The Blue Rose tells the story of an impossible love between a marquis’s daughter and a gardener, and was inspired by a true quest for a blood-red rose that blooms even in winter. It moves from France during the 'Terror' of the French Revolution to Imperial China, a mysterious and scarcely discovered land of mandarins with long curving fingernails and concubines with bound feet.

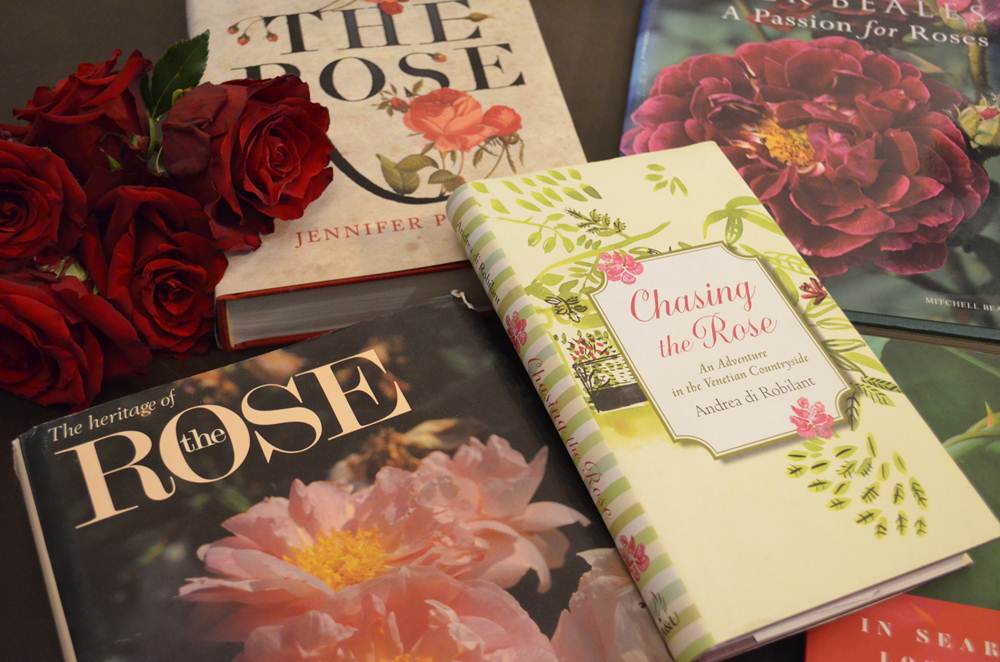

I first got the idea for The Blue Rose in March 2015 when I read a memoir called Chasing the Rose by the Italian journalist Andrea di Robilant, about his quest for a rare rose.

In one passage he wrote: ‘In 1792, Gilbert Slater, a nurseryman from Knotts Green, Leyton, introduced a dark, rich crimson rose known in China as Yue Yue Hong, or “Monthly Crimson”. Europeans had never seen a rose of that colour (called pigeon's blood). The cultivar, which became known as “Slater's Crimson China”, quickly spread to France ... It became the ancestor of many of the red roses we have today ...’

How fascinating, I thought. Surely Europe had red roses before 1792?

And then, I thought ... 1792. That was right at the beginning of the French Revolution. That was when the Tuileries was stormed and Princesse de Lamballe’s head was paraded around on a pike.

Andrea di Robilant went upon to say: ‘Around that time ... Sir George Staunton, a young diplomat and enthusiastic gardener, travelled to China as secretary to Lord Macartney. Taking time off from his embassy, he went looking for roses and found a lovely re-flowering silvery pink specimen in a Canton nursery, which he shipped to Sir Joseph Banks, the powerful director of the Royal Botanic Gardens in Kew.’

I had read about the Macartney Embassy before. Britain wished to open up trade with China, which was still closed to the West. Britain was importing tea and silk and Chinese porcelain in great quantities, but China was buying nothing in return. So, in 1793, Lord Macartney and his entourage travelled to Peking to meet with the Emperor. At that time, it was Chinese custom to kowtow before the Emperor.

Lord Macartney, as a representative of King George III, refused to kowtow. The Emperor refused to open trade.

I knew about this failed ambassadorial journey because it was one of the things which led to the Opium Wars between Britain and China in the 19th century. I did not know, however, that the British had brought roses back with them.

I was so interested by this story that I went browsing amongst the many books on roses I have on my shelves (I've always been a rose fancier.) I discovered that the introduction of the China roses to the West at the end of the eighteenth century revolutionised rose cultivation.

For the first time, roses could be grown that had more than one flush of blossoms. And for the first time Europeans could grow a rose that was truly red, long considered the symbol of passionate love.

I also eventually discovered that, contrary to popular belief, Gilbert Slater was not responsible for bringing the rose now called ‘Rosa Chinensis Semperflorens’ back from China. He certainly sent his gardener, James Main, to Canton; however, as I discovered when I read James Main’s memoirs, none of his plant specimens survived the long journey home. James Main went on to write, in ‘Paxton’s Horticultural Register’ (May 1835), that Rosa Semperflorens was not ever among Slater’s botanical collections.

So it is a mystery how the ever-blowing red rose of China (as it was romantically called) made it back to England. Examining Sir George Staunton’s record of his journey to China, I discovered that the embassy gardeners – one named John Haxton and one named David Stronach – had found not one, but two, rose specimens in Canton. Was it possible, I wondered, that the second rose found was ‘Yue Yue Hong’, the blood-red repeat-flowering rose that is the ancestor of all our red roses today? If so, why was it hybridised in France?

Historical novelists love the gaps and holes in historical records, because that is where the imagination can play.

My exploration of the mystery of the ever-blowing red rose led me to France and to China, and back in time to the late 18th century and all the bloody turmoil of the French Revolution.

But why did I call my book The Blue Rose when it is inspired by the quest for a rose the colour of blood?

You will just need to read the novel to find out!

BUY AUDIO BOOKS