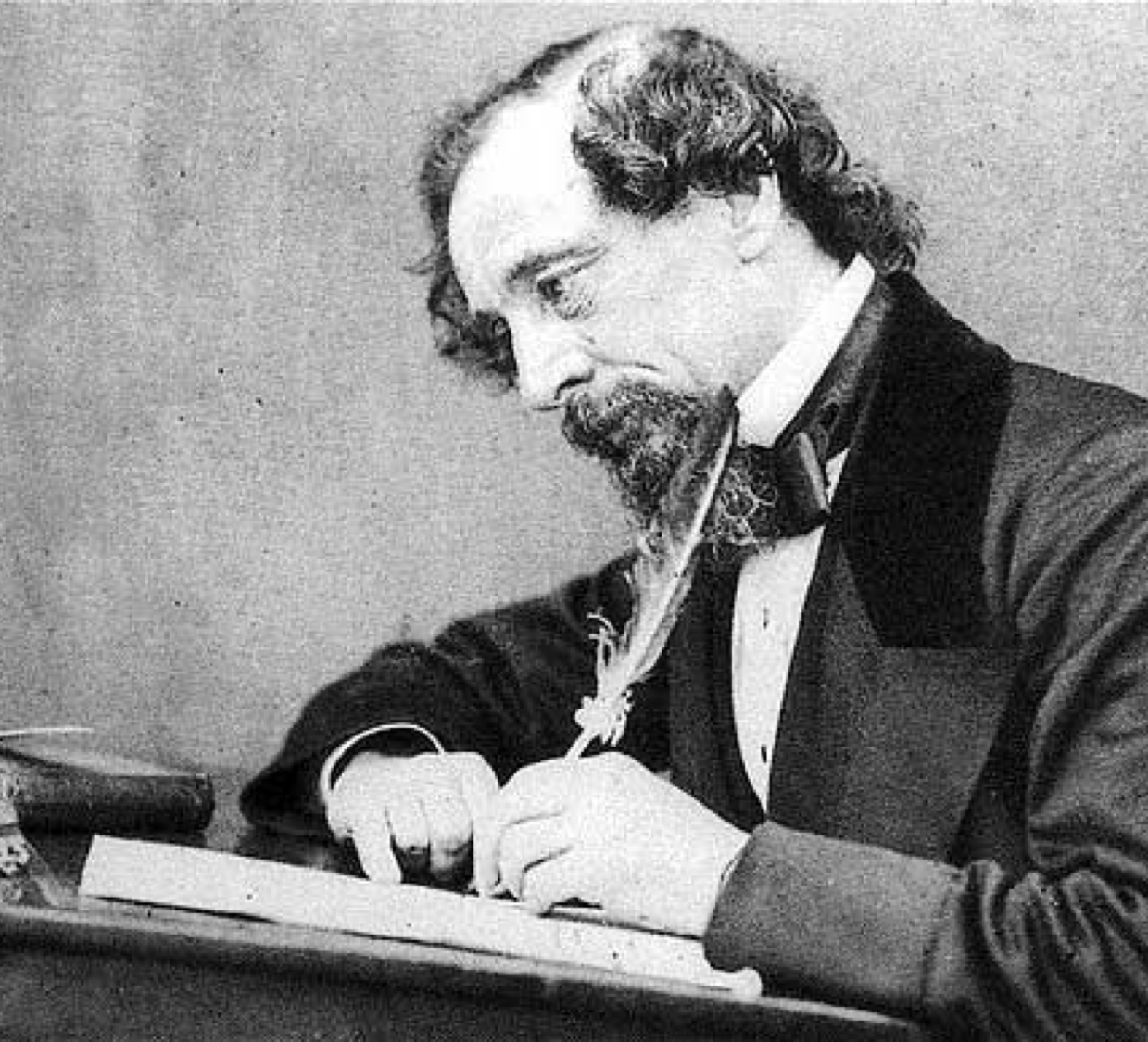

A Tale of Two Cities was Charles Dickens’s twelfth novel, and was written and published at a tumultuous time of his life. He was at that time in his mid-40s, unhappily married with ten children aged between 20 and 5.

