure” Fairy Tale Retellings

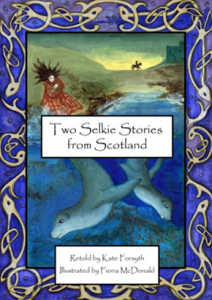

A retelling of a fairy tale in which few changes are made to the best-known or ‘crystallised’ sequence of action and motifs. Changes tend to be small and subtle, such as adding dialogue or rhymes, naming characters, describing the setting more vividly, or smoothing out any inconsistencies. My picture book TWO SELKIE TALES FROM SCOTLAND, beautifully illustrated by Fiona McDonald, is an example of a "pure" fairy tale retelling.

Fairy tale Parodies

Stories in this genre parody fairy tales for comic effect – they are usually done in picture book form, though sometimes writers do so in longer fiction also.

Fairy Tale Pastische

A pastiche is a work of literature which celebrates the work that it imitates i.e. it is a new work which copies or mimics the style of an older literary form. A fairy tale pastiche therefore sounds like it comes from the ancient oral tradition, but is entirely new

Sequels, prequels and Spin-Offs

Many fiction writers take a well-known fairy tale, and then create new stories that tell of the events which happened before or after the pattern of action in the 'crystallised' tale.

Fairy Tale Allusion & Intertextuality

Some novels can draw upon fairy tale motifs, metaphors and plot patterns in more subtle ways.

A girl may wear a red hoodie, or red dancing shoes.

A young woman may be poor and under-valued, yet still win the heart of the most eligible bachelor

A dark forest may be a dark city … a tower may be a hospital …

My novel DANCING ON KNIVES is a contemporary romantic suspense novel set in Australia, yet it draws upon Hans Christian Andersen's well-known fairy tale, 'The Little Mermaid'. My heroine Sara is not at home in the world. She feels as if she cannot breathe, and every step causes her pain. She is haunted by the ghosts of the past, and must learn to be brave before she can begin a new life for herself. The fairy tale elements are used only as allusion and metaphor, and as a structural underpinning of the story.

Retelling well-known tales from another Point of View

Another way to reinvigorate a well-known fairy tale is to tell the story from an unexpected point of view. I was always interested in the motivations of the witch in 'Rapunzel', and so knew right from the beginning that she would be a major point of view in BITTER GREENS. Here are a few other books which make the villain the protagonist of the story:

Retelling well-known Fairy Tales in unexpected settings

Another way to revitalise a well-known fairy tale is to set it somewhere startling or unexpected. I have spent the last year working on a retelling of the Grimm Brothers'version of 'Beauty & the Beast', set in Nazi Germany. THE BEAST'S GARDEN will be released in late April 2015.

Books About Fairy Tales & Their Tellers

As I noted earlier, BITTER GREENS is a retelling of the ' Rapunzel' fairy tale interwoven with the true life story of the woman who first wrote the tale, Charlotte-Rose de la Force. As an author and oral storyteller, I am very interested in the tellers of the tales. In my novel, THE WILD GIRL, I tell the story of the forbidden romance between Wilhelm Grimm and Dortchen Wild, the young woman who told him many of the world's most famous fairy tales, against the dramatic background of the Napoleonic Wars in Germany.

Retelling Little Known Fairy Tales

You do not need to only drawn upon the best-known fairy tales. There are many hundreds of beautiful, romantic and beguiling fairy tales that are not as well-known as they should be. In THE GYPSY CROWN, I retell some old Romany folk tales. In THE PUZZLE RING, I was inspired by Scottish fairy tales and history. In THE WILD GIRL, I shine a light upon some of the forgotten Grimm tales. In THE IMPOSSIBLE QUEST, I play with old Welsh tales.

The only limits are your own imagination!

FURTHER READING: