I was recently approached by an aspiring author who asked my advice – I thought I’d share with you my response in case it is of help to anyone else:

I am currently writing my first novel (in between juggling work and being a mother to my 2 year old son which has made the process slower than I'd like!) and would appreciate your thoughts on the following if possible:

Q: Would you recommend going through a literary agent or going directly to a publisher? And what do you think is the best way to connect with them?

It really depends on what kind of book you are writing and how you wish to be published. If you are writing the kind of book that is likely to appeal to a traditional mainstream publisher, then I’d definitely try to get an agent as they can submit your manuscript to the most likely editors, negotiate the contract for you, make sure you are paid, and then help you manage and strategise your career. My agent and I work very closely together and I couldn’t manage without her.

There are lots of literary agencies who all specialise in different things. Start researching them and begin a spreadsheet with information on them i.e. agents’ name, contact details, what kind of books they represent. You can find out a lot on the internet, but also look in the author’s acknowledgements at the back of books you love and see who they thank. Your spreadsheet will help you make a list of 12-15 agents who you would most like to work with – and also agents who you know can’t help you so you won’t waste your time and theirs by approaching them.

Q:Some websites I've read have said you only need to send a brief synopsis and first chapter but others have said it's good to provide a complete manuscript. What have you found to be the case?

Each agent and publisher will have submission guidelines on their websites – for each individual submission check their guidelines and follow them exactly. For a debut author, you’ll want to have your novel in the best possible shape before submitting – so work on the premise that they’ll want to see a complete manuscript and get it as perfect as you can.

Q:I wondered if you had any advice about the writing process in general. Do you typically conduct all your research and plot the novel in detail before starting to write it, or is your research/writing process slightly more fluid?

I do most of my research and plotting before I begin, but once I start writing I find the story grows organically and fluidly and my plan may change. I have just developed an online self-paced planning course that will be going live in a month or so – I teach the whole process of plotting and structuring a novel in great detail. I think you’d find it really helpful so keep an eye out on my social media and sign up for it – you can do it in your own time and at your own pace, and receive handouts you can keep for future reference.

Finding your own creative process is a big part of your journey as a writer, and every writer is different, so at this stage trust your story and your process, and do whatever you can to keep pushing the narrative forward. I know it’s hard with a little one! But I wrote all through my kids’ childhoods so I know it can be done.

Q:I'm sure a big factor of your success has been the ability to dedicate time to the writing process too and I wondered how you find juggling everyday life with your writing and blocking out distractions, etc?

Thank you! That’s so kind of you.

I have always been a fierce defender of my writing time. Only my first book was written without kiddies – and at that time I was making my living as a freelance journalist and so very short on time and creative energies.

What worked for me was having a set writing routine. When my children were very small, like yours, I wrote when they slept (which was never often enough). That meant an hour or two a day while they napped, and evenings and early mornings. I found that if I got up an hour earlier than they did, and went straight to my computer in my pyjamas and dressing gown, I was able to get quite a few words down before they woke up and the havoc of the day began. That eased my frustration at not being able to write – and then when they napped, I could read over what I’d written, fix it up, push it along a little – and so it was always growing and I stayed connected to it, thinking about it, and wanting to get back to it.

I’d also have at least one night a week where I’d write in the evenings too – usually Monday night as it meant that I could get the week off to a good start.

Then I had an arrangement with my husband that Saturday was his free time (he went to the football usually) and Sunday was mine. He’d take the kids out to the beach, or the museum, or the park, and I’d write. Often I’d write in my pyjamas because having a shower would bite into my writing time too much! That meant I’d get 3-4 hours straight writing time, and it made all the difference. I also got very used to writing in the cracks of the days.

I never used my child-free time for anything else but writing. It’s much easier to do housework or grocery shopping and so on without kids, but I never did it else I’d not get to write.

The other thing I do is be really strict about what else I do with my time – i.e. watching TV, mucking about on social media, flicking through magazines or whatever. Focus and discipline, focus and discipline, focus and discipline …. This was my mantra for years.

It sounds very stern and resolute and difficult to do, but it’s really not that hard once you get used to it. If you can find an hour a day to write most days, or 4-5 hours to write one day a week, you’ll be surprised how much you can get done.

If you need a dose of creative inspiration and joy, check out my Dare to Dream online course HERE:

And when you are ready to submit your manuscript, check out Query Shark. They’re funny, clever, and give great advice on how to go about it.

Fabulous February!

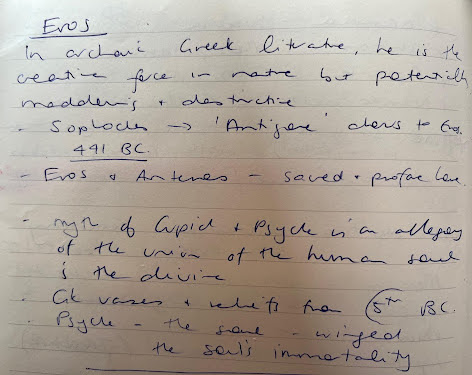

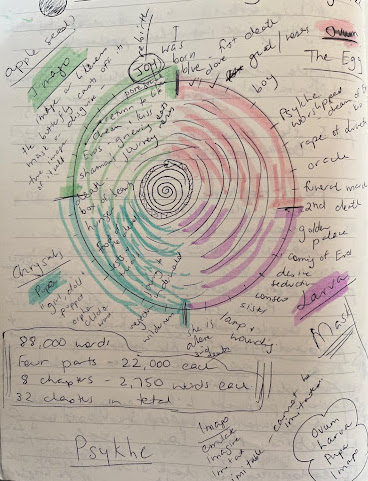

I’ve had a wonderfully restorative holiday, but am back at my desk now, scribbling madly away. I’m hard at work on my new novel-in-progress Psykheand planning my research trip to Italy in May. I have crossed the 20,000 mark which means I’m close to a quarter of the way through the novel (I‘m aiming for under 100,000 words!), and can feel the story quickening within me.