He was already famous, having written such great classics as Oliver Twist, Nicholas Nickleby, David Copperfield and Bleak House. His most recent novel, Little Dorrit, had won him more readers than ever.

Dickens had also been busy working on ‘The Frozen Deep’, a play written and staged in collaboration with his friend Wilkie Collins. The story was inspired by the true story of a doomed expedition to the Arctic in 1845, led by Sir John Franklin, former Lieutenant-Governor of Van Dieman’s Land. The explorers hoped to chart the Northwest Passage, but the expedition was lost without trace.

‘The Frozen Deep’ begins when a young woman named Clara Burnham becomes engaged to Frank Aldersley the night before he joins an expedition to find the Northwest Passage. Clara is an orphan, staying with her best friend, Lucy Crayford, whose husband is a lieutenant on the voyage. The same evening Clara rejects the advances of another man Richard Wardour. Vowing revenge on his rival, Wardour joins the expedition at the last minute.

Two years later, their ships are trapped in the Arctic ice with most of the expedition dying from cold and starvation. When the two men become separated from the main group, Wardour is tempted to leave his rival to die. Lucy and Clara have sailed to Canada to seek their lost lovers. Wardour staggers from the snow, carrying Aldersley in his arms – he has saved his life at the cost of his own.

The play was first performed as an amateur theatrical at Dickens’ home, Tavistock House, on 5 January 1857, for an informal audience of servants and tradespeople. Dickens acted the role of Richard Wardour and was the play’s stage-manager. Several other performances followed, to audiences of the two authors’ friends and colleagues.

Then a close friend of Dickens – Douglas William Jerrold – unexpectedly died, and Dickens decided to stage some benefit performances of the play to help raise funds for his widow and children. The first was a command performance on 4 July 1857 for Queen Victoria, Prince Albert, and their family and guests, who included William Thackeray and Hans Christian Andersen. Queen Victoria praised the performance, especially Dickens's acting, in her diary.

Realising that insufficient funds had been raised to sustain Mrs. Jerrold and her children, Dickens arranged for a series of much larger public performances at the Manchester Free Trade Hall. He was concerned that his amateur actresses, including his daughters Kate and Mary, would not be able to project their voices in such a large venue. So he hired professional actresses, including Fanny Ternan and her daughters, Maria and Ellen (called Nelly) who was then just 18 years old.

Their three performances, given on 21, 22 and 24 August 1867, were attended by thousands, many of whom were moved to tears by the play – including the stage crew and cast.

A week later, he wrote to his friend John Forster that his relationship with his wife was breaking apart: ‘Poor Catherine and I are not made for each other … reasons have been growing which make it all but hopeless that we should even try to struggle on.’ Within the next few weeks, Dickens had moved out of the marital bed and into a separate bedroom.

Around the same time, he wrote to Angela Burdett Coutts about a new idea growing in his imagination: ‘Sometimes of late, when I have been very much excited by the crying of two thousand people over the grave of Richard Wardour, new ideas for a story have come into my head as I lay on the ground, with surprising force and brilliancy. Last night, being quiet here, I noted them down in a little book I keep.’ This was the first mention of the story idea that would become A Tale of Two Cities.

