The Blurb (from Goodreads):

Berlin, 1938. The eve of war. Ernst Schäfer, a young, ambitious zoologist, keen hunter and devoted husband of the beautiful Herta, has come to the attention of Heinrich Himmler, who invites him to lead a group of SS scientists to the frozen mountains of Tibet. Their secret mission: to search for the origins of the Aryan race. For Schäfer, the personal consequences of failure are unthinkable, yet little does he know this outlandish expedition will become a prelude to the unimaginable horror soon to overrun Europe.

Using material discovered in field diaries, letters, films, photographs and secret documents, the novel tells the story behind Schäfer through the eyes of his ill-fated lover, Herta. Nazism proved a convenient short-cut to personal glory for Schäfer, who, accompanied by a group of SS scientists, trekked across inhospitable, treacherous terrain on a mission to conduct experiments to 'prove' Nordic heritage. In 1939, the team was flown out of India on Himmler’s flying boats. Schäfer was an instant celebrity on his return to Berlin and, at just twenty-eight, he became one of the most celebrated men in Hitler’s Reich. But his world was about to change, as science was enlisted for racial murder and Himmler sent Schäfer to Dachau to observe and film medical experiments.

The Hollow Bones explores how quickly human relationships and an affinity with nature can be buried under cold ambition.

My Thoughts:

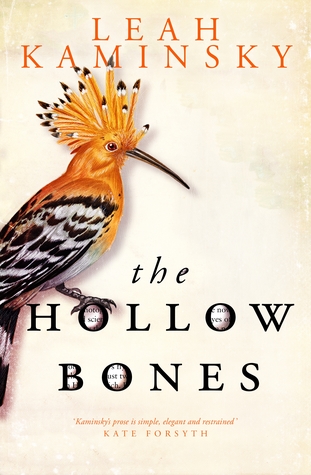

Books set during World War II are immensely popular at the moment, and I read a great many of them because it is one of my favourite periods in history. The Hollow Bones by Leah Kaminsky is one of the most unusual I’ve read. Inspired by the true story of the 1938 expedition to Tibet by the German zoologist Ernst Schäfer, it is not a conventional historical adventure story but a slow, melancholy magic realist novel that reflects on the nature of complicity and the very purpose of life.

Ernst Schäfer’s expedition to Tibet was funded by Heinrich Himmler, head of the sinister Schutzstaffel (SS), who wished to find proof that the Germans were descended from an ancient warrior race. Schäfer does not care who funds his research, as long as he gets to pursue his passion for hunting and collecting. His loving wife Herta is not so sure. She has a disabled sister who is kept hidden for fear the authorities will think their bloodline is tainted; no SS officer could marry unless his wife could prove the purity of their blood.

The novel moves back and forth between the points of view of Herta and Ernst, with a series of poignant scenes that show the difficulty of remaining morally uncorrupted in a world ruled by Nazis. Then another narrative thread emerges, one that is most unexpected and unique: the voice of a baby panda which was shot and stuffed by Ernst Schäfer and is kept in the Philadelphia Museum of National History. The baby panda tells his story in short, stilted sentences that are sometimes childish and sometimes profound:

‘I trouble them; my Death makes them feel uncomfortable. But how is my Eternal Life any worse than Crocodile whose skin covers President’s feet, or Cow whose hide is worn by Small around her middle? I command more respect than the Animal Parts they wear, carry, eat; at least my life has not been anonymously erased.’

At first, I was not sure of the intrusion of the voice of this sentient stuffed animal, particularly when the cub refers to seeing the Writer (i.e. Leah Kaminsky herself) visiting the museum:

‘Writer came once and visited me every day for an entire week they called Fellowship … Writer reads to me sometimes and apologises, calling herself a voyeur. Her heart is heavy because I was torn away and preserved, but her hand pushes Magic Stick furiously across the blank page because I am here. She tells me I am the true Storyteller … My Visitors are like her Readers, she says, each one claiming ownership over the interpretation of the story I tell.’

This authorial intrusion into a work of fiction took me aback. At first I did not like the self-conscious tone, the awkwardness of the device. ‘What a fickle, grumpy woman Writer can be,’ the panda says. But I admired Leah Kaminsky’s boldness in making such an unusual narrative choice, and in the end it became one of my favourite parts of the novel. It gave the book such moral gravity and such freshness of tone. And I’ve continued thinking about the book long after I turned the last page.

If you've enjoyed this review, you may like Citadel by Kate Mosse:

https://kateforsyth.com.au/what-katie-read/vintage-book-review-citadel-by-kate-mosse