THE STORY DOCTOR

So many people email me asking me for writing advice I have decided to begin a new section on my blog where I share my answers to these questions.

Over time, I hope to build a wonderful resource for aspiring writers to help them diagnose what may be ailing their story ...

Dear Kate

I heard you speak one time about the importance of controlling narrative distance in your writing, and what a useful tool it can be in writing from a 3rd person perspective. Can you please explain a little further?

I can!

Deciding what Point-of-View (POV) to use when writing a novel is one of the earliest decisions an author makes. As you would know from grammar lessons at school, there are three types of POV:

1st person – I

2nd person – you

3rd person – he/she

Sometimes it’s an easy choice. The voice of Charlotte-Rose de la Force, the protagonist of my novel Bitter Greens, came to me very clearly in 1st person: I was always a great talker and teller of tales …’

There are actually three narrative strands in Bitter Greens, two of them told in 1st person and one in 3rd person, which is an unusual authorial choice. I had a good reason for that choice (though to explain why would be a spoiler!)

I knew from an early stage of the novel that The Wild Girl would be told in close 3rd person: ‘Wild by name and wild by nature,’ Dortchen’s father used to say of her. He did not mean it as a compliment. He thought her headstrong and so he set himself to tame her.

(Close 3rd person simply means that there is only one point-of-view all the way through the novel).

I initially wrote The Beast’s Garden in close 1st person, but then – after a great deal of agonised heart-searching – decided the book was not working as well as I wanted, and so I rewrote the entire book in multiple 3rd person (which means more than one POV). \

I fell in love the night the Nazis first showed their true faces to the world

was changed to:

Ava fell in love the night the Nazis first showed their true faces to the world.

It was a slow, difficult, back-breaking process. I could not blithely use the global change facility in my word processor – I had to go through every page line-by-line, checking it again and again, rewriting every sentences, every scene.

So why did I choose to go through the agony of changing POV?

There were several key reasons, but most important to me was that multiple POV allowed me to tell my story from many different angles, across times and geographies; and because 3rd person POV has one huge advantage over 1st person.

The use of the objective narrator.

When writing in 1st person, the author must always stay deep within that character’s consciousness, privy only to their thoughts and feelings and only ever speaking in their voice. Their POV is therefore necessarily limited.

However, when writing in 3rd person, the writer can move fluidly between the voice of the objective narrator and the deep, close point-of-view of the character.

Not sure what I’m talking about?

Now might be a good time to talk about narrative distance.

Narrative distance is the feeling of closeness between the reader and the point-of-view of the characters. It is, of course, controlled by the author and is part of what creates a distinctive “voice.”

John Gardner explores the idea in his book The Art of Fiction – though he calls it ‘psychic distance’. He defines it as ‘the distance the reader feels between themselves and the events in the story.’

Basically, it's how deep the reader is taken inside the character's head. Gardner has defined five different levels of engagement:

1 It was winter of the year 1853. A large man stepped out of a doorway.

2 Henry J. Warburton had never much cared for snowstorms.

3 Henry hated snowstorms.

4 God, how he hated these damn snowstorms.

5 Snow. Under your collar, down inside your shoes, freezing your miserable soul.

The first example creates the greatest distance between reader & character, but is the most effective for delivering information. Each new example takes us deeper into the character’s individual point of view, and – in the final two examples – into the character’s own voice. The deeper the author goes, the more is revealed about character and the less about anything else.

The deeper you go, the more important is the character’s individual “voice”.

When writing in 3rd person POV, the writer draws upon all five states of narrative distance, for different purposes and for different reasons. The first example is often called ‘the objective narrator’. It’s a really useful method for quickly giving the reader necessary information. Most writers will use it to give a wide-screen shot of the scene, before zooming in to the character’s thoughts and feelings, and then zooming out again.

Others will write the entire story in ‘deep point-of-view’, only ever revealing the character’s thoughts, feelings and impressions in a ‘stream-of-consciousness’ manner.

Of course, this method means a lot more investment from the reader – they need to figure out what’s going on with little help from the narrator.

The objective narrator is such a great tool for writers, but beware of over-using the device as it can create a coldness or a distance between reader and character. Slip into the deeper POV as often as you can without confusing the reader. One way to do this is to signal the change from the objective narrator to the deep point-of-view by moving from indirect discourse to free indirect discourse i.e. I wonder when she’ll be here, he thought. Damn, but I’ve missed that girl.

What is crucial, however, is that narrative distance must always be controlled. The author must choose how deep to go.

I hope this helps you!

all my best

Kate

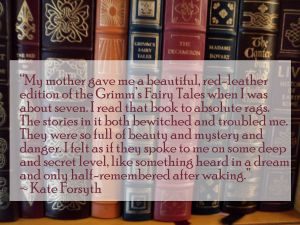

Kate Forsyth has been writing stories since she could first hold a pen, and has since sold more than a million copies worldwide. She has a Bachelor of Arts in Literature, a Master of Arts in Writing, and a Doctorate of Creative Arts in Fairy Tale Studies, and is an accredited master storyteller. She teaches creative writing at all levels at many different venues. Check out her Appearances Page to find out where she is next speaking.

If you found this post of interest you may enjoy

THE STORY DOCTOR: How do you know when your manuscript is finally finished?

THE STORY DOCTOR: How important is research in the writing process?

SPOTLIGHT: My notebook for THE WILD GIRL

Ask THE STORY DOCTOR to help you diagnose what's wrong with your story ...

Interview with Elizabeth Jane for the Historical Novel Society magazine

I read on your website that you started out wanting to tell the Rapunzel Story as a historical novel, as if it really happened (as part of your PhD?), until, as part of your research, came across Charlotte Rose de la Force who you describe as one of the 'most fascinating women ever forgotten by history,' and knew you had to write about her. Can you tell me about this process and at what point you decided the two stories must connect?

I began by wanting to rewrite ‘Rapunzel’. I’d been thinking about doing this since I was twelve, which is when I first tried to write a story based on the fairy tale. At that early age I knew I wanted to tell the story from the point of view of the girl locked in the tower. It was in my mid-teens when I realised I also wanted to tell part of the story from the point of view of the witch. So you can see it was a story I’d been interested in for a very long time.

I wrote many other books, but this idea still bothered me. One day I had an epiphany. I realised that I had been thinking of the book has a children’s fantasy, but that was why I had not been able to move forward with the idea. ‘Rapunzel’ was never meant as a children’s tale. It’s very dark and it’s very sexy. It’s a story of obsession, and madness, and desire, and resurrection, and it needed to be written for an adult audience. I also realised that I did not want to set it in a make-believe world. I wanted to set it in the real world, in our world, where girls are still kidnapped and locked up in attics all too often.

Once I realised I wanted to write the story as a historical novel for adults, I began thinking about the setting. Where and when would I set my Rapunzel retelling? I began to research the history of the tale, a decision that led me to undertaking my doctorate.

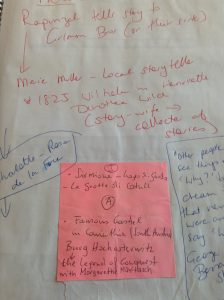

At the same time, I was playing with the idea of having a third narrative thread other than the stories of the maiden and the witch. I wanted the structure of the book to reflect the braid of impossibly long hair that is the most visually arresting motif of the story. I thought about the possibility of having one narrative thread set in contemporary times, with a girl locked away in a cellar, and I also thought about having the third narrative thread being someone – an old woman – telling the story to the Grimm brothers. I liked that idea, and so I began to research the background to the Grimm brothers’ fairy tales. It took me a long time, but eventually I discovered that the story I knew of as ‘Rapunzel’ was far older than the Grimms. I found the earliest known version had been written in the 1600s by Giambattista Basile, a man who was then working for the Venetian Republic. That set my imagination on fire, and so I began to envision the story set in late Renaissance Venice.

However, Basile’s story was not the story I knew. I wanted to retell the tale that had meant so much to me as a child. I had to track down how the story travelled from Venice to Germany, and how it changed along the way. Again it took me a long time, but eventually I discovered the story of Charlotte-Rose de Caumont de la Force, who wrote the version we know now of as ‘Rapunzel’. I knew at once I had to write about her – her life was full of drama and scandal and danger.

Regarding the viewpoint order in which you told the tale (brilliant, by the way), how did you determine what to reveal when? Did you know from the start that you would need the three viewpoints? Or did you write the three tales in full, chopping them up at a later point?

I knew I wanted three narrative viewpoints from the start, so I could weave them together like a braid. I wrote each strand separately, from the first word to the last word, as if I was writing three individual novels. I wrote Charlotte-Rose’s story first, with breaks to show where I would insert the other stories. Then I wrote Margherita’s story, from first word to last word, and wove it in to Charlotte-Rose’s story. Then I wrote my witch Selena’s story. My original plan had been to break it into sections and weave it through like the other two strands. However, I felt that would dissipate much of the power of her narrative, and so I changed my plan, and put Selena’s story, in its entirety, in the middle of the book. I call it the dark heart of the book.

You created such a plausible atmosphere of superstition and folk belief in 17th century France that the 'real magic' in the 16th century felt truly believable. How did you set out to achieve this?

Thank you so much! I always try and make the world of my story as vivid and alive as possible, so that you can really understand the forces working upon the characters. I read a great deal, including primary sources such as letters and memoirs, and I was particularly fascinated by the Affair of the Poisons – a scandal of murder and satanism which rocked the court of Louis XIV to its foundations.

When writing the sections set in Renaissance Venice, I read the work of an Italian historian, Carlo Ginzberg, who examined the Inquisition’s transcripts of 16th century witch trials. So many of the spells or practices in the book are ones which were actually recorded in Italy in the Renaissance.

How important is it to keep this element of the mysterious in fairy tale retellings?

It’s important for me! I think every creative artist brings their own passions and preoccupations to the task, and that is what makes their work so unique. I have always been fascinated by folklore and superstitions and the uncanny, and so my work reflects this interest.

How important do you think setting the story in a real time and place (as opposed to once-upon-a-time) were to achieving this?

For me, it was really important. I love the fantasy genre and many of my books are set far, far away, in make-believe lands. One of the great strengths of the fantasy genre is its quality of strangeness, and I love creating that type of world. However, with BITTER GREENS, I very much wanted to make it feel real, as if it had actually happened. I wanted to remind readers that the imprisonment of women against their wills is very much a cultural practice of our society … and it still happens. I did not want the escape hatch of magic, the sense that someone waved a wand and the impossible just happened. I wanted to find other reasons for the mysteries in the story.

Were the links to Titian art part of this decision? Or a happy coincidence?

Both!

I was working on Selena’s sections of the book and wanted to bring the world of Renaissance Venice vividly to life. I knew that I wanted her to be a courtesan, and that she had lived a remarkably long life without visible signs of ageing. I also knew, in the back of my mind, that I wanted to weave in something about Venetian art.

Then, one day, my son was doing a project on William Blake and I told him I had a book in my library that may be of help to him. I went and pulled the book on Blake out, and the book next to it fell out of the shelf and on to the floor. It was a book on Titian, and it had opened to a page showing colour plates of Titian’s paintings ‘Sacred & Profane Love’ and ‘Flora’, with a caption explaining how he used the same ideal of beauty in many of his paintings. Flicking though the book, I saw the same face appear again and again, and I remembered reading that Titian was thought to have been inspired by his mistress who had been a courtesan. I was absolutely electrified. I went racing to my study and started googling. Hours later, my son plaintively asked me if I had found the book on Blake … I had completely forgotten why I went into the library!

(Check out my Pinterest page on Titian to see all the paintings described in Bitter Greens)

Were the witches incantations a product of your imagination? Or did you find similar examples in historical sources? For example was bathing in the blood of virgins a real superstition that you utilised for your purposes? Or did you make it up? How important is it to the overall plausibility to find such connections?

I was inspired by Carlo Ginzberg’s work on 16th century Inquisition court transcripts, which contained a great deal of fascinating information on magical beliefs and superstitions of the time. I was also interested in other medieval accounts of witchcraft such as the Malleus Maleficarum. The idea of bathing in the blood of a virgin to preserve beauty is not new. It was a common belief of the time. The Hungarian Countess Erzsébet Báthory was thought to have murdered hundreds of girls in the early 1600s for this purpose. I always like to have the magic in my stories deeply rooted in the real. It makes it feel more possible.

How important do you think a surprise ending is to a fairy tale re-telling? How important is it to have a hitherto unexplored perspective?

I think surprise is the magic ingredient of all good storytelling. I am always thinking to myself, how can I best surprise the reader? I think this is even more important in a fairy-tale retelling, because the story’s structure and motifs are so familiar to most readers. ‘Rapunzel’ is one of the best known tales in the world, and so the challenge for me was to transform it into a compelling, suspenseful and unexpected reading experience.

You worked with a translator? Was this frustrating? Did you have a sense that if you could have just read the materials yourself you might have uncovered more? What did you tell the translator you were looking for?

My translator translated every single word for me, so there was no need for me to worry about missing things. It was a massive job. Sylvie translated some of Charlotte-Rose de la Force’s fairy tales that had never before been translated, plus a

brief autobiographical sketch she had written, as well as a biography of Charlotte-Rose written by a French academic. She also communicated for me with some French fairy tale experts, and with the Comte de Sabran-Pontevès, a descendant of the La Force family who still lives in the Chateau de Cazeneuve where Charlotte-Rose grew up. Then, when I went to France and visited the Chateau, I hired another translator to go with me to help me communicate with the Comte (he gave me a private tour of the chateau – it was absolutely amazing! I saw Charlotte-Rose’s pram and her baptismal records which proved her birth age).

What would you say were the main themes of your novel? If I were to take a guess I would say redemption - which, I believe, is an element of the de la Force version of the tale that appealed to you.

Yes, I think it is all about redemption. The ‘Rapunzel’ fairy tale has its roots in ancient nature myths. All the characters in it – maiden, prince, crone - journey through death and darkness into light and rebirth again. It’s extraordinarily beautiful and powerful.

Was this part of your decision to give the witch a viewpoint - indeed, to create an empathy for her in the reader's minds?

Yes, this was an important aspect of the tale for me.

Through her life, and that of Charlotte-Rose, did you also want to show the limited options for women apart from the church or marriage?

This was certainly important for me too. I always think that I am living the life Charlotte-Rose dreamed of. I was free to choose who to love, and free to write as I please. Its important women never forget how far we have come, and how hard the battle has been.

In Mirror Mirror (Bernheimer, Kate, Anchor Books, 2002), Margaret Atwood describes an antipathy for 'pinkly illustrated versions of Cinderella or Sleeping Beauty stories whose plots were dependant on female servility, immobility or even stupor, and on princely rescue.' I believe one of the reasons you liked de la Force's version of the Rapunzel tale is because the woman in the tower takes a more active role in her own redemption. Indeed, in Bitter Greens, Lucio tells her Margherita, that she must look in her heart and find a way to break the spell. Can you talk to me about your reasoning here? Is your novel a conscious attempt to fight against the helpless princess stereotype?

It always makes me cross when people call Rapunzel the ‘passive princess waiting patiently for her prince’. She is not a princess, she does not wait patiently but rather sings with all her heart and soul and so draws the prince to her, and she is the one that saves the prince, not the other way around. She is a mythic figure of feminine power, who frees herself and then heals the blinded eyes of the prince. It is true that she is held in stasis and immobility in the first part of the story, but never forget that she escapes her tower at the end. That is the whole point of the story.

As you know, the fairy tale was an oral storytelling tradition long before it ever became a literary form, with each teller altering the tale for their own purposes. Do you see your own re-telling of Rapunzel as contributing to this tradition? Would your twenty first century message be that women hold the key to their own destiny? How does Charlotte-Rose de la Force's life further illustrate this theme?

Yes, I like to think of myself as being the latest in a long chain of storytellers, both oral and literary, who have told and retold the tale from the very beginning of human history. I imagine the story as a flame, passed from hand to hand, casting light into the world.

And remember that it is not only women who are held captive by the metaphorical towers of society. Men are too. Fairy tales are a window into the human psyche, and hold wisdom for us all.

A little question aside from fairy tales ... In the chapter A Mere Bagatelle you have a delightful argument between Michel Baron and Charlotte-Rose about their writing. Some of the memorable lines are: 'All these disguises duels and abductions... All these desperate love affairs. And you wish me to take you seriously.' 'I like disguises and duels... At least something happens in my stories.' 'At least my plays are about something.' Etc... How does this describe your own working life? Where you sit on the literary spectrum? Like Charlotte-Rose do you see yourself as an intelligent female writer of fantasy/historical fiction who has a literary turn of phrase yet also wants to tell a good story, with themes like love and redemption, that women in particular will enjoy?

I’m glad you enjoyed that scene! I have let Charlotte-Rose speak for me there. I too like stories in which things happen, and I too think that stories about love express one of the most universal human longings. Like Charlotte-Rose, I relish language, for its beauty, and for its ability to help us articulate ideas and emotions, and connect with other humans. I love storytelling, and am not interested in books that fail to tell a good story. Yet I want to think as well as feel, and so I love books that are full of big ideas, where I learn new things, and come to understand something that has always eluded me before. I see no reason why a page-turning, compelling story cannot be well-written too!

Sometimes a book can change your life.

The Diary of Anne Frank was that kind of book for me.

I read it when I was twelve years old. I can still remember the awful shock of reaching the end, and finding out that Anne did not escape her attic, that she died in Bergen-Belsen when she was only a few years older than I was.

I had never read a book like it before. It felt like I had been punched hard in the solar plexus. I could not breathe, I could not cry. My very heart felt bruised.

Anne Frank

I began to write my own diary a few days later. Anne Frank had written hers as a series of letters addressed to an imaginary friend named Kitty. I did the same, but addressed mine to “Carrie”. The first entry was written on 15/8/1978 and began ‘Dear Diary, your name is now Carrie. You’ll be my confidant and my port in which to lay my head and my poor worn-out hopes, thoughts and ambitions …’

I have written in my diary nearly every day since. That is thirty-seven years of consecutive diary writing, much more than the two years so tragically given to Anne Frank.

Her diary also sparked in me a lifelong fascination with Hitler, and those few brave people who tried their best to resist Nazism. I began to collect a library of books to do with the Second World War, many of them first-hand accounts and memoirs. I was particularly interested in stories of ordinary people who found within themselves extraordinary courage and strength. I knew that one day I would try and write a novel about someone like Anne Frank.

The years passed, and I wrote a great many books. More than thirty-five at last count. My books range from picture books to poetry, and from heroic fantasy for children to historical novels for adults. I have written books set in Renaissance Venice and at the court of the Sun King in Versailles, in the English Civil War and in the perilous reign of Mary, Queen of Scots, in the Napoleonic Wars, and in worlds of my own imagining. Yet the Second World War never loosened its hold on my imagination. I continued to read as many books as I could find set at that period, and to continue to think about writing one of my own.

Fairy tales are another long-held passion of mine. I have just completed a doctorate in the subject, and many of my novels have fairy tale motifs and metaphors entwined through their stories.

The Wild Girl tells the story of the forbidden romance between Wilhelm Grimm and Dortchen Wild, the young woman who told him many of the world’s most beloved ‘wonder tales’. She told him stories like ‘Hansel and Gretel’, ‘Rumpelstiltskin’, ‘The Frog King’, ‘Six Swans’, ‘The Elves and the Shoemaker’, and ‘The Singing, Springing Lark,’ a beautiful variant on the tale we know as ‘The Beauty and the Beast’.

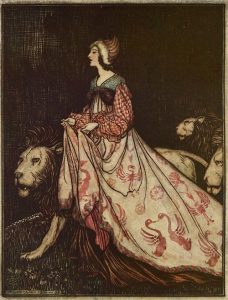

Arthur Rackham's illustration for 'The Singing, Springing Lark'

In this story, the father catches a lark, rather than stealing a rose, and the beast of the tale is a lion by day and a man by night (an arrangement which I always thought might have its compensations). The greatest difference, however, is the ending. In Dortchen Wild’s tale, the heroine must follow a trail of blood and white feathers her lover leaves behind him, and then outwit the enchantress who first cast the curse upon him. The heroine is given three gifts to help her: a dress as golden as the sun, another as silver as the moon, and a griffin on which to escape.

Writing a novel always throws up many unexpected ideas as well as unforeseen problems, and The Wild Girl was no exception. Taking place over twenty years, and told from the point of view of a young woman forgotten by history, The Wild Girl was very research-intensive indeed. And, for a long while, I did not have a strong sense of the narrative structure. I knew I wanted to retell one of Dortchen’s stories in some way; I did not yet know how.