You can read all about Psykhe on my writing journal blog here, or follow me on social media for updates and insights. Here is a sneak peek at my Psykhe notebook:

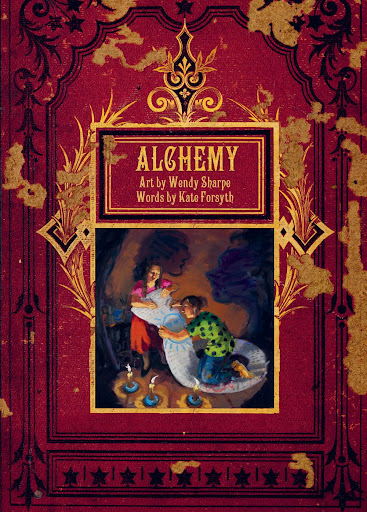

In other news, we’re having a launch of Alchemy, the book I wrote with Wendy Sharpe, at the Art Gallery of NSW:

Wednesday 22 February 2023

6pm

$15 for a non-member

$10 for a member, which includes a complimentary drink in the Members Lounge.

You can book through the art gallery on (02) 9225 1878 – be quick because I heard today spots are filling quickly.

Here's the blurb:

Alchemy is a bold and beautiful collaboration between two very different artists. Kate Forsyth is an award-winning novelist, poet, and storyteller. Wendy Sharpe is one of Australia’s most acclaimed and awarded artists. Together they pour their words and images into an imaginative crucible to create a powerful narrative of a woman’s life.

Birth to Death.

Child to Crone.

Innocence to Wisdom.

Lead to Gold.

A unique book that combines the best of Kate Forsyth’s writings with the best of Wendy Sharpe’s images-a collage of poems, quotes, and creative reflections layered with photos, drawings, doodles, paintings and found objects.

You can buy it at any good bookstore, or through Upswell Publishing’s website HERE:

Meanwhile, The Crimson Thread was back in the bestseller lists, climbing to No 7 on Audible. Like to listen? Click HERE

Until next time

Kate x

Alison Croggon is an award-winning novelist, poet, theatre writer, critic and editor who lives in Melbourne, Australia. She works in many genres and her books and poems have been published to acclaim nationally and internationally. She is arts editor for The Saturday Paper, and her most recent book is her memoir Monsters, published by Scribe Publications in Australia, Britain and the US. She is also the author of the wonderful epic fantasy series The Books of Pellinor.

Alison was kind enough to take some time out of her hectic schedule to answer a few questions for me:

Have you always wanted to be a writer?

Yes! Or at least, all of my conscious life. I can’t remember learning how to read and write – I could do both when I started school in England, and according to my mother wrote a poem on my first day. My first teacher wrote to me for years after we moved to Australia, saying that one day she would buy my books. So I guess the written word was embedded in my most basic conceptions of my self.

All writers have different journeys to publication – please tell me yours.

My first published book was a collection of poetry, published by Penguin Australia when they used to do that sort of thing. It happened after I had my first baby, after I had been through a bit of a crisis about me and my writing and something that maybe in retrospect I can recognise as PPD. In any case, a lot of people who had supported my work wrote me off after I became a mother, and one said to my face “there’s the end of a promising young poet”. Words that are obviously branded on my brain! Ironically enough, that is also the time I began to take myself really seriously as a writer. I remember deciding very clearly that even if I was never published, I still would write. And so I did.

It was kind of liberating, before then I had stressed about being published, like it would mean I was finally a proper writer. Anyway, not long after I had decided that it didn’t matter, Judith Rodriguez saw me reading at La Mama and she called me up and asked for a manuscript. At first I thought she was asking me to do another reading so I sounded a lot more casual than I would have otherwise. I’m still really grateful to her. She was a great woman.

Your new book Monsters has been described as a hybrid between memoir and essay – the very word ‘hybrid’ conjures the idea of a monster! What drew you to such an unusual structure for your story? Which came first? The essays on race, culture and history, or the memoir about your difficult relationship with your sister?

Weaving between different forms in prose kind of came naturally, I think, a kind of shifting of lenses to try to see things from different angles... It’s not the first time I’ve played with this form, I wrote a memoir/essay/fiction thing called Navigatio in the mid-90s – actually when my youngest son Ben was a new baby, so I wrote when he was asleep – with chapters alternating between memoir/essay and fantasy/fiction. It was my first long prose work (still quite short, it was about 100 pages). Monsters kind of reworks many of the same obsessions as Navigatio, with (I hope) a bit more insight. Neither theme – my relationship with my sister or the essays around culture – really came first, I think I needed to think through both of them at once. But I always wanted to look at entwining of the macro and the micro, it was never conceived of as a purely personal book.

My first thought was that it was going to be a book that looked at what happens to relationships between women under patriarchy, but I did a lot of genealogical research and in my family there’s just no escaping that I come from a long line of British colonists. That heritage is something I’ve attempted to deal with for a long time – I don’t feel guilty about it, it’s not that simple, but owning and acknowledging what that means seems very important to me. And I do believe that heritage as colonists shapes our intimate relationships in ways that we are not conscious of and that are often very damaging. I wanted the book in a way to enact that exploration, both emotionally and intellectually.

The book is very raw and painful in parts. Tell me about your journey toward writing this book. What made you decide to write about your sister? Do you think it has helped you understand your relationship better? Has it helped your sister understand you?

It was certainly the most painful book I have ever written. It was even harder than I expected. I wrote it because it felt necessary – I don’t think there was a single decision, it was more a series of decisions. It’s the only book I’ve ever pitched (mostly I write books in full before offering them to publishers). I felt I needed a good editor as I was working on it, an outside eye to ensure that I wasn’t being merely self indulgent or any of the other perils that come with this sort of work. I am so grateful to Scribe for publishing it and to David Golding for being such a superb and sensitive editor.

As for better understanding? The answer is yes and no. Some people have written me absolutely amazing emails about how the book has helped them, illuminating things for them in a way that they found useful, starting them on their own paths to rethinking their personal and wider histories and how they stand in the present, and that is gratifying – that is actually what I wanted the book to do.

Personally, it’s been a mixed bag. My mother read Monsters and had the worst nightmares of her life for two weeks, and I felt so guilty – but then she wrote to me saying that she had been carrying around this awful sadness for decades, and that she realised that the book had lifted it away and it didn’t come back. That alone justified it for me.

My sister reacted very badly. Of course she has every right to think whatever she likes about the book, and I knew she wouldn’t take it well, although I was a bit shocked by the extremity of her response. I do feel sad that this book, which was so much about wanting to get beyond assigning fault, in her case absolutely reinforced it. I didn’t write Monsters to be a J’accuse. But she absolutely took it that way and things got very messy indeed. Two years after it came out, I think that Monsters has been a bit of a clarifying moment within the family. Some of the things that have been made clear are very saddening. But they were things that were always there, anyway.

In what way is your relationship with your sister linked to your thoughts about race, culture and history?

I guess the relationship is dysfunction. I started noticing that the things that were wrong between us – the binaries of good and bad, the projections, the denials, the exploitativeness, the refusal of complexity, and so on – were the same behaviours that I often saw in what’s called white fragility and also in misogyny, and more largely in analyses and historical accounts of colonialism. I think I was particularly interested in how whiteness clings to a primordial innocence, almost foundationally, to the point that we will brutalise and abuse others in order to preserve it. Like I say somewhere in the book, there is a kind of fractal patterning in these behaviours. And I wanted to tease it out.

It’s a book I wrote specifically for white people, in the hope that it might directly enable thinking through the inherited habits and shapes of thought that harm us and others. I can’t deny (now) that there was a tiny hope that my sister might also find it helpful, or that she might understand me a bit better, but in the book I do talk about my pessimism about that – maybe the one thing I’ve learned over the past few decades is that speaking and listening are two different things, and that you can’t force anyone to listen if they don’t want to.

Like me, you are an author whose work defies easy categorisation. You write poems, essays, plays, fiction, and now memoir. You’ve translated one of my favourite poets, Rainer Maria Rilke, from the German. You’ve written absolutely brilliant fantasy novels for both young adults and middle grade readers, and collaborated with Daniel Keene with two dystopian cyberpunk science fiction novels. And you’re also the arts editor for The Saturday Paper. So I’d love to ask you a few questions about your writing processes.

What is your preferred medium?

I expect you’re the same – it just depends! Different ideas and feelings demand different forms of expression. All of it is writing, and each work responds to some specific impulse.

How easily can you move from one genre or mode of expression to the next?

Again, it depends. I’ve done a lot of shifting from one thing to another. I don’t know if you find this, but for me sometimes the shifting can be more exhausting than the work. I think with creative work I just follow the currents in my brain? I’m certainly a great believer in trusting the subconscious and in letting it do its thing. You learn to feel when something is ready to be written. Last year I barely wrote anything at all, and it was amazingly wonderful. Laying fallow is also so important!

Where do you write, and when?

Always in my study at home. And mostly in the morning, these days. I work part time, which is brilliant, and (in theory, anyway) I use the other days in the working week to write.

How do you keep juggling all the balls?

Panic, maybe? I do know it’s taken a toll: I don’t get burned out, I think because I love my work, but I can get truly exhausted. This year my resolution is to be patient and to work without anxiety or expectation. So far, so good...

What is your favourite part of writing?

Editing. I love editing. (I also love editing other people’s work.) First drafts of books are almost without exception kind of traumatic. I know that sounds a bit – well, indulgent – but they do feel that way? Emotionally exhausting and weirdly, also physically exhausting. I always write blind, I seem incapable of planning things out, and so I’m never quite sure what I’m doing. But once something is down, I can get to work.

What do you find most difficult?

The middles. I usually love beginnings, when everything is fresh and exciting, and endings are exhilarating, like running downhill, but middles are, without exception, reaallllly hard.

What do you do when you get blocked?

I take some time out and do something useful.

How do you keep your well of inspiration full?

I’m actually not sure. Mainly I try to pay attention to where I am, whatever it happens to be. Sometimes in writing a particular work, I can feel that my perceptions start narrowing, as if I begin with everything possible and then it seems I can only see two or three things, so I think I try to make sure that my mind is moving in ways that are about opening up rather than closing down.

Do you have any rituals that help you to write?

Beyond habits – a cup of coffee, walking around the house in circles (widdershins, of course) – I don’t think so?

Who are ten of your favourite writers?

This is a really hard question. There are so many writers I adore, so many who have been important to me at different times, so many who have opened doors and shown what’s possible… I’ll try to list ten writers who have been constant stars in my erratic navigations, but I could do another ten and have a totally different list.

Ursula Le Guin, Edward Said, Audre Lorde, John Berger, Alexis Wright, Muriel Rukeyser, Terry Pratchett, Oodgeroo Noonuccal, Gillian Rose, Helen Macdonald...

What do you consider to be good writing?

This is also a hard question! Good writing for me is the kind of writing that feels like you’re inhabiting someone else’s mind, that you have this intimate and clear connection with another consciousness, which opens doors to realities and possibilities that are not yours or that you have always suspected were possible but never quite saw so clearly or in that way. (I hope that makes sense!) Sometimes that means breaking rules, but like Granny Weatherwax says, if you’re going to break rules, you have to break them good and hard.

What is your advice for someone dreaming of being a writer too?

You need patience and resilience. And to be absolutely pragmatic. I’d tell a young writer to get a steady job to pay the bills – it’s harder and harder now to make an income from writing and being poor is more stressful than having a job. Assign your time carefully, and preserve time that is only for you. And learn everything you can about syntax, form, traditions and so on – the best way to do that is by reading as widely as possible. Read everything – all kinds of fiction, philosophy, history, criticism, poetry, graphic novels. The better you know your tools, which include your own mind, the more you can break the rules. Breaking the rules without knowing what they are usually means bad writing, and you want to be able to break the rules.

What are you working on now?

A middle grade fantasy novel (presently called The Other Place) set in the 1930s about a girl called Sarah who is a child magician. She accidentally vanishes her best friend and discovers that magic is real. And then things happen...

You can read my review of Black Spring, Alison’s wonderful retelling of Wuthering Heights HERE

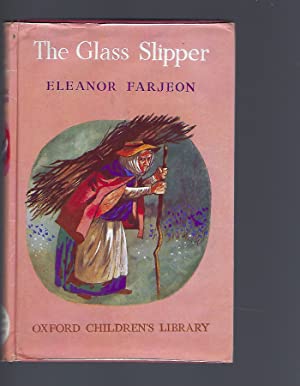

If there is any joy in this world greater than discovering a new book to love, it is rediscovering one that you have loved and lost.

I willingly confess to being a bibliomaniac. This is, according to Maurice Dunbar, ‘a victim of the obsessive-compulsive neurosis characterized by a congested library and an atrophied bank account.’ Our house is inhabited by books, old ones, new ones, those still waiting to be read, ones that have been re-read a hundred times. There are books on every imaginable subject, for I like to be able to put out my hand and find the answer to whatever question is haunting my curiosity. Most of my books, though, are fiction. ‘Fiction is king,’ as Francis Spufford wrote so cajolingly in ‘The Child that Books Built’; (another book I love). ‘Fiction is the true stuff, compared to which non-fiction is just a shadow.’

‘We hope,’ he wrote, ‘(that fiction) can bring a fully uttered clarity to the living we do, which is, we know, so hard to disentangle and articulate. And when it does, when a fiction does trip a profound recognition … the reward is more than an inert item of knowledge. The book becomes part of the history of our self-understanding. The stories that mean most to us join the process by which we come to be securely our own.’

It is Spufford’s argument that the books we read over our lives, but most particularly the books we read as children, that make us who we are. All of us who are ardent readers will be able to name those books which had the most profound effects upon us at different times of our lives. My memory of my childhood is vague and fragmentary at best, yet I can remember every book I ever read and usually where I was when I read it. As I like to own books, this means I will often hunt for years to find a book that I’ve read and loved and lost. Since many of the books I read as a child are now out of print, this means I love jumble sales, church fetes, and second-hand bookshops. I love all bookshops, but the old ones have a special allure about them, the hope of stumbling across Aladdin’s cave in a box of shabby old paperbacks.

Just yesterday I found a book I have been searching for since I was seven years old. That’s thirty-two years of looking. The book was ‘The Glass Slipper’ by Eleanor Farjeon. I borrowed it from my school library and was utterly enchanted by it. I remember I began reading it on my way home from school (I often used to read while walking home from school, and today, whenever I see a child doing the same, I always smile with a real sense of warmth and comradeship). I became so engrossed in ‘The Glass Slipper’ that I walked straight past the end of my street, and only came to myself four blocks further on, when my sister’s best friend’s mum honked me as she drove past, laughing.

I turned myself about and read all the way home. I finished the book on the way down the stairs to the dinner-table that night, and was as replete and satisfied as any glutton after a king’s feast. I borrowed the book again several times, and when I left my primary school for high school, it was one of the things I most regretted having to leave.

Perhaps the best way for me to describe the shaping power this book had on my imagination is to confess I named my daughter Eleanor, and that we call her Ella for short, a name for which I’ve had a soft spot ever since reading this classic retelling of the Cinderella tale. It would be untrue to say that Eleanor Farjeon and her sweet-faced heroine Ella were the only influences on my choice of name. Ellen is a family name, and I’ve always liked Queen Eleanor of Aquitaine, and often thought I would like a tombstone like hers – she lies sculpted in stone on the lid of her tomb in the Abbey of Fontevrault, holding open a book. It would be true to say that Eleanor Farjeon and this book were strong influences, however, which goes to show just what a profound recognition it tripped in me at the age of eight.

‘The Glass Slipper’ is one of the books that began my lifelong fascination with fairytale retellings, and with tales of magic and marvel, one which drives my writing today. It is told simply, but with such wit and humour, charm and playfulness, that it is far fresher than any other version of the old tale I’ve read. Yet it is not a book that can be bought in any good bookstore – it has been out of print as long as I’ve been alive. Most people have never even heard of Eleanor Farjeon, yet she wrote more than thirty works of fiction, three plays, thirty-three collections of poetry, and numerous biographies and memoirs. There is an award for children’s literature named after her in the UK, and she wrote the words to the hymn ‘Morning has Broken’, which Cat Stevens turned into a mega-hit in the early ‘70s.

Born in 1881, the daughter of a novelist and granddaughter of an actor, Eleanor Farjeon was brought up in a household of books, and encouraged to write from an early age. At the age of eighteen, she wrote the lyrics to an operetta penned by her brother Harry which was performed at St George’s Hall in London. At nineteen, she sold her first story for three guineas, a fairytale called ‘The Cardboard Angel’ She counted D.H. Lawrence, Walter de la Mare and Robert Frost among her friends, and received the Hans Christian Anderson Medal in 1956.

‘The Glass Slipper’ was first written with her brother Herbert as a play in 1944, and turned into a book in 1955. Eleanor’s love of poetry and song comes through in every line – it has the sort of playfulness with language that is rarely seen nowadays.

‘When (Ella) was refused (permission to go to the ball), she clung to the last few minutes of the spilt finery, the hasty scramble out of the house, the little squeaks and shrieks on the slippery path: ‘It’s freezing! It’s freezing! Go carefully! Hang on to me! stop gripping me! you’re tripping me! Oops! Ma was nearly down that time! I’m petrified! I’m paralysed! Stop dragging me! stop nagging me! I’m dithery! It’s slithery! OOOPS! Ma was really down that time! We’ll be late, we’ll be late! Look alive, look alive! The horses are waiting at the end of the drive …’

Eleanor Farjeon once wrote of herself, ‘I can hardly remember a time when it did not seem easier to write in running rhymes than in plodding prose,’ and this facility with rhythm and rhyme can be heard on every line.

It is, of course, a strange and poignant experience, reading again as an adult a book one had loved as a child. The scales of innocence are lost from our eyes; we have inherited a world-weariness along with our wisdom. I always loved Enid Blyton when I was seven, but reading her now to my seven-year-old son, I cannot help grinning when one of her bossy boys says ‘I came over all queer.’ I find myself subtly editing as I read, even though I strongly disapprove of trying to modernize old stories, much of whose charm comes from the stiltedness and strangeness of the language.

Reading ‘The Glass Slipper’ again, I was conscious of the distance between myself as a child, discovering the tale for the first time and being utterly enchanted, and me as an adult wishing Ella would be a little less sweet to her nasty step-sisters. Yet now that I have it in my hand again, I cannot wait to read to my own children, and particularly to my own Ella, the story of Cinderella, “barefoot, tangle-haired and tattered, but with a face as fresh as a flower.’

I am deep into the world of Psykhe, my new novel-in-progress, and thought I would share with you a little of what I’m writing about. It’s a new departure for me – a retelling of an ancient myth known by most people as ‘Amor and Psyche’, or ‘Cupid and Psyche’. It is a haunting tale of love and loss and redemption which follows a young woman’s journey to the underworld and back as she seeks to atone for her betrayal of her beloved. Her story has been told for more than two-and-a-half thousand years. It is the source myth for such beloved fairy tales such as ‘Beauty and the Beast’, and also the lesser-known variants ‘The Snake Prince’ from Greece and ‘Zelinda and the Monster’ from Italy. I’ll be drawing upon these beautiful old stories in my version too.

I’ve always loved the story. It is one of the few myths in which a woman does not have her tongue cut out, or her hair turned to hissing snakes, or her life reduced to a plaintive voice echoing men. It celebrates female desire and disobedience, and its denouement leads to love and liberation, not sorrow and suffering.

In the best-known version, 'Eros & Psyche', written by Lucius Apuleius in the 2nd century AD, Psyche is condemned to be married to a winged serpent but is rescued by Eros and taken to a secret palace where he visits her that night, making her 'his wife' even though she is afraid and unwilling. However, in the fairytale variants, usually told by women, the heroine's consent is integral to the breaking of the curse upon the beast-husband, and so that is one element I will be changing.

I’m setting my novel is ancient Etruria, at the time of the Roman kingdom. This is because the oldest known artistic representation of Amor and Psyche was once found in an ancient tomb in the Etruscan necropolis at Tarquinia called the Tomb of the Passage of Souls. It has since been lost, the opening of the tomb almost obliterating the image, but luckily an archaeological artists named James Byres drew a quick likeness of it. It shows Psyche depicted with butterfly wings. In ancient Greek, the word ‘psyche’ means both ‘the breath of life’ and ‘butterfly’, and so the story of Psyche symbolises the redemptive power of love and desire over darkness and despair.

One final question you may have – why am I entitling my novel ‘Psykhe’? Two reasons. Firstly, it’s closer to the original Greek name before it has been Anglicised. And, secondly, it contains my own initials within it. My maiden name is Kate Humphrey and for years I used to scribble my initials as KH.

You can read more about the myth and my inspirations Here

And if you are a lover of C.S. Lewis, like me, you can read my review of his Amor and Psyche retelling Here

And, finally, you can listen to me read my version of ‘The Singing, Springing Lark’, a German derivative of ‘Beauty and the Beast’ Here

Jane Morris as ‘Proserpine’ Painted by Dante Gabriel Rossetti (1871)

Jane Morris was an English embroiderer and artists’ model who embodied the Pre-Raphaelite ideal of beauty, her face appearing on many paintings created by her husband William Morris and her lover Dante Gabriel Rossetti. She died on 26 January 1914, at the age of seventy-four. I have been fascinated with her since I was a teenager and first heard her story.

I was nineteen years old, an impoverished university student, living out of home for the first time, so poor I could scarcely afford to eat.

I was starved of beauty.

One day I saw a poster hanging in a shop window that stopped me in my tracks. A woman with heavy dark hair and a sorrowful face, loosely dressed in green silk, holding a pomegranate in her hand. The fruit had been split open to show the red pulp within. Behind her, a faint glimpse of light.

In the lower left-hand corner of the painting was a scroll inscribed with ‘Dante Gabriele Rossetti,’ a name I had never heard before.

In the upper right corner was some poetry written in Italian. I recognised the name ‘Proserpina’, another form of Persephone.

She was the goddess of spring, kidnapped by Hades and condemned to spend six months of the year in the underworld after eating just six pomegranate seeds. During her imprisonment, the whole world grew cold and barren. Winter clamped upon the earth for the first time.

It was my favourite Greek myth.

The poster was on sale for twenty-five dollars. I opened my wallet and saw that I was one dollar short. It was all the money I had. If I spent it I would not be able to eat for a week. But I knew I had to have it. The man in the shop agreed to sell the poster to me. As he rolled it up, I said timidly, ‘She’s very beautiful.’

‘Oh yes. She was famous for her face,’ he told me. ‘Rossetti painted her hundreds of times. They were madly in love, but she was married to one of his best friends and so they couldn’t be together.’

Beauty. Art. Myth. Poetry. Love. Heartbreak. It was all there, everything that most drew me, in that one richly coloured and mysterious painting.

So began my lifelong fascination with the Pre-Raphaelites.

The woman with the sorrowful face was named Janey Burden, and she was born in a slum in Oxford.

Her father was an ostler at an inn, her mother an illiterate laundress who signed her marriage certificate with an X. Janey lived with her parents and brother and sister in a single room not much bigger than the stalls where the horses were kept.

One evening in autumn 1857, to celebrate her eighteenth birthday, Janey and her sister Bessie went to see a travelling theatre group perform at the local gymnasium. There she caught the eye of an exotic-looking gentleman with ruffled dark curls and paint under his fingernails. His name was Dante Gabriel Rossetti. He was the eldest son of a fugitive Italian scholar, and the nephew of John Polidori, famous for being Lord Byron’s doctor and author of the infamous novel The Vampyre. Gabriel (as he was called by his friends) wanted to be both a poet and an artist, and divided his time between writing, drawing and roaming the streets looking for pretty girls.

By 1857, the Brotherhood had fallen apart but Gabriel had found a new circle of friends and admirers who had accompanied him to Oxford to paint some murals on the walls of Oxford Union’s debating hall. Among this new brotherhood were Edward Burne-Jones (then plain old Ned Jones) and William Morris (nicknamed Topsy). Ned and Topsy were best friends who had defied their families to pursue their dreams of art. They hero-worshipped Gabriel and followed his lead in everything.

As soon as Gabriel saw Janey, he was struck by her unconventional beauty. She was quite unlike the Victorian ideal of beauty, being tall as a man and slender as a willow wand, with heavy masses of dark hair, a bee-stung mouth, and a long strong nose. Her looks were so un-English that many would speculate that she had Gypsy blood in her. Gabriel accosted her at the end of the performance and asked her to come and model for him. After some hesitation, Janey agreed and changed her life forever.

Gabriel was ten years older than Janey, handsome, brilliant and charming. It was little wonder that she should fall in love with him. But Gabriel was not free. He had been entangled in a tumultuous affair with another woman for the past seven years.

Her name was Lizzie Siddal, and she was delicate, highly-strung and thought to be dying of consumption.

In all likelihood, her malady was anorexia nervosa but this was a psychological disorder that had not yet been identified, and so her frailty and refusal of food puzzled the many physicians who saw her. Lizzie was an artist and poet too, and had been the only woman to have her work exhibited in the first Pre-Raphaelite exhibition earlier that year.

Gabriel and Lizzie had become engaged a few years earlier, but somehow the marriage had never taken place. Hearing rumours about Gabriel and Janey, she wrote to him and begged him to come to her. Gabriel obeyed reluctantly. The Oxford set was broken up, the murals left unfinished. William Morris, however, stayed in Oxford. He was trying to paint Janey as the tragic queen Iseult.

Jane Burden, ‘Iseult’

By William Morris (1858)

One day he wrote on the back of the canvas, ‘I cannot paint you but I love you.’

Topsy was stout and rather awkward, but he was also kind and rich. Janey was a slum girl who had been abandoned by her lover. His offer of marriage was not something she could easily refuse. They were married in 1859, after Janey had spent months being taught how to act like a lady. She was the original Eliza Doolittle, and I mean that literally - George Bernard Shaw knew her well, and she inspired his play ‘Pygmalion’.

A year later Gabriel married Lizzie, after promising her on her death-bed that they would be wed if only she would get better. They had been lovers for more than eleven years.

A scant two weeks later, Ned married Georgie Macdonald, a sweet-faced nineteen-year-old who also dreamed of creating art. Topsy built a grand Art & Crafts manor in the Kentish countryside called Red House, and the three couples spent many happy weekends painting murals on the walls, embroidering tapestries, and playing hide-and-seek by candlelight. Together they created the company that is now known as Morris & Co, creating fabrics, wallpaper, stained glass, hand-painted tiles and furniture. Janey could embroider exquisitely, and she created many designs that helped make Morris & Co famous.

The joyous times could not last, however. Janey gave birth to a healthy little girl in January 1861, but - a few months later – Lizzie gave birth to a stillborn daughter. She sank deep into postnatal depression. One day Georgie and Ned found her rocking an empty cradle and singing lullabies to a baby who was not there.

