Kate Forsyth examines Tolkien’s famous lecture on Fairy Tales and how it helped him to invent the genre of fantasy as we know it today

The genre of fiction that we know as ‘fantasy’ was born on 8 March 1939, on a cold, sleeting spring evening at the University of St Andrews on the east coast of Fife, Scotland. A room full of bespectacled students with bored expressions sat in rows, wrapped in their academic robes, as a thin, ascetic-looking middle-aged lecturer from Oxford mounted the podium.

Up until then, the Andrew Lang lectures at St Andrews University had borne such edifying titles as ‘Andrew Lang’s Word for Homer’, ‘Andrew Lang as Historian’, and ‘Lang, Lockhart and Biography’. So a stir of surprise and amusement ran over the crowd when the guest lecturer announced, ‘I propose to speak about fairy tales, though I am aware that this is a rash adventure.’

A few students who had already slipped into slumber awoke in surprise. ‘What? What’s going on?’ one mumbled, blinking around.

‘He’s going to talk about bleeding fairy tales,’ his neighbour told him. ‘Go back to sleep.’[1]

‘Faerie is a perilous land, and in it are pitfalls for the unwary and dungeons for the overbold,’ the lecturer continued. ‘And overbold I may be accounted, for though I have been a lover of fairy stories since I learned to read, and have at times thought about them, I have not studied them professionally. I have been hardly more than a wandering explorer (or trespasser) in the land, full of wonder but not of information.’

The lecturer paused and looked around the room, which had settled down into silence again. He was a rather ordinary-looking man, with a high forehead and a long nose, but his voice was deep and compelling, and he had a way of investing certain words with drama and power.

‘The realm of fairy story is wide and deep and high and filled with many things,’ he went on. ‘All manner of beasts and birds are found there; shoreless seas and stars uncounted; beauty that is an enchantment, and an ever-present peril; both joy and sorrow as sharp as swords.’

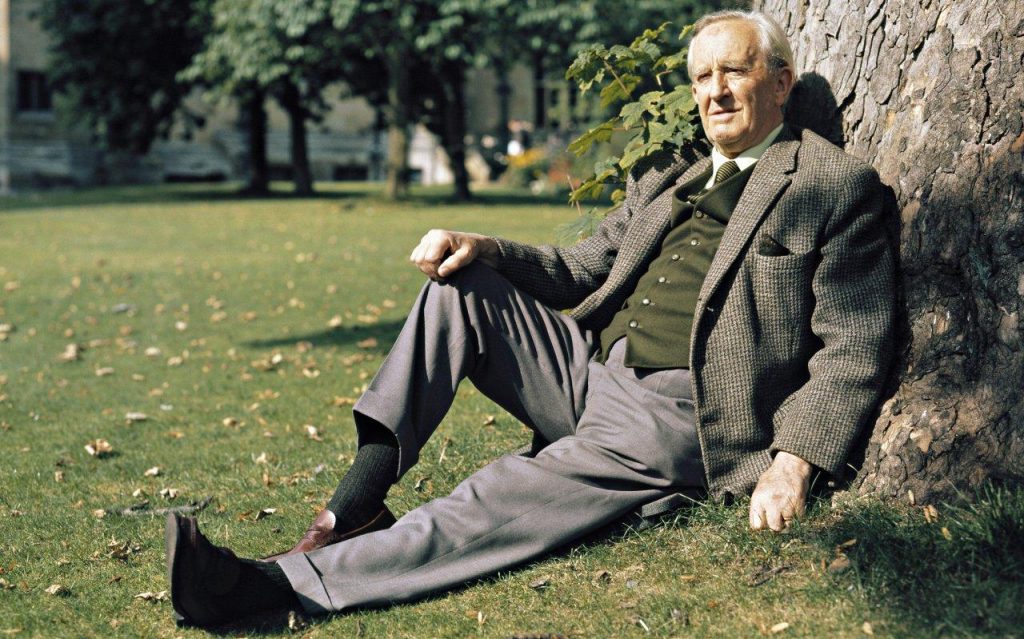

The Oxford don on the podium that day was, of course, John Ronald Reuel Tolkien, known as ‘Tollers’ to his friends and ‘Ronald’ to his wife. He was 37 years old, married, with three sons and a daughter, and Professor of Anglo-Saxon at Oxford University. He had published a children’s book two years earlier, The Hobbit, which had sold out its first print run of 1,500 books in two months and earned him a nomination for the Carnegie Medal but had been dismissed by his colleagues with ‘surprise and a little pity’.[2]

In the spring of 1939, the world was desperately hoping to avoid another cataclysmic war like the one that had torn Europe apart 20 years earlier. Adolf Hitler had been the Chancellor of Germany for six years and had already annexed Austria and Czechoslovakia. He had also already begun the persecution of Jews, culminating in the vicious Kristallnacht of November 1938, when thousands of synagogues were burnt, hundreds died, and 30,000 Jews were rounded up and sent to concentration camps.

Many of the students in the lecture room that day must have wondered why Professor Tolkien was wasting his time and theirs by rambling on about fairy tales when the newspapers were filled with images of marching armies, hunger strikes and bomb explosions. They were not to know that they were present at what would become one of the most famous university lectures ever given.

