If there is any joy in this world greater than discovering a new book to love, it is rediscovering one that you have loved and lost.

I willingly confess to being a bibliomaniac. This is, according to Maurice Dunbar, ‘a victim of the obsessive-compulsive neurosis characterized by a congested library and an atrophied bank account.’ Our house is inhabited by books, old ones, new ones, those still waiting to be read, ones that have been re-read a hundred times. There are books on every imaginable subject, for I like to be able to put out my hand and find the answer to whatever question is haunting my curiosity. Most of my books, though, are fiction. ‘Fiction is king,’ as Francis Spufford wrote so cajolingly in ‘The Child that Books Built’; (another book I love). ‘Fiction is the true stuff, compared to which non-fiction is just a shadow.’

‘We hope,’ he wrote, ‘(that fiction) can bring a fully uttered clarity to the living we do, which is, we know, so hard to disentangle and articulate. And when it does, when a fiction does trip a profound recognition … the reward is more than an inert item of knowledge. The book becomes part of the history of our self-understanding. The stories that mean most to us join the process by which we come to be securely our own.’

It is Spufford’s argument that the books we read over our lives, but most particularly the books we read as children, that make us who we are. All of us who are ardent readers will be able to name those books which had the most profound effects upon us at different times of our lives. My memory of my childhood is vague and fragmentary at best, yet I can remember every book I ever read and usually where I was when I read it. As I like to own books, this means I will often hunt for years to find a book that I’ve read and loved and lost. Since many of the books I read as a child are now out of print, this means I love jumble sales, church fetes, and second-hand bookshops. I love all bookshops, but the old ones have a special allure about them, the hope of stumbling across Aladdin’s cave in a box of shabby old paperbacks.

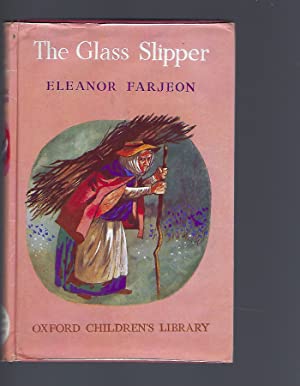

Just yesterday I found a book I have been searching for since I was seven years old. That’s thirty-two years of looking. The book was ‘The Glass Slipper’ by Eleanor Farjeon. I borrowed it from my school library and was utterly enchanted by it. I remember I began reading it on my way home from school (I often used to read while walking home from school, and today, whenever I see a child doing the same, I always smile with a real sense of warmth and comradeship). I became so engrossed in ‘The Glass Slipper’ that I walked straight past the end of my street, and only came to myself four blocks further on, when my sister’s best friend’s mum honked me as she drove past, laughing.

I turned myself about and read all the way home. I finished the book on the way down the stairs to the dinner-table that night, and was as replete and satisfied as any glutton after a king’s feast. I borrowed the book again several times, and when I left my primary school for high school, it was one of the things I most regretted having to leave.

Perhaps the best way for me to describe the shaping power this book had on my imagination is to confess I named my daughter Eleanor, and that we call her Ella for short, a name for which I’ve had a soft spot ever since reading this classic retelling of the Cinderella tale. It would be untrue to say that Eleanor Farjeon and her sweet-faced heroine Ella were the only influences on my choice of name. Ellen is a family name, and I’ve always liked Queen Eleanor of Aquitaine, and often thought I would like a tombstone like hers – she lies sculpted in stone on the lid of her tomb in the Abbey of Fontevrault, holding open a book. It would be true to say that Eleanor Farjeon and this book were strong influences, however, which goes to show just what a profound recognition it tripped in me at the age of eight.

‘The Glass Slipper’ is one of the books that began my lifelong fascination with fairytale retellings, and with tales of magic and marvel, one which drives my writing today. It is told simply, but with such wit and humour, charm and playfulness, that it is far fresher than any other version of the old tale I’ve read. Yet it is not a book that can be bought in any good bookstore – it has been out of print as long as I’ve been alive. Most people have never even heard of Eleanor Farjeon, yet she wrote more than thirty works of fiction, three plays, thirty-three collections of poetry, and numerous biographies and memoirs. There is an award for children’s literature named after her in the UK, and she wrote the words to the hymn ‘Morning has Broken’, which Cat Stevens turned into a mega-hit in the early ‘70s.

Born in 1881, the daughter of a novelist and granddaughter of an actor, Eleanor Farjeon was brought up in a household of books, and encouraged to write from an early age. At the age of eighteen, she wrote the lyrics to an operetta penned by her brother Harry which was performed at St George’s Hall in London. At nineteen, she sold her first story for three guineas, a fairytale called ‘The Cardboard Angel’ She counted D.H. Lawrence, Walter de la Mare and Robert Frost among her friends, and received the Hans Christian Anderson Medal in 1956.

‘The Glass Slipper’ was first written with her brother Herbert as a play in 1944, and turned into a book in 1955. Eleanor’s love of poetry and song comes through in every line – it has the sort of playfulness with language that is rarely seen nowadays.

‘When (Ella) was refused (permission to go to the ball), she clung to the last few minutes of the spilt finery, the hasty scramble out of the house, the little squeaks and shrieks on the slippery path: ‘It’s freezing! It’s freezing! Go carefully! Hang on to me! stop gripping me! you’re tripping me! Oops! Ma was nearly down that time! I’m petrified! I’m paralysed! Stop dragging me! stop nagging me! I’m dithery! It’s slithery! OOOPS! Ma was really down that time! We’ll be late, we’ll be late! Look alive, look alive! The horses are waiting at the end of the drive …’

Eleanor Farjeon once wrote of herself, ‘I can hardly remember a time when it did not seem easier to write in running rhymes than in plodding prose,’ and this facility with rhythm and rhyme can be heard on every line.

It is, of course, a strange and poignant experience, reading again as an adult a book one had loved as a child. The scales of innocence are lost from our eyes; we have inherited a world-weariness along with our wisdom. I always loved Enid Blyton when I was seven, but reading her now to my seven-year-old son, I cannot help grinning when one of her bossy boys says ‘I came over all queer.’ I find myself subtly editing as I read, even though I strongly disapprove of trying to modernize old stories, much of whose charm comes from the stiltedness and strangeness of the language.

Reading ‘The Glass Slipper’ again, I was conscious of the distance between myself as a child, discovering the tale for the first time and being utterly enchanted, and me as an adult wishing Ella would be a little less sweet to her nasty step-sisters. Yet now that I have it in my hand again, I cannot wait to read to my own children, and particularly to my own Ella, the story of Cinderella, “barefoot, tangle-haired and tattered, but with a face as fresh as a flower.’