I have been watching & listening to the anger & anguish of the #BLM movement these past few weeks, with tears burning my eyes and a great choke of grief in my throat. As an Australian, I am particularly moved by the #AboriginalLivesMatter. I find our long and ugly history of racism, injustice and cruelty unbearable and unendurable, and I have always tried, in my own small way, to express my shame and sorrow.

This past weekend, I was shown – very gently and respectfully – that I was not doing enough. I was contributing to the great white silence by not speaking up, by not adding my voice to the thousands shouting themselves hoarse. The small things I try to do are really not enough.

I’ve been thinking & worrying & thinking & worrying about it all week, and I’ve decided that I must do more. But what can I do? I’ve asked myself again and again. Reading and retweeting and liking and sharing is easy. I need to do something that is difficult, that costs me in some way, that is a long-term change in the way I deal with this great and terrible issue of our times.

I believe passionately that storytelling has true power to change the world, because stories have such a way of piercing the heart. I have always tried to affect change in the world by the stories I tell. I say, ‘we all have the right to tell our stories, we all have the right to lift up our voices.’

All I really know is storytelling.

And so I thought I would set up a kind of fellowship to help Indigenous writers find their voices and tell their stories. What I want to give is my time, my knowledge, my insight – something that will cost me dear as my own writing time is so precious to me and so hard to guard. I was thinking that, every year, for as long as I am wanted, I will give an hour a month to one Australian Aboriginal creative artist, just to listen and talk and give advice and read their work and give feedback, if wanted. One hour every month for the twelve months of the year. Every year.

I’m thinking of calling it the Errombee Fellowship.

To explain why, I need to tell you a story about my family.

My great-great-great-great-grandfather James Atkinson emigrated to Australia from England in late 1819, arriving in Port Jackson in May 1820. He worked for two years for Governor Lachlan Macquarie as principal clerk in the Colonial Secretary’s office and was given 1,500 acres of land at Sutton Forest in the Southern Highlands of NSW (in our family myth, he was told he could have as much land as he could ride around in a day). He established a farm there in 1821, naming it Oldbury after his birthplace in Kent.

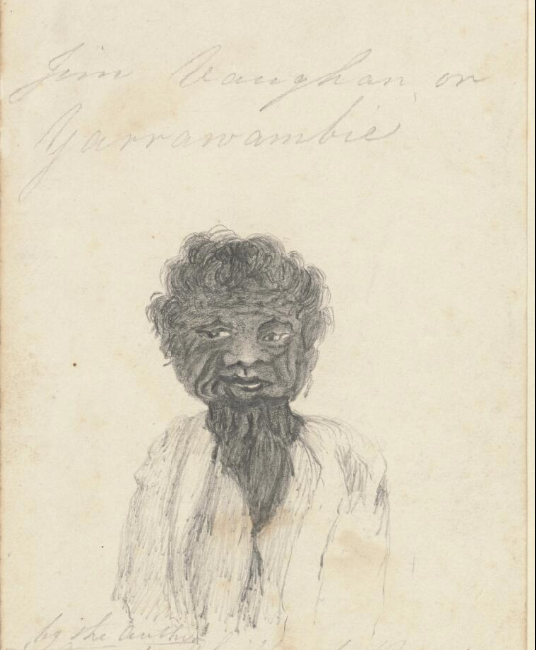

The beautiful rolling landscape he claimed lay to the south of Gingenbullen Mountain and belonged to the Wodi Wodi people of the Dharawal Nation. Their leader was a man named Errombee (sometimes called Yarrawambie or Jim Vaughan). James described him as ‘an elderly man of the most quiet inoffensive disposition’ and his ‘tribe … the most docile and peacable possible.’

In 1822, James set out to explore the countryside between Sutton Forest and the coast, looking for grazing land and red cedar. Errombee was his guide. They became lost in the deep forest gorges of the Shoalhaven. When their provisions ran out, Errombee caught and roasted a goanna and harvested honeycomb for them to eat, but gave all the food to James.

Errombee saved my great-great-great-great-grandfather’s life, and so enabled me to be born.

What an extraordinary act of kindness, generosity and forgiveness!

So it seems fitting to acknowledge him in this small way, and to try and give something back for the gift of life he gave.

I need to think about the best way to set up this fellowship, and establishing a few guidelines to how it might run, and so any feedback or advice you can give me would be most gratefully received!

PS: this pencil drawing of Errombie was made by my great-great-great-great-aunt Louise Atkinson in 1863, to illustrate an article about the lives of Australian Aborigines which was published in the Sydney Mail. In that article, Louisa called the English colonials ‘white invaders’, the first person to do so. It is held at the National Library of Australia.