While researching the Grimm Brothers, I was distressed to learn their tales had been banned in Germany after the Second World War, as part of the Allies’ Denazification program. Hitler had loved the Grimm Brothers’ fairy tales and had recommended all German households have a copy on their shelves. I went to bed that night troubled and upset. I loved the Grimm tales too. In times of darkness and fear, they had given me light and comfort. Yet I had always hated the Nazis and all they stood for, including their burning of books.

I could not get to sleep that night, my mind in turmoil. Eventually I got up and found myself a novel to read. I chose an old World War II thriller, about the Danish resistance to the Nazis. I read the whole book through, finally going to sleep long after midnight. Just before I fell asleep, I thought again about the novel I was struggling to write and about the beautiful tales Dortchen Wild had told Wilhelm Grimm. I said to myself: “Trust in the universe. The answer will come.”

The next morning, as I drifted in that hypnopompic state between sleeping and waking, an image rose up in my mind’s eye. I saw a beautiful young woman, wearing a dress as golden as the sun, singing in a vast dark hall. Her audience were German soldiers in black SS uniforms. I knew instinctively that she was some kind of spy, or resistance fighter, and also that she was German herself.

I wrote in my diary that day, Monday 3rd October 2011: ‘I couldn’t sleep last night for worrying about Wild Girl … I need something new, strange, unexpected, surprising … I woke this morning and lay in that dim borderland between awake and asleep, that place of creative dreaming, and the idea came to me – why not have the secondary tale set in WWII … perhaps she has to flee and live wild in the woods – or joins the German Resistance - & she carries everywhere a copy of the Grimm fairy tales, as a kind of talisman … it feels good, it feels right, it feels hard and scary – but absolutely seems it have some kind of power to it …’

My unconscious mind had put together two very different desires – wanting to write a novel about resistance to the Nazis and wanting to retell one of Dortchen Wild’s fairy tales – and come up with something quite unexpected.

That was the beginning of my novel The Beast’s Garden, a retelling of the Grimms’ version of ‘Beauty and the Beast’, set in the German underground resistance to Hitler.

That vision, that not-quite-a-dream, was the beginning of an extraordinary journey of discovery for me. At first, I thought that this story of courage and resistance would be the second narrative strand in The Wild Girl. Slowly I came to realise it was a novel in its own right. I had to put the idea aside as I wrote The Wild Girl and finished my doctorate in fairy tale studies. The idea would not leave me alone, however. I began to read as much as I could about the German Resistance.

I discovered, rather to my surprise, that many Germans abhorred the Nazis and risked their lives to stand against Hitler. I read about the Swing Kids who played jazz and danced swing in basements and cellars, despite the threat of arrest. The White Rose group of students in Munich printed leaflets calling the German people to rise up against the Third Reich. The Edelweiss Pirates in Cologne did battle with the Hitler Youth and hid deserters from the army. The Baum group in Berlin blew up one of Goebbels’ exhibitions. Other resisters smuggled Jews out of Germany, or hid them in their houses and gardens. Most of them paid for their defiance with their lives.

One of the most successful groups of resisters was based in Berlin. The Gestapo called them the Red Orchestra. They called themselves the Zirkel, which simply means circle. Their members were writers, actors, journalists, musicians and sculptors. Their leaders were a Luftwaffe officer called Harro Schulze-Boysen, his young aristocratic wife Libertas, and their friends Arvid and Mildred Harnack. Mildred would earn the terrible distinction of being the only American woman to be executed by the Third Reich.

Harro & Libertas Schulze-Boysen, who were both executed for their resistance to the Third Reich

I imagined a young German woman (the Beauty of the tale) who marries a Nazi officer (the Beast) in order to save her father. But secretly Ava helps her Jewish friends whever she can. One day she meets Libertas, and is drawn into the dangerous world of the underground resistance. Living a double life, she must spy on her husband Leo in order to help save whom she can. Gradually she comes to suspect her husband is himself involved in a plot to assassinate Hitler. When the plot fails, Ava must risk everything to try and save her husband from a cruel traitor’s death.

The Beast’s Garden was in many ways the most difficult book I have ever written. I found the research utterly harrowing. For months, every day was spent reading about Hitler, about the Gestapo, about the Holocaust. I wrote the first draft entirely in first person, as if it was a diary or a memoir. But then I found it was too limiting, trying to tell such a big story from just one person’s point of view. I rewrote the entire book, in just six weeks, from a number of different points of view, including that of a Jewish girl in hiding.

On Thursday 12 February 2015, I wrote in my diary: ‘I finished the novel last night, at 1am … and could not sleep afterwards … very tired now, but oh so happy …’

The Beast’s Garden is my paean to all those ordinary people who found such extraordinary courage and strength of spirit within them during the dark days of the Third Reich, including, of course, Anne Frank and the people who hid her and her family.

You can read more about my liminal dreaming here and more about my research books for THE BEAST'S GARDEN here

PLEASE LEAVE A COMMENT - I LOVE TO KNOW WHAT YOU THINK!

We live in soul-harrowing times.

So much anxiety, so much terror. Sometimes I feel as if my heart is being broken every time I watch the news. Hatred, violence, bigotry and sadism seem to dominate our news screens and streams. I fear for my children and for our world.

A few years ago, I wrote a novel set in the underground resistance to Hitler in Nazi Germany.

I spent months researching World War II, its causes and consequences, its horror and heroism. I had been fascinated by the period ever since I was a little girl and read 'The Diary of Anne Frank' for the first time. As I grew up, I read many hundreds of books about resistance and defiance and have long wanted to write one. At last this desire became urgent. It is important, I thought, to remember the past so we can do not make the same terrible mistakes again.

The whole time I was writing 'The Beast's Garden', I kept thinking to myself - what would I do if it was me?

My heroine Ava is not sent to spy school or taught how to shoot a machine gun. She is just an ordinary young woman, living in extraordinary times. She lives with her father and her sisters, she wants to be a singer, she hopes one day to fall in love. But Ava lives in Berlin in 1938. The German people had just voted Hitler into power, hoping he will make good on his promises of more work and new political stability. Many people think Hitler is just a clown, or a bumbling fool. Sure, he shouts a lot and his followers seem like thugs. But how much harm could one man do?

What awful irony.

The Beast's Garden begins on Kristallnacht with the words: "Ava fell in love the night the Nazis first showed their true faces to the world."

It is a novel about the importance of courage and resistance, and the importance of kindness and compassion. It tells the true and largely untold story of the German underground resistance who paid for their defiance with their lives.

I hope that none of us ever have to see the kind of darkness and horror that saw Anne Frank die in a concentration camp.

My writing of The Beast's Garden was, in a way, a call to arms. Please, let us all stand up against hatred and bigotry and racism and cruelty in every way we can. Let's write and create art and protest and point out the terrible mistakes of the past again and again, until we learn from them. Please.

I have always been a great believer in serendipity. It's as if the universe sees a lacking, or a longing in me, and nudges something I need towards me.

This time serendipity has brought about the most magical conjunction of events, which is going to result in a most beautiful book.

As you probably know, I have long been interested in long-forgotten fairytales and fairytale tellers, and many of my books have been inspired by a desire to save them for obscurity.

After I finished my Doctorate of Creative Studies in fairy-tale studies, I wanted to buy myself something really special to celebrate. A twitter friend posted the most beautiful picture of a fairy-tale-inspired art work by Lorena Carrington, and I clicked the link which took me to her blog, The Bone Lantern. I read some of her blog posts and looked at some of her exquisite photographic art, and just fell in love with them. She must be a kindred spirit, I thought, to produce such beautiful work. I emailed her to see if I could buy one of her pieces (& ended up being this gorgeous print - it now hangs in my hallway).

I also asked her if I could interview her for my blog, always being interested in profiling the work of other creative artists.

We emailed back and forth, sharing our love of art and fairy-tales and gardens and books, and finding out we had so much in common. She told me that she dreamed of putting together a gorgeously illustrated anthology of little-known fairy tales with strong, brave heroines, and had begun illustrating a few of her favourites already. I told her that I was interested in doing the same thing. Perhaps we should do one together, we thought.

Both of us were busy with other projects but, whenever we could, we tossed around ideas and stories, and played with images and possibilities. Together we built up an idea of what we'd like to do ... maybe, one day.

I was hard at work researching & writing my novel about the Pre-Raphaelites but, as soon as I had delivered the manuscript to my publishers, I thought again of this idea of creating something with Lorena.

I reached out to the universe (i.e. I posted on Facebook):

One day I'd like to write #fairytale retellings of little-known tales with brave, clever heroines for teenage girls to read. Would anyone like to publish stories like that?

And the universe sent me Monique Mulligan of Serenity Press, who replied: Yes!

And so I'm thrilled to announce that Serenity Press will be publishing our fairytale collection Vasilisa the Wise & Other Tales of Brave Girls in 2018.

I will be re-telling seven extraordinary little-known fairy-tales (including one written by Charlotte-Rose de la Force, the true-life heroine of my novel Bitter Greens), and Lorena will be illustrating them with her beautiful art.

Never tell me magic does not happen!

For almost a year I have been working on a novel called The Blue Rose.

It tells the story of Viviane de Ravoisier, the daughter of a French marquis, and David Stronach, a Welsh gardener who travels to her chateau in Brittany to design and plant an English-style garden. The two fall in love, but their passion is forbidden. David is driven away and Viviane is married against her will to a duc. She is taken to the palace of Versailles where she witnesses the early days of the French Revolution. Through her eyes, I tell the story of the fall of the Bastille, the abolition of the nobility, and the beginning of the Terror.

I imagine the Chateau de Belisima-sur-le-lac looking a little like this chateau in Brittany, the Château de Trécesson:

I first discovered this chateau when someone posted a picture of it on Facebook, wondering what the chateau was called. It was so like what I imagined Viviane's home looking like, I went and searched on the internet until I located it and it has been my desktop picture ever since.

I have a very visual imagination and so I am always printing out pictures and sticking them in my notebooks, or pinning them on Pinterest (you can check out all the pictures on my Pinterest page if you like.)

I also like to collect small artefacts that help inspire my imagination.

The first is a small miniature of a 18th century French noblewoman that I bought on Etsy. It's the most exquisite little painting, and it has work dits way into the story as a miniature of Viviane's mother, who died the day she was born.

My other treasure, I found in an old antique shop in France when I was there two years ago researching this book.

It is a huge old key. The man in the antique shop told me that it was the key to a chateau that had been burned during the french revolution. The key was found in the chateau well 270 years later. No-one knows who threw it in the well, or why. This story really intrigued me and so I bought the key, and it now hangs on my wall.

This anecdote too has worked its way into the story.

This week, I finished Part II of The Blue Rose and reached the halfway point at 60,000 words in total.

My action now moves from France to a ship sailing around the world to China.

I plan to go to China with my son in mid-May. Maybe I will find some fascinating artefact there that will inspire me anew. I hope so!

The National Gallery of Australia has just announced a major exhibition of Pre-Raphaelite art, 'Love & Desire', will open in mid-December. It's bringing out many of the Tate's masterpieces for the very first time. This is a chance for Australians to discover the extraordinary luminous art of this circle of passionate rebellious mid-Victorian artists, which I have loved all my love and which inspired my novel, Beauty in Thorns.

Beauty in Thorns is an historical novel for adults which tells the astonishing true story behind the famous 'Sleeping Beauty' painting by the Pre-Raphaelite artist Sir Edward Coley Burne-Jones. Told in the voices of four very different women, Beauty in Thorns is a story of love, desire, art, and awakenings of all kinds.

Burne-Jones painted the Sleeping Beauty fairy tale many times over the forty-odd years of his career:

In May 1856, Burne-Jones drew a pencil sketch of his betrothed, Georgie Macdonald, as the Sleeping Beauty to amuse her little sister Louie on her birthday. He was 23 years old and Georgie was sixteen. I believe this is the sketch, though it has not been officially confirmed.

In 1862, Burne-Jones designed a series of 'Sleeping Beauty' tiles for a client of the Morris & Co decorating firm, of which he was a partner. The princess looks very much like Lizzie Siddal, who had died a few months earlier of a laudanum overdose, and the prince kneeling to kiss her awake looks very much like her grieving widower Dante Gabriel Rossetti. The peacock (featured on the wall of the boudoir) is a symbol of immortality and rebirth. This tile is one of nine in a sequence that begins with the baby in her cradle and ends with the marriage of the prince and princess. The tiles can be seen at the V&A Museum in Kensington.

In the 1870s, Burne-Jones had a tempestuous affair with one of his models, the sculptor Maria Zambaco, and he painted a very sensual version of Sleeping Beauty with his mistress modelling as the princess. The affair ended badly, with Maria attempting to drown herself in Regent's Canal. At one point, Ned planned to run away with Maria but he ended returning to his wife and family so they would not be besmirched by the scandal.

This painting - now in Puerto Rico - was the final in a sequence of three paintings that showed the prince in the briar wood, the king and his councillors asleep in the council chamber, and the princess asleep with her maids.

This beautiful drawing is a chalk study of his daughter Margaret that Burne-Jones made in 1881, when he was planning another sequence of painting inspired by the fairytale. Margaret was then fifteen, the age of the princess in the story.

And this exquisite painting of his daughter Margaret as Sleeping Beauty was created by Burne-Jones in 1884-1887, as the final in a sequence of four enormous painting which now hang in Buscot Park, in Oxfordshire. Margaret was aged in her late teens and early twenties, and had fallen in love with a young poet and scholar named John William Mackail, much to her father's distress.

The four paintings - called 'The Legend of Briar Rose' - caused an absolute sensation when they were first exhibited in 1890, with queues of carriages along Bond Street and crowds of people returning again and again to view them. Burne-Jones sold the quartet of painting for fifteen thousand guineas, the most money a British artist had ever been paid, and he was subsequently knighted by the Queen.

His final painting is a small circle, entitled 'Wake Dearest' which he painted for his ever-loving and faithful wife Georgie in the final year of his life (1898). I believe she was the model for the princess. This tiny masterpiece - along with 37 other tiny glowing circles - were left to Georgie in his will, and later published as 'The Flower Book'.

My novel Beauty in Thorns tells the story behind the creation of these exquisite drawings and paintings - a story of love, betrayal, heartbreak, death, and awakening of all kinds.

The Blurb (From Goodreads):

The first time Julia Beckett saw Greywethers she was only five, but she knew that it was her house. And now that she’s at last become its owner, she suspects that she was drawn there for a reason.

As if Greywethers were a portal between worlds, she finds herself transported into seventeenth-century England, becoming Mariana, a young woman struggling against danger and treachery, and battling a forbidden love.

Each time Julia travels back, she becomes more enthralled with the past...until she realizes Mariana’s life is threatening to eclipse her own, and she must find a way to lay the past to rest or lose the chance for happiness in her own time.

My Thoughts:

When Julia Beckett was a little girl, she pointed at an old house in an English village and said, with great conviction, ‘that’s my house.’ Twenty-five years later, she buys the house and moves to live there. Almost immediately, she finds herself slipping back in time and into the life of Mariana, a young woman in the Restoration era. The slippages are involuntary, astoundingly vivid, and dangerous. Julia is not aware of what her body is doing in her own time, and her life as Mariana becomes increasingly urgent and important to her. She falls in love with the 16th century lord of the manor, Richard de Mornay, and is haunted by the conviction that something terrible happened to him. Gradually, her two lives begin to mesh and Julia discovers why she was drawn to live her past life over again.