Tolkien was a philologist, which quite simply means he was a lover of words. He was interested in their history, their meaning and their power. In his lecture on fairy stories, Tolkien said, ‘It was in fairy stories that I first divined the potency of words, and the wonder of things, such as stone, and wood, and iron; tree and grass; house and fire; bread and wine.’

He wanted a word that would describe stories that had all the atmosphere and mystery and beauty of fairy tales, without the implication of those stories being childish or sentimental or patronising – what Tolkien called Pigwiggenry.

‘I propose . . . to use Fantasy for this purpose,’ he told his bewildered audience. The word combined both the idea of ‘fancy’, or the imagination, and the fantastic, what Tolkien called ‘the freedom from the domination of observed “fact”’.

At that moment, fantasy as we know it was born.

Of course, like any newborn baby, its genealogical chart stretches far back beyond human records. I like to argue that fantasy is the oldest form of narrative art. As long as humans have had language, we have been telling stories of heroes and quests and battles between good and evil. As Joseph Campbell famously showed in The Hero with a Thousand Faces, all human cultures have their story cycle - myths and legends and folktales and oral history - populated with the archetypal figures of the Reluctant Hero and the Wise Old Man, the Companions, the Road of Trials, the Trickster, and the Guardian of the Treasure.[3]

Some critics argue that ancient stories filled with magic, monsters and marvels, such as The Odyssey and Beowulf and the tales of the Arabian Nights and the Knights of the Round Table, cannot be called fantasy because the tellers of the tales, and their audience, believed fervently that gods and genies and dragons and magic swords did indeed exist. Yet these are the ancestors of fantasy, just as the tale tellers and their audiences are our ancestors.[4]

Tolkien’s own immediate influences are well known. He loved fairy tales – especially Andrew Lang’s Red Fairy Book – read Lord Dunsany in his youth, and discovered the work of George MacDonald and William Morris while an undergraduate, using the prize money for the Skeat Prize for English to buy a leather-bound copy of Morris’s The House of the Wolfings. Tolkien was well versed in Arthurian legends and Shakespeare (a true fantasist, though Tolkien said he ‘cordially’ disliked him), and he had read T.H. White’s novel Sword in the Stone soon after its publication in 1938. He knew Eric Rücker Eddison, author of The Worm Ouroboros, though he did not like him, and he had been close friends with C.S. Lewis since they had first met in 1926.

Of these writers of the fantastic, William Morris was the first to set his works in an entirely invented world, distinct from ‘long, long ago’ and ‘far, far away’. For many, the creation of such a ‘Secondary World’ – another term coined by Tolkien in his lecture ‘On Fairy Stories’ – is one of the defining characteristics of the genre.

Tolkien would not publish The Lord of the Rings for another 15 years, but by that time the term ‘fantasy’ was being used, if not very widely. The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction began publication in 1949, the year before the first of C.S Lewis’s Narnia books and five years before Volume I of The Lord of the Rings.

When The Fellowship of the Ring was finally published in August 1954, C.S. Lewis wrote on the back cover, ‘It would be almost safe to say that no book like this has ever been written.’

Nowadays, the term ‘fantasy’ seems rather like the mythical hydra – lop off one head and another two spring to life. There’s science fantasy, dark fantasy, adventure fantasy, historical fantasy and romantic fantasy, not to mention new weird, steampunk, magic realism and that useful umbrella term speculative fiction (first used in 1889).

Let me give the last word to George R.R. . Martin, whose latest fantasy novel, A Dance With Dragons, sold 298,000 copies on the first day of its release. He says

The best fantasy is written in the language of dreams. It is alive as dreams are alive, more real than real . . . Fantasy is silver and scarlet, indigo and azure, obsidian veined with gold and lapis lazuli. Reality is plywood and plastic, done up in mud brown and olive drab. Fantasy tastes of habaneros and honey, cinnamon and cloves, rare red meat and wines as sweet as summer. Reality is beans and tofu, and ashes at the end . . .

We read fantasy to find the colors again, I think. To taste strong spices and hear the songs the sirens sang. There is something old and true in fantasy that speaks to something deep within us, to the child who dreamt that one day he would hunt the forests of the night, and feast beneath the hollow hills, and find a love to last forever somewhere south of Oz and north of Shangri-La.

They can keep their heaven. When I die, I’d sooner go to Middle Earth.

[1] Of course, I don’t know if it truly was cold and sleeting on this day, but we are talking about Scotland in early spring. Similarly, I have no idea if the university students were bored-looking and bespectacled, or if any of them were prone to slumbering in lectures, but then again we are talking about university students.

[2] This is according to Tolkien in a letter to Stanley Unwin, his publisher at Allen and Unwin, on 15 October 1937. In the same letter, Tolkien says, ‘If it is true that The Hobbit has come to stay and more will be wanted, I will start the process of thought, and try to get some idea of a theme drawn from this material for treatment in a similar style and for a similar audience – possibly including actual hobbits.’ This process of thought led him, of course, to The Lord of the Rings.

[3] It sounds like a plot outline for The Hobbit, doesn’t it? Just remember that The Hero with a Thousand Faces was published in 1949, 12 years after The Hobbit.

[4] And such a statement also assumes that the readers of modern fantasy do not have their own various beliefs in the mysterious power of magic.