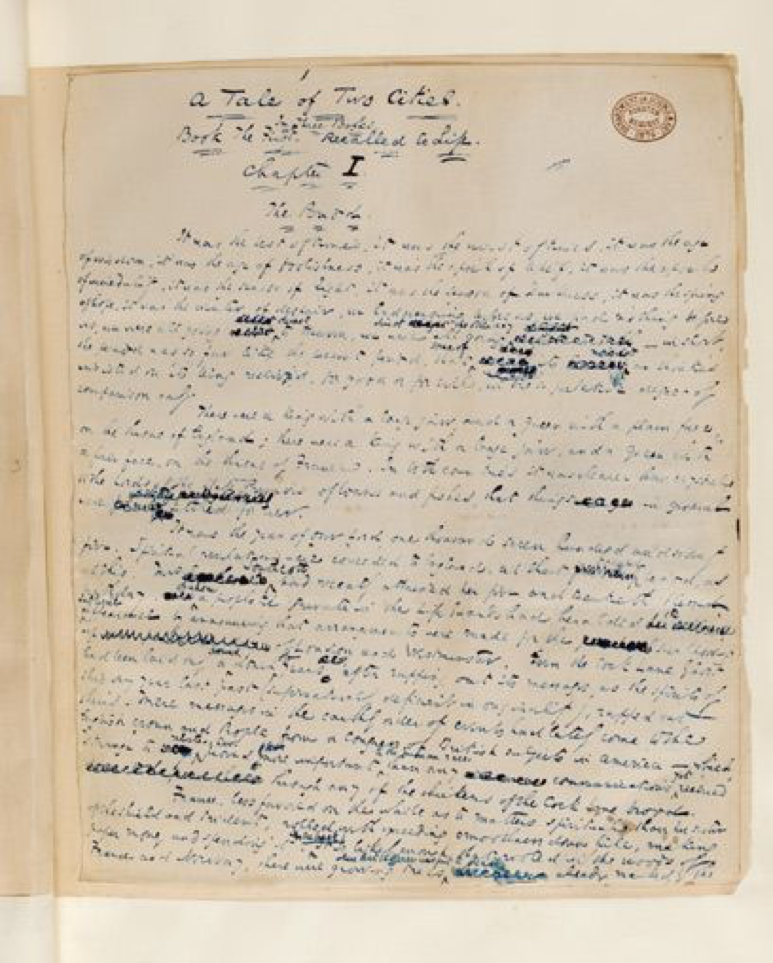

His notebook from the time read: ‘a story in two periods – with a lapse of time between, like a French drama.’ And, a little later, ‘The drunken? – dissipated? – What? LION – and his JACKAL …’

In late January 1858, he wrote to John Foster that he had enough ideas for a book ‘if (only) I can discipline my thoughts into the channel of a story.’ In March, he sent Forster three possible titles, including ‘Buried Alive.’

In May, Catherine Dickens accidentally received a bracelet meant for Ellen Ternan. Her daughter, Katey, said her mother was distraught at the discovery. By the end of the month Dickens had negotiated a settlement where Catherine should have £400 a year and a carriage, but the children would live with him. His eldest son Charley was over 21 and so permitted to choose where he lived. He decided to stay with his mother.

There were inevitably, rumours and scandal. In June 1858, Dickens issued a statement to the press: ‘By some means, arising out of wickedness, or out of folly, or out of inconceivable wild chance, or out of all three, this trouble has been the occasion of misrepresentations, mostly grossly false, most monstrous, and most cruel - involving, not only me, but innocent persons dear to my heart... I most solemnly declare, then - and this I do both in my own name and in my wife's name - that all the lately whispered rumours touching the trouble, at which I have glanced, are abominably false. And whosoever repeats one of them after this denial, will lie as wilfully and as foully as it is possible for any false witness to lie, before heaven and earth.’

Kate Dickens later recalled: "My father was like a madman... This affair brought out all that was worst - all that was weakest in him. He did not care a damn what happened to any of us. Nothing could surpass the misery and unhappiness of our home."

Dickens could not write. Almost a year later – in February 1859 - he said, ‘I cannot please myself with the opening of my new story, and cannot in the least settle to it or take to it.’