A gentle and beguiling story of romance, betrayal, and reincarnation, Mariana has an old-fashioned feeling to it. At one point, a character says, ‘What rot!’ which is what characters always say in my beloved old schoolgirl books from the 1930s. Julia’s brother is a vicar, which somehow adds to the Agatha-Christie-type atmosphere of this small English village, and the only sex scene happens offstage. The book was published in 1994, which is after the invention of the internet, but Julia’s brother must go to the library to dig up tales of reincarnation and past life flashbacks. So it’s difficult to pinpoint when the modern-day sections are set. I don’t mind this at all. I love books written in, or set during, the 1930s and 40s, and the book reminds me of time travel books I loved as a child, like Tom’s Midnight Garden by Philippa Pierce and A Traveller in Time by Alison Uttley.

In a way, the timelessness of the story makes it even more enjoyable. And I can’t help wishing I could buy an old house in an English village, and discover I once lived there before …

You might also like to read my review of Season of Storm by Susannah Kearsley:

https://kateforsyth.com.au/what-katie-read/vintage-book-review-season-of-storm-by-susannah-kearsley

As many of you will know, I have spent the past few years researching and writing about the fascinating lives of some of the women in the Pre-Raphaelite sisterhood for my novel Beauty in Thorns.

BEAUTY IN THORNS is an historical novel for adults which tells the story of the tangled desires behind the famous painting ‘The Legend of Briar Rose’ by the Pre-Raphaelite artist Edward Burne-Jones.

Four very different women tell the story: the wives, mistresses, and muses of the Pre-Raphaelites, Georgie Macdonald, Lizzie Siddal, Jane Burden, and Margaret Burne-Jones, the artist’s beloved daughter.

The Pre-Raphaelites were a collection of daring young artists who outraged Victorian society with their avant-garde paintings, their passionate affairs, and their scandalous behaviour.

Dante Gabriel Rossetti was one of the founders of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood in 1848. His work and ideals inspired Edward Burne-Jones and his friend William Morris to create their own art, and with it, to try to change the world.

The ‘Sleeping Beauty’ fairy tale haunted Burne-Jones’s imagination, and he painted it many times over the course of thirty years, culminating in an extraordinary quartet of paintings that were greeted by the public with ‘enthusiasm amounting to ecstasy’ in 1890. It was bought for 15,000 guineas, the largest amount ever paid for an artwork in Britain, and Burne-Jones was consequently knighted in 1893.

Burne-Jones and his friends drew together an extraordinary group of young women who all struggled in their different ways to live and love and create as freely.

In chronological order of birth:

Lizzie Siddal (b. 1829)

Discovered working in a milliner’s shop, Lizzie became one of the most famous faces of the early Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, modelling for paintings by Rossetti and Millais (she is his famous Ophelia). She and Rossetti began a passionate and turbulent affair. Heart-broken by his infidelities, Lizzie took refuge in laudanum. As she lay dying, Rossetti promised to marry her if she would only recover. They were married in 1860, but the birth of a dead child caused Lizzie to sink further into depression and addiction. She died of an overdose in 1862. Rossetti famously buried his poems with her but later had her exhumed to retrieve the manuscript.

Jane Burden (b. 1839)

Jane was discovered by Rossetti and Burne-Jones in Oxford, and became one of their most striking and famous models. She married William Morris, but began a scandalous affair with Rossetti after the death of Lizzie Siddal. She had two daughters, Jenny and May. Her eldest suffered from epilepsy, then thought a most shameful disease.

Georgie Macdonald (b. 1840)

The daughter of a God-fearing Methodist minister, Georgie met Ned Burne-Jones when she was ten. He awoke her to a new world of art and poetry and beauty, and she shared with him her favourite fairy tale “Briar Rose”, which inspire him to create some of his most beautiful paintings. Georgie married Burne-Jones at the age of nineteen, after a four-year engagement.

The early years of their marriage was idyllic, but in 1864 Georgie contracted scarlet fever, which brought on the premature birth of her second child, who consequently died. Her third child – a daughter named Margaret – was born in 1866, the same year as Burne-Jones began a passionate and ultimately calamitous affair with his model, the beautiful and fiery Maria Zambaco.

Margaret Burne-Jones (b. 1866)

The third child born to Edward and Georgie Burne-Jones, after the tragic death of their second son. She was a shy and reserved child remarkable for her beauty. As she grew, she found herself in demand as a model for the Pre-Raphaelites, but struggled with the unwanted attention. In 1888, she fell in love with the Scottish writer, John William Mackail, but her father refused to countenance their marriage. He was obsessively working on his painting of her as the sleeping princess in "The Legend of Briar Rose" series, and was afraid of losing his muse. Margaret had to find the strength to defy her father and marry the man she loved.

The Pre-Raphaelite circle also included Effie Millais, Fanny Cornforth, Christina Rossetti, May Morris, Mary de Morgan, and many others who I wish I could have included in my novel. maybe one day I'll write something about them too ....

PLEASE LEAVE A COMMENT - I LOVE TO KNOW WHAT YOU THINK!