Six months later, Lizzie died of a laudanum overdose. The inquest found death by misadventure, but rumours of suicide have abounded ever since. Racked with grief and guilt, Gabriel buried his only manuscript of poems with her. Haunted by her ghost, he painted her face compulsively and began to hold séances in the hope of reaching her. He filled his house with a menagerie of exotic animals – including peacocks, owls, raccoons and a wombat – and rarely left the house in sunlight. He drank too much and began to self-dose himself with chloral hydrate, a highly addictive sedative.

In the summer of 1865, Gabriel hosted a party at his grand house in Chelsea. Topsy and Janey were guests. Gabriel had not seen Janey since Lizzie’s death. Struck anew by her wild, dark beauty, Gabriel asked her to sit for him once again. Janey agreed at once. He began to paint her as obsessively as he once drawn Lizzie. In 1868, he created a magnificent portrait of her in a blue silk dress, a red rose at her waist. The frame was engraved with the words: “Famous for her poet husband, and most famous for her face, finally let her be famous for my picture!”

Portrait of Mrs William Morris in A Blue Silk Dress

Dante Gabriel Rossetti (c.1868)

By that time, Topsy had won great acclaim with his epic poem ‘The Earthly Paradise’. Jealous of his success and in love with his wife, Gabriel began to wish he had not been so impetuous in burying his own poetry in Lizzie’s coffin. In October 1869 – seven years after her death - Gabriel secretly obtained a court order to have her dead body exhumed so he could retrieve his manuscript, riddled with wormholes and reeking of rot.

One of the few remaining pages of Gabriel’s poetry manuscript which had been buried with Lizzie

– now at the British Library

The Victorians had a morbid fascination with death, which they policed with rigid mourning rituals. The news of the exhumation caused a scandal, fuelled by the whispers of Gabriel and Janey’s secret affair.

Cuckolded by his idol, betrayed by his wife, Topsy acted with his usual kindness and refusal to bow to convention. He took out a joint lease with Gabriel on a beautiful Elizabethan manor house on the River Thames in Kent, then travelled on his own to Iceland. Gabriel and Janey and her two daughters, Jenny and May, spent an idyllic summer at Kelmscott Manor, far from the outraged eyes of London society.

It was then that Gabriel began his portrait of Janey as Proserpina. In his eyes, she too was condemned to a loveless marriage, their world as bleak and barren as winter. Only in those few sweet heedless months of summer could they both escape and be free to love as they pleased. It was there that he wrote the sonnet later inscribed upon the painting. It read, in part, ‘this … dire fruit which, tasted once, must thrall me here … Woe’s me for thee, unhappy Proserpina’.

As the long summer days drifted past, Gabriel wrote many love poems for Janey. He copied them into a small leather notebook for her, each word thrumming with longing and desire: ‘all sweet blooms of love/To thee I gave while Spring and Summer sang;/But Autumn stops to listen, with some pang … Only this laurel dreads no winter days/Take my last gift; thy heart hath sung my praise.’

But the world could not be shut out.

The scandal intensified, with Gabriel’s art and poetry being excoriated in the press. Tortured by guilt, racked with insomnia, Gabriel had a nervous breakdown. In June 1872 – ten years after Lizzie’s death – he tried to commit suicide with an overdose of laudanum. He was revived, but was left paralysed down one side. His addiction to whisky, chloral and laudanum grew fiercer. In 1876, unable to bear it any longer, Janey broke off their affair.

In 1882, Gabriel painted Janey as Proserpina for the eighth and final time, except that he gave her Lizzie’s mane of fiery red hair.

A few days later, he died.

Janey lived for another thirty-odd years, spending much of her time in the old manor house on the river where she had been so happy so briefly.

She kept his notebook of love poems all her life.

It was this story which inspired me to write my novel ‘Beauty in Thorns’ which tells the little-known story of Georgie Burne-Jones, Jane Morris and Lizzie Siddal. You can read more HERE

and the book HERE

Gingerbread houses have long been associated with Christmas, along with gingerbread men, angels, stars, and trees. It is often said that gingerbread houses were inspired by the fairy tale ‘Hansel and Gretel’, and as I am always fascinated by fairytale lore, I set out to discover if this was true.

The history of this delicious spice is ancient. Originating in Malaysia, ginger travelled the spice roads over land and sea to the Middle East, and then was spread through Europe by the Crusaders in the 11th century. Monks were the first to make honey cakes infused with ginger, to celebrate saint’s days and festivals (hence its close association with Christmas). Soon, gingerbread was being made all over Europe, but particularly in England, France, and Germany where they were sold at fairs in the shape of shape of suns, moons, flowers, birds, or other animals. It was Queen Elizabeth who invented gingerbread men; she instructed her cook to make them for visitors, each one decorated to represent the man or woman to whom it was being given.

For a long time, only professional gingerbread bakers were allowed to make the delicious repast. France’s gingerbread guild began in 1571 while Germany’s came into being in 1643, with Nürnberg becoming the centre of the trade. Gingerbread guilds employed master bakers as well as woodcarvers who created beautiful stencils and patterns to press into the dough, artists to decorate with frosting, and goldsmiths who painted it with gilt (hence the expression ‘take the gilt off the gingerbread.’

Gingerbread houses came into being in Germany in the early 19th century, where they were called lebkuchenhäusle. This means they were contemporaneous with the ‘Hansel and Gretel’ fairy tale, which was collected by the Grimm brothers between 1808-1810 and published in 1812 in the first edition of their famous fairy tales. It is believed the story was told to Wilhelm Grimm by Dortchen Wild, whom he would later marry (I tell her story in my novel The Wild Girl . She certainly contributed the children’s answer to the witch, ‘The wind, the wind, the heavenly child,’ which rhymes in German: ‘der wind, der wind, das himmlische kind.’

However, there is no gingerbread house in the earliest versions of ‘Hansel and Gretel’. All the different versions published by the Brothers Grimm described a house made of bread with a roof of cake and windows of sugar. All subsequent translations of the story into English describe the witch’s house in the same way.

The first mention of gingerbread appeared in 1895, when the Australian folklorist Joseph Jacobs rewrote the story for a collection called Europa's Fairy Book, under the title ‘Johnnie and Grizzle’. He described the witch’s house as follows: ‘the door was made of butter-scotch, the windows of sugar candy, the bricks were all chocolate creams, the pillars of lollypops, and the roof of gingerbread.’

Yet every modern-day version of ‘Hansel and Gretel’ invariably describes the house as being made of gingerbread. This kind of analogical reformation is sometimes called ‘folk etymology’, where the original occurrence or meaning of a word is replaced by another as a result of popular usage.

So the motif of the gingerbread house was added to the fairytale as a result of the popularity of lebkuchenhäusle, not the other way around. And delicious, warming gingerbread can be eaten at any time of the year, not just at Christmas!

Here’s an old traditional recipe, with thanks to the wonderful blog Sew Historically

Medieval Lebkuchen recipe

1 Maß honey

1 1/2 Pfund sugar

1 Vierling flour

1 Lot cinnamon

3 Lot nutmeg

1 1/2 Lot cloves

6 Lot ginger

1 Quintel mace

rosewater

The recipe was published in The Cookbook Of Sabina Welserin. Sew Historically did a lot of research into the weights, measures and terms, and re-interpreted the recipe as follows:

Modern-day Lebkuchen recipe

2 tsp cinnamon

1 tsp nutmeg

1 tbsp cloves

3 tbsp ginger

Coarsely crush the spices using a mortar and pestle. Combine flour and coarsely ground spices in a large bowl.

Combine honey and sugar in a pot and bring to a boil. Pour the hot honey over the flour-spice-mixture. Knead everything together. Or it works just as well, to just stir everything together with a large spoon. Now let the dough rest for about 30 minutes or 1 hour.

On a floured surface, roll out the dough to about 1/2″ (1cm). Cut out rectangles with a knife. Transfer the medieval gingerbread to lined baking sheets. If you want, you can decorate the lebkuchen with blanched almond halves.

Let the lebkuchen rest overnight at room temperature.

Preheat the oven to 350°F (180°C). Brush the top of the gingerbread with rosewater.

Bake the lebkuchen for 20 minutes. Put the lebkuchen into cookie tins immediately after you remove them from the oven while still hot.

And enjoy!

Image credit: https://cookidoo.thermomix.com/recipes/recipe/en-US/r370249

The Blurb (from Goodreads)

After a storm has killed off all the island's men, two women in a 1600s Norwegian coastal village struggle to survive against both natural forces and the men who have been sent to rid the community of alleged witchcraft.

Finnmark, Norway, 1617. Twenty-year-old Maren Bergensdatter stands on the craggy coast, watching the sea break into a sudden and reckless storm. Forty fishermen, including her brother and father, are drowned and left broken on the rocks below. With the menfolk wiped out, the women of the tiny Northern town of Vardø must fend for themselves.

Three years later, a sinister figure arrives. Absalom Cornet comes from Scotland, where he burned witches in the northern isles. He brings with him his young Norwegian wife, Ursa, who is both heady with her husband's authority and terrified by it. In Vardø, and in Maren, Ursa sees something she has never seen before: independent women. But Absalom sees only a place untouched by God and flooded with a mighty evil.

As Maren and Ursa are pushed together and are drawn to one another in ways that surprise them both, the island begins to close in on them with Absalom's iron rule threatening Vardø's very existence.

Inspired by the real events of the Vardø storm and the 1620 witch trials, The Mercies is a feminist story of love, evil, and obsession, set at the edge of civilization.

My Thoughts:

I love books which illuminate true events in the past, particularly if they are little-known and deal with women, and other outsiders whose lives are so often not been recorded for posterity.

The Mercies is inspired by true events in early 17th century Norway. Inspired by the Scottish witch-hunts of James IV, King Christian began a crusade of religious persecution and witchcraft trials that saw the indigenous Sámi people and poor, superstitious women targeted. In all, fourteen Sámi men and seventy-seven Norwegian women named as witches were executed.

The novel begins with a freak storm that kills all the men on a small village on the far northern Norwegian coast. The women need to band together to survive, even as they struggle to recover from their shock and grief. Twenty-year-old Maren Bergensdatter has lost her father, her brother, and her betrothed. She is haunted by nightmares and paralysed by sorrow. Slowly she begins to rebuild her life, working alongside other women in the village, but their strength and independence is seen as unwomanly and soon a man is sent to rein them in. His name is Absalom Cornet and he worked in Scotland to burn witches. With him comes his young and lonely Norwegian, Ursa. The two young women are drawn together, but their close and passionate friendship endangers them both.

I loved it! One of the best books I’ve read this year.

The Blurb (from Goodreads)

In a kingdom where magic is banned and rules abound, Princess Emer escapes to the forest. When an accursed raven pecks her hand, Emer is transformed and finds herself at the heart of a war between her mother and her aunt. Only the Crown of Feathers can set them all free, and Emer must find it and her true self along the way.

My Thoughts:

Flight spins together two dark & eerie fairytales – ‘The Raven’ and ‘White Bride, Black Bride’ into something utterly new & enchanting. Princess Emer is transformed into a raven, and must set out on a perilous journey to break the curse. Gorgeously illustrated by the one & only Kathleen Jennings, this book is an absolute treasure. Just divine.