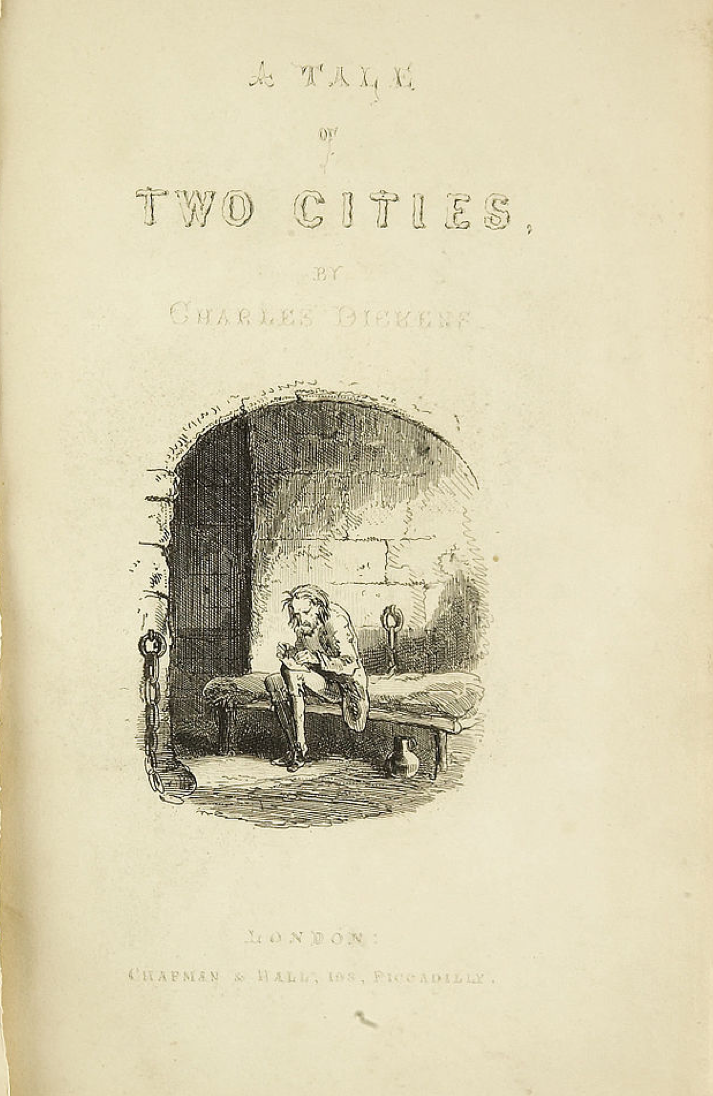

However, only a few weeks later the title came to him - ‘exactly the name for the story that is wanted’ - and he ordered Thomas Carlyle’s history of the French Revolution from the London Library. ‘All the time I was at work on the Two Cities, I read no books but such as had the air of the time in them.’

By 5th April he was writing steadily, and the first installment was published on the 30th of that month. Dickens then had to produce exactly eight columns of text a week, for the weekly serialisation, with the last chapter printed only six months later, in November. He felt cramped and rushed by these constant deadlines, writing: ‘The difficulty of the space is crushing. Nobody can have an idea of it who has not had an experience of patient fiction-writing with some elbow-room …’

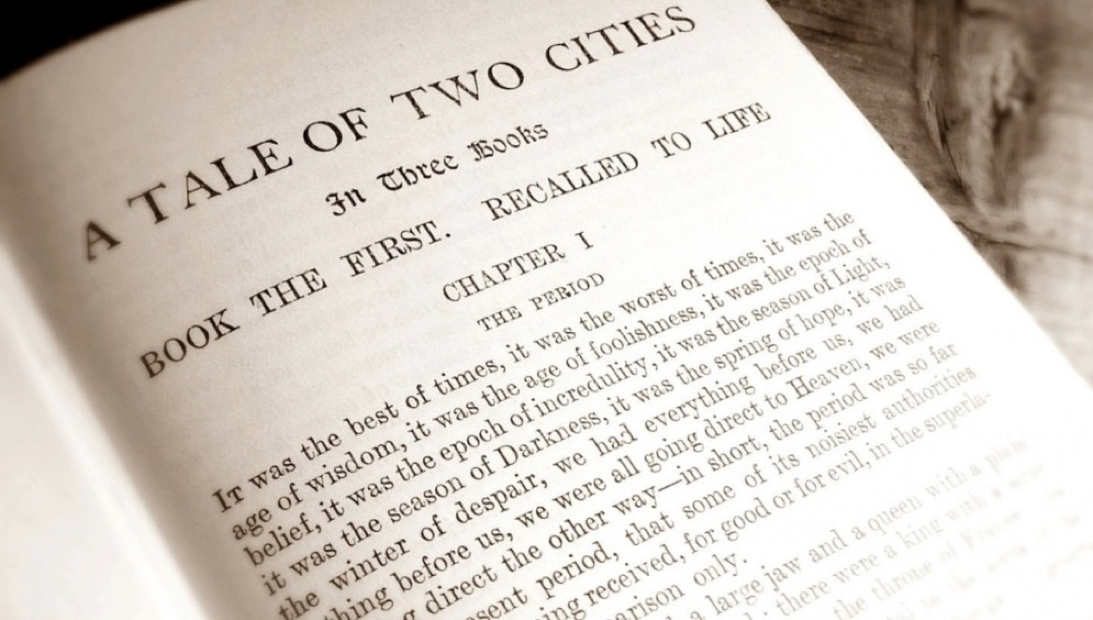

A Tale of Two Cities has been criticised for its swiftness of pace, its tight compression of time, and its simplicity of plot, but I actually feel this distillation down to the quintessence is why the story is so powerful.

The characters are drawn simply but deftly, without exaggeration or caricature, and yet they are entirely memorable: the old man kept prisoner for 18 years, making shoes from scraps of leather; gentle Lucie who shows such courage and strength of character in her steadfast support of her broken father; Charles Darnay, her lover who hides a secret past, and his doppelgänger, the debauched young lawyer Sydney Carton who finds redemption in love and self-sacrifice; and – perhaps most vitally - sinister Madame Defarge, whose knitting secretly encodes the names of those whom she wants to die;

The pace is swift and compelling, the plot is full of mysteries and surprises, and each scene is so vivid and memorable – the child knocked down and killed by an aristocrat’s carriage; the murder of the evil marquis; the storming of the Bastille; the death carts with their doomed human cargo, rattling over the cobblestones; the terrible swift drop of the guillotine blade ….

All this occurs against the background of the French Revolution, a time of terror and treason, in which the world is changed forever. The sheer drama and tragedy of its historical setting, and the book’s powerful themes of revolution, redemption and resurrection, combine to make – I believe - ‘A Tale of Two Cities’ Dickens’s greatest novel.

Dickens himself agreed with me, writing to a friend on the 15th of October, 1859: ‘I hope it is the best story I have written.’

10 Fascinating Facts About A Tale of Two Cities:

Charles Darnay shares the same first name and initials as Dickens himself

Evrémonde - his French surname – means ‘everyman’

The book’s Lucie shares the same name as the character played by Ellen Ternan in the Frozen Deep.

Lucie’s father was driven mad by his 18 years in prison; Ellen’s father died in the Bethnal Green Insane Asylum.

Dickens referred to Ellen Ternan as his ‘magic circle of one’; Sydney Carton said to Lucie: ‘I wish you to know that you have been the last dream of my soul.’

Dickens once witnessed a beheading by guillotine in Rome in 1845

Dickens said he read Thomas Carlyle’s The French Revolution 500 times while writing A Tale of Two Cities

Real-life characters in the book include Charles-Henri Samson, the Royal Executioner of France, who executed around 3,000 people during the Terror, including the French king

The second part of the book is ‘The Golden Thread’ gave its name to a famous English Legal Judgement: ‘one golden thread is always to be seen – that is the duty of the prosecution to prove the prisoner’s guilt’ ie the Common Law concept of the presumption of innocence common in the English speaking world.

Charles Dicken’s favourite fairy tale character was Little Red Riding Hood, a traditional French story full of darkness, sexual tension, and a man who saves a girl by cutting her from the belly of a wolf after it had devoured her.