The Blurb (from Goodreads):

The powerful Murrumbidgee River surges through town leaving death and destruction in its wake. It is a stark reminder that while the river can give life, it can just as easily take it away.

Wagadhaany is one of the lucky ones. She survives. But is her life now better than the fate she escaped? Forced to move away from her miyagan, she walks through each day with no trace of dance in her step, her broken heart forever calling her back home to Gundagai.

When she meets Wiradyuri stockman Yindyamarra, Wagadhaany’s heart slowly begins to heal. But still, she dreams of a better life, away from the degradation of being owned. She longs to set out along the river of her ancestors, in search of lost family and country. Can she find the courage to defy the White man’s law? And if she does, will it bring hope ... or heartache?

My Thoughts:

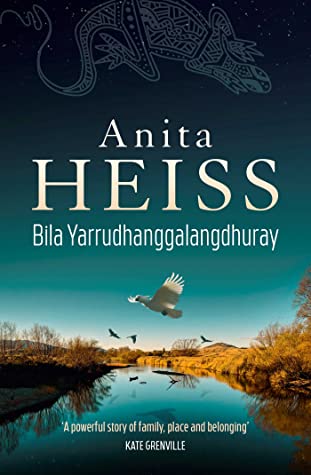

Anita Heiss’s new book is set along the banks of the Murrumbidgee River in the 1850s, and tells the story of a young Aboriginal woman named Waghadhaany (pronounced Wog-a-dine). The title means ‘River of Dreams’ in the Wiradjuri language of southern-central NSW - the river and its landscape and place in the lives of the local Indigenous people are central to this engrossing tale of love and loss, grief and gratitude, language and listening.

The story begins in 1838 when Waghadhaany is only a child, and her father warns a white settler not to build too close to the river, as it floods in the rains and becomes a powerful and dangerous force that sweeps away all in its path. The white man scoffs at him and takes no notice. Wagadhaany askes her father why she does not tell him that the river’s name, Marrambidya, means ‘big flood, big water’. He answers, ‘no matter what you say, or how many times you say it, ngamurr, some people, especially White people, they just won’t listen.’

Fourteen years later, the township of Gundagai was hit by a massive flood as the river broke its banks after a month of heavy rain. Almost one-third of the town’s population died in what was then Australia's worst flood disaster. Many of the survivors were rescued by the local indigenous people, including Wagadhaany’s father. The man he warned, however, dies.

The idea of listening is central to the novel. Wagadhaany must learn the language of her white employers, but they do not learn hers. They call her Wilma because they cannot be bothered to learn how to pronounce her name. Much of the wisdom of the Wiradjuri people is transmitted orally, through song and story. Yet Wagadhaany is taken away from her people and her country, and this loss wounds her. She is kept silent.

In one scene, she visits another camp and realises: ‘she’s had no conversation since leaving Gundagai. No language, no stories, no dancing, no sharing. She wonders how she can still live without so much that is important to her. She looks around the circle where the women are weaving and knows they must all be listening, because no-one else is talking.’ To find herself once more among her own kind hits Wagadhaany hard: ‘These women could be her gunhi, her grandmother, aunties and cousins. These could be her miyagan. She remembers the words of her own gunhi the last time she saw her. You will always have miyagan around this country, your Wiradjuri country … the Ancestors will be with you wherever you walk.’

The simplicity and naivety of the language is a perfect expression of Wagadhaany’s voice. Although she uses many Wiradjuri words, their meaning is always clear in the context of the story, and Anita provides a glossary at the back of the book just in case. I really loved this use of the Wiradjuri language throughout the story – it's a paean to an ancient culture steeped in myth and song and storytelling.

The loss of language, the loss of country, is the force which drives Wagadhaany as she grows up, makes friends, falls in love, and becomes a mother. Eventually, this force compels her to break free of her servitude to her white employers and she walks home, following the snaking course of the river of dreams. The novel flows like the great Murrumbidgee River itself, with powerful undercurrents that sweep the reader along.

The book is written with great delicacy and compassion. Wagadhaany grows from a girl filled with bewilderment and grief at the disruption of her world to a young woman of certainty and strength. And not all the white settlers are callous and unjust. Wagadhaany makes friends with a young Quaker woman named Louisa who tries to listen and understand, though her attempts to help are sometimes tone-deaf. It's so incredible to hear the story of Australia's colonial past in the voice of an Indigenous woman. It really illuminated our past for me, and taught me so much about a way of life that has sadly been largely lost. I feel Bila Yarrudhanggalangdhuray is a book that all Australians should read, to try and understand why our colonial past still causes so much pain and grievance.

You might also like to read my review of Barbed Wire & Cherry Blossoms by Anita Heiss: