When my sister Belinda and I wrote Searching for Charlotte: The Fascinating Story of Australia’s First Children’s Author, we originally planned a chapter in which we explored Charlotte Waring’s family ancestry. However, by the time we had written the book, it was too long (a very common problem!)

So I reluctantly cut out the chapter I had written about the Waring family. The research had taken me months to do, and I had loved writing it. But of all the chapters in the book, it was the least important. We wove a little of it into one of Belinda’s chapters (if you’ve read the book, you’ll recognise which bit, I’m sure.)

However, I thought I’d share the lost chapter with you, just in case you’re interested. It’s all about William the Conqueror and the Battle of Hastings and the Bayeux tapestry, so as you can see it really does not have much to do with my ancestor Charlotte’s journey to write Australia’s first children’s book. Nonetheless, I hope you find it interesting. Happy reading!

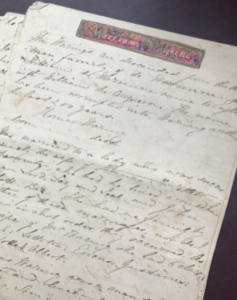

Buried deep in the archives at the Mitchell Library, the oldest library in Australia, is a folder containing a sheaf of loose pages, inscribed in elegant nineteenth-century calligraphy. They were written in 1872 by my great-great-great-great-aunt, Louisa Atkinson, the first Australian-born female novelist, for a baby daughter she would never see grow up.

The first page is headed by the words ‘Warrenne Waring’, beautifully drawn and coloured, for Louisa Atkinson was an artist as well as an author.

Outside, the rain beats down on the pavement and umbrellas jostle for space. Inside, the sacred hush is occasionally disturbed by a murmur of voices or the rustle of paper. It’s Wednesday, 21st September, and my sister Binny and I have come together to read these old, fragile, difficult-to-decipher pages as our very first act of research together. We know that they contain a brief history of our family.

The opening lines read: ‘The Warings are descended from the Norman family of de Warrenne. William de Warrenne came to England with William the Conqueror. The name has been corrupted into Waring within the last two hundred years.’

The first page of Louisa Atkinson’s handwritten family memoir

Image source: The Mitchell Library

This is not a new discovery for us. When we were children, our grandmother had often told us that Charlotte Waring’s ancestors came from France to fight at the Battle of Hastings.

Even though William the Conqueror invaded England in 1066, nine hundred years before I was born, I was always proud of my drop of French blood. I imagined it gave me a certain flair for clothes. I read biographies of Colette and Anaïs Nin and Coco Chanel, and visualised myself sitting at a cafe on the Left Bank, wearing a velvet beret and drinking absinthe as I wrote ecstatic poetry.

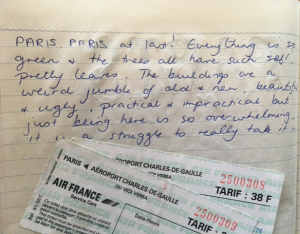

When I was in my mid-twenties, I travelled overseas for the first time. I went with the man who would one day be my husband. We flew straight to Paris, the place I had most longed to see. On arrival, I wrote in my diary: ‘PARIS. PARIS at last!”

A page from Kate’s diary, 10th September 1991

I have been to France many times since then.

In the summer of 2016 – nine hundred and fifty years after William the Conqueror and his knights set sail from Normandy - I travel to Bayeux with my friend Susie to see the famous tapestry. In French, it is known both more poetically and more precisely as La Broderie de Bayeux, for it is an artwork embroidered by hand in seven different coloured threads on a very long strip of linen.

Bayeux is one of those rare places in the world where time seems woven of the most fragile of fabrics. It was the first town to be liberated by Allied forces on 7th June 1944 - the morning after D-Day – and so it escaped much of the bombing other Norman towns suffered. Half-timbered houses lean over narrow cobblestone streets, and an old mill-wheel churns the water flowing under an arched stone bridge. The tall pointed spires of the cathedral soar into the twilight-blue sky. Inside the nave, a young girl in a long white dress curtsies to the altar and crosses herself. The last of the sunlight shafts through intricate stained glass upon the marble floor, worn into hollows where generation upon generation have knelt and prayed.

As we wander through the old town in the warm dusk, iron lanterns kindling above ancient wooden doors, it is easy to imagine knights in heavy armour clopping through the square upon their destriers, young women in gowns with dangling sleeves throwing flowers.

Susie and I are the first in the queue at the Bayeux Tapestry Museum the following morning. Slowly we pass through the long curving tunnel where the embroidery is housed behind protective glass. It has been described as the world’s first cartoon strip: it is more than 70 metres long but only 50 centimetres high, and the story unfolds as a sequence of vividly rendered scenes, like the storyboard for a film.

As I examine each tiny stitch, I wonder if any of these men seen fighting, burning and killing was William de Warenne, or if that brown splotch was a bloodstain from the pricked finger of his wife-to-be Gundred, one of the queen’s ladies-in-waiting rumoured to be an illegitimate daughter of the Conqueror. I wonder how they met, and if they loved each other, and if they were happy.

I tell Susie that my family is descended from one of these Norman knights, then laugh. I say, ‘Maybe it’s not true. Maybe it’s just a story.’

I don’t want to seem as if I’m boasting. Everyone is descended from someone. It’s just that my family is lucky enough to have literate forebears whose lives were documented in the historical record. Very few people can say the same. In England in the 16th century, 500 years after the Norman invasion, 90% of men and 99% of women could not read or write. This seems so sad. Their lives were – as engraved on the poet John Keats’s grave in Rome – ‘writ in water’.

The story of my ancestors begins in the 9th century when a fleet of Vikings sailed up the Seine to Paris, which was just a small walled village on a little island in the middle of the river.

Paris had been looted numerous times before, and so had built fortified bridges across the river to block the longboats. The Vikings were repulsed, but settled in for a long siege.

After almost a year, the king of France came to help. He drove off the invaders but then offered one of the leading jarls all the land between the mouth of the Seine and Rouen in return for protection against further Viking raids. The warrior who won all this rich and fertile land was named Hrólf the Walker, because he was so huge no horse was strong enough to carry him. He became Count Rollo of Normandy, his lands named from the Old Norse word Norðmaðr or ‘northman’.

Rollo consolidated his power by marrying into the highest level of French nobility. His son was William Longsword, and his grandson was Richard I, known as the Fearless.

One day Richard went hunting in the forest, and stayed the night at the house of one of his foresters. The forester, it was said, had a most beautiful wife named Sainfrida. As soon as Richard saw Sainfrida, he wanted her. He asked her to come to his bed that night.

Sainfrida had no wish to be seduced by the duke, but did not like to displease him. So she decided to trick the duke by sending one of her unmarried sisters to his bed in her place. Her youngest sister Gunnora agreed to the substitution, and made her way in the darkness of the night to Richard’s room.

The duke was so delighted with Gunnora that he forgave Sainfrida for her trick, and thanked her for saving him from the sin of adultery. He married the forester’s daughter, and they had three sons and three daughters together. Her other sisters and brother married into Norman nobility, and in time their descendants (which included my ancestor William de Warenne) formed a powerful and loyal following for the dukes of Normandy.

Gunnora’s eldest son inherited the dukedom on his father’s death in 996, and became known as Richard the Good. His sister Emma was married to the English king, Ethelred the Unready. After Ethelred died, Emma was forced into marriage with Canute, who had invaded England and won its throne in 1016. He is most famous for proving that no king, no matter how powerful, could turn back the tide. Emma’s marriage is significant because she was the only woman in history to marry two kings of England; and because later it gave her grand-nephew, William the Conqueror, a claim to the throne of England.

Richard the Good died in August 1026, and the duchy of Normandy was inherited by his eldest son, also called Richard, who was then in his 20s. His younger brother Robert was discontented with his inheritance and rebelled, laying siege to the castle of Falaise.

One day, he noticed a beautiful young woman washing her linen in the castle moat. She was a peasant girl, and her father was a tanner of hides. She noticed the young nobleman staring at her, and hitched up her skirts so he could see her shapely legs. Robert was immediately smitten and ordered her brought to him through the back door.

The young woman – whose name was Herleva – refused.

‘I will only enter the duke’s castle on horseback through the front gate,’ she declared. Robert eventually agreed, and Herleva rode proudly through the castle gate on a white horse.

That night, she dreamed a tree sprang from her womb. It grew so tall and strong its shadow darkened all of Normandy, then stretched across the sea to eclipse the kingdom of England. A few weeks later, Herleva discovered she was pregnant.

Soon after, her lover Robert was captured by his brother, the duke. After Robert swore an oath of fealty, the duke rode back to Rouen where he died suddenly and suspiciously. He had ruled for less than a year.

Robert promptly declared himself the next duke. Herleva’s son was born soon after. He was known as Guillaume le Bâtard, or – in Anglicised form – William the Bastard. Six years later, his father the duke decided to go on pilgrimage to Jerusalem. Some suggest that Robert was haunted by guilt over the murder of his brother, others that he sought absolution for his many affairs with women. Whatever the reason, he never returned. He died in what is now Turkey in July 1035.

His son William was only eight years old.

It is at this point in the long and bloody history of Normandy that the de Warennes first enter the written record.

Sometime between 1037 and 1055, a man named Rodulfo Warethnæ agreed to sell land to the Abbey of the Holy Trinity, which lay outside the city wall of Rouen. Another charter named his wife as Beatrice. She is believed to be Beatrice de Vascoeuil, the grand-daughter of Duchess Gunnora’s sister, Avelina. This means that she was Duke Robert’s second cousin.

In 1059, a man named Rodulfus de Warenna sold another four parcels of land to the same abbey, with his wife Emma as his witness. For a long time, it was thought that Rudolfo/Rodulfus were the same man with two different wives. However, recent research indicate the charters refer instead to a father and his son.

The situation is complicated by the lack of standard spelling. Records of the time sometimes spell the same name in different ways in the same document. Rodulfus appears as Ralph, Ranulph, Ranulf, Rodolph or Rudolph, the name most modern-day historians use. Similarly, my ancestors’ last name appears as de Warenne, de Warrenne, de Varenne and de Warethna. (The family’s surname is said to be a reference to the village of Varenne, named for the river on which it was built.)

When Rudolph’s wife Emma bore him a son in 1036 – the year after Guillaume le Bâtard inherited the dukedom – he was named Guillaume in honour of his illustrious kin. The two Williams were only nine years apart in age, and grew up in a close-knit family which included William FitzOsbern, Roger de Beaumont and Roger de Montgomery, all of whom were descendants of Duchess Gunnora’s brother and sisters.

The boys grew up in a state of anarchy. The Norman aristocracy battled each other and outsiders for control of the young duke. Four guardians appointed to care for him died in swift succession, one being murdered in the boy’s bedchamber while he slept. It is said the duke’s uncle sometimes had to hide him in the houses of peasants to keep him safe.

Duke William needed powerful allies, and so he needed to marry well. He chose Matilda of Flanders, the French king’s niece. According to legend, when he sent his envoy to ask for Matilda's hand in marriage, she told the knight that she was far too high-born to consider marrying a bastard. After hearing this response, William rode from Normandy to Bruges, found Matilda on her way to church, dragged her off her horse by her long plait, threw her down in the street in front of her flabbergasted servants, and galloped away. After that, Matilda refused to marry anyone else. Not even a papal ban (on account of them being cousins) could dissuade her. They were married in 1051.

The king of France did not seem pleased at this rather violent romance. In February 1052, he led a double-pronged force against Normandy. Henry I led the main thrust through Évreux, while his brother Odo invaded eastern Normandy.

In response, Duke William divided his troops into two. He galloped to meet Henry to the west of the River Seine, while some of his supporters rode to face Odo.

William de Warenne was just eighteen years old, the younger of two sons, and eager to make his way in the world. He seized his sword, saddled his horse and rode off to fight for his cousin, the Bastard.

For hours, the battle raged. The French forces had not expected much resistance and the Normans took them by surprise. The French suffered heavy losses, and the capture of some of their most important leaders. When news of the Norman victory reached the other side of the river, the French king withdrew in disarray.

William de Warenne was rewarded for his loyalty and valour with land near a small village on the Varenne river, which winds its sinuous way through the meadows and forests of the Orne. He built a fortified castle high on a hill above the village, with two tall round towers guarding a drawbridge. The castle was named Bellencombre, the first syllable meaning ‘beautiful’ and the second from the Old French word ‘combre’ which means ‘barrier’ or ‘obstruction’.

At Bellencombre, William de Warenne was able to enjoy the peace he had so bravely helped to win.

New Star, New King

In 1066, Edward the Confessor, the king of England, died without naming an heir.

Four rivals claimed the throne.

The first was Edgar the Atheling, a sickly fourteen-year-old boy who was the grandson of Edward the Confessor’s half-brother. Although he was the closest in blood to the crown, he had lived in exile in Europe all of his life and had few friends in England.

The second was William the Bastard. He was the dead king’s first cousin, once removed, since his great-aunt Emma was Edward the Confessor’s mother. After Cnut invaded England in 1016, Edward had fled to Normandy and had lived there for many years. William the Bastard claimed that Edward had promised him the throne in thanks to Normandy giving him shelter for so long.

The third was Harald Hardrada (which means ‘hard ruler’.) He was a fierce and ambitious Viking who had won himself the throne of Norway, tried and failed to win the throne of Denmark, and so had set his sights on winning England’s. Harald Hardrada’s claim was flimsy as gossamer, but backed up by brute force.

Finally, the fourth claimant was Harold Godwinson, a powerful English nobleman who was married to Edward’s sister Edith. Although he had no royal blood, he claimed that he had promised Edward on his death-bed to take the crown and protect England. There were, unfortunately, no witnesses to this promise. Nonetheless, the assembly of English nobles and councillors voted to elect him king, unsurprisingly preferring a rich and powerful Englishman over a sick boy, an illegitimate Norman duke, and a voracious Viking marauder.

William the Bastard was annoyed. A few years earlier, Harold Godwinson had visited Normandy, either by mistake (he was shipwrecked on its wild coast), or by design (he was sent by Edward to confirm the offer of the crown to William.) The Normans claimed the latter, and also that Harold swore a sacred oath to uphold William’s claim on the English throne. This moment is immortalised in the famous Bayeux tapestry, with Harold (looking most unhappy) laying his hand on holy relics and swearing fealty to the Norman duke.

Harold Godwinson makes his oath of fealty to William, Duke of Normandy

Image source: bbc.co.uk

The Bayeux embroidery was commissioned by William’s half-brother Odo, and so cannot be relied on for historical accuracy. Nonetheless, the crowning of Harold as king of England prompted William to call his knights together and plan the invasion of England. Many of the nobles were hesitant about taking such drastic action. Normandy did not have a navy, and was surrounded by enemies on all sides.

However, in late April 1066, a bright comet was seen in the night sky. An observer in Italy wrote: ‘a comet … appeared in the West in the evening of the 24th and (shone) like the eclipsed Moon, the tail off which streamed like smoke up to nearly half the sky.’

When William saw it, he called it ‘a wonderful sign from heaven’, and convinced his barons that it was a sign of victory to come. The Norman knights took up a new rallying cry: ‘nova stella, novus rex’ which means ‘new star, new king’.

In England, the comet was seen with dread. One monk bowed down in terror and crying ‘thou threatenst my country with utter ruin.’ King Harold was said to have dreamed uneasily of ghostly ships.

Man-at-arms warning Harold of the disastrous omen of Halley's Comet.

Bayeux Tapestry, detail (ca. 1070–80).

Image source: Wikimedia Commons - Myrabella

William the Bastard set sail in mid-September 1066, after a night spent praying with his fifteen closest companions in the tiny church at Dives-sur-Mer. One of those companions was William de Warenne.

Meanwhile, Harald Hardrada had joined forces with the English king’s rebellious brother, Tostig, and landed an army in Yorkshire. King Harold marched with his army from London to repel the invaders. Although his soldiers were wearied after their long march, they attacked the enemy and – after a bitter and bloody battle – emerged victorious on 24th September. Both Harald Hardrada and Tostig were killed.

On 28th September, William and his knights landed in Pevensey, Kent.

On 1st October, King Harold and his exhausted soldiers marched three hundred kilometres back to the south of England. The two forces met at Battle, near Hastings, on October 14th.

At first, the Saxon two-handed axes carved through the chainmail of the Norman knights. On the second day of the battle, though, Harold was shot through the eye by an arrow (or so the story goes). His death disheartened the English forces, and soon the battle was won by the invading Normans.

On Christmas Day 1066, Duke William of Normandy was crowned King of England.

William de Warenne was one of the knights who fought at the Battle of Hastings, and he was rewarded richly for his courage and loyalty.

Almost immediately, he married Gundred, one of Queen Matilda’s ladies-in-waiting. Her tombstone at St. John's Church, Southover, Lewes, reads: ‘Within this Pew stands the tombstone of Gundrad, daughter of William the Conqueror, and wife of William, the First Earl of Warren.’

Much as I’d love to say that I was descended from William the Conqueror himself, there is no historical record of her birth and so most genealogists today think this claim is untrue. However, another branch of our family tree leads straight back to the Conqueror’s sister, Adelaide, which makes feisty Herleva the tanner’s daughter my great-grandmother-times-sixteen, a connection I’m proud to claim.

The Domesday book of 1086 shows that William de Warenne’s lands stretched over thirteen counties, from Conisbrough in Yorkshire to Lewes in Sussex, making him one of the richest men in the kingdom. In 1088, he was named the first Earl of Surrey. He did not, however, live to enjoy his earldom, dying later the same year.

His son William de Warenne, the second earl of Surrey, met a young woman named Isabel de Vermandois at a tournament and eloped with her, even though she was already married to Robert de Beaumont, the earl of Leicester. She had been married to him at the age of eleven and had given him nine children. Her husband is said to have died at shame at her wantonness, and she married William de Warenne II soon afterwards.

The blood of kings ran in Isabel’s veins. Her father was Hugh Capet, younger son of King Henry I of France. Her mother was Adelaide de Vermandois, descended from Charlemagne himself.

Their son and heir, William, the third earl, was born in 1119. He died on Crusade in Turkey whilst fighting in the elite royal guard of King Louis VII of France. His only child, a daughter, also named Isabel, became the greatest heiress in England. She too married brilliantly, with her second husband being Hamelin, the nephew of Henry II.

Isabel and Hamelin’s grand-daughter – also named Isabel – is known to history as the countess who chastised the king. In 1252, the king took one of her properties and granted it to one of his favourites. She confronted the king, asking: ‘Where are the liberties of England, so often recorded, so often granted, and so often ransomed?’

Henry III responded derisively, ‘curling his nostrils’, and asked who had given her permission to speak. Isabel argued that the king had given her the right to speak in the articles granted in Magna Carta, and accused the king of being a ‘shameless transgressor’. The king dismissed her angrily, but Isabel continued to fight for her rights through the courts.

Eventually the king wrote: ‘Henry, by the grace of God king of England … duke of Normandy and Aquitaine and count of Anjou sends greetings … Know that we have pardoned our beloved and faithful Isabella countess of Arundel ... by our seal of England, provided she says nothing opprobrious to us as she did when we were at Westminster.’

This spirit of independence and unwillingness to bow to authority saw the loss of the earldom a few generations later.

John de Warenne, the seventh earl, had inherited the title from his grandfather after his father died fighting in a tournament. He was married at the age of twenty to Joan of Bar, the ten-year old granddaughter of Edward I. However, John was in love with another woman, Maud of Nerford, the daughter of a Norfolk gentleman. Even when threatened with excommunication, John would not abandon his mistress. He tried to have his marriage to Joan annulled in 1314, both on the grounds of consanguinity (they were closely related by blood) and unwillingness.

A long legal battle followed. John was living openly with Maud, and they had several children together. The Countess Joan was living alone in the Tower of London at the king’s expense. In the end, though, the annulment was denied and John was excommunicated. The British Museum holds the registers of the archbishop of Canterbury which condemned ‘the brave and noble earl … for keeping Dame Mawd de Nereforde against the law of God and the order of the holy church, putting from him his deare wife.’

By the 1340s, both Maud Nerford and her sons had died, but John de Warenne had a new mistress named Isabella Holland. Once again he attempted to divorce Joan so that he could marry his mistress and legitimise their children. He was refused, however, and he died soon afterwards, in 1347, at the age of 61. Without a legitimate heir, the earldom was inherited by his sister’s son, the tenth Earl of Arundel. John de Warenne’s numerous illegitimate children were left with little more than a purse of coins each (though one of his sons, William de Warenne, also inherited a silver gilt helmet and armour).

The year after John de Warenne died, the Black Death was carried to England by fleas burrowing in the fur of rats. Millions of people died as a result, and parish records were left in chaos. This means there are a few gaps in the historical record.

A William de Warynge was noted in Staffordshire’s court rolls in 1386, after being caught fishing in a neighbour’s fishponds in Wyghtwyck (now called Wightwick), about four miles from Wolverhampton.

In 1419, a man named Nicholas Waring was included by the Sheriff of Staffordshire in a list of eligible knights ‘bearing arms from their ancestors for the service of the king in defence of the realm.’ He is believed to be the son of William Waring of Wolverhampton, a prosperous wool merchant.

Nicholas’s descendants were known as the Warings of the Lea, after their moated manor house in Wolverhampton. Our ancestor Charlotte Waring is directly descended from this branch of the family.

She certainly believed that she was descended from the first William de Warenne, the Norman knight who became the first Earl of Surrey. It is what she told her own children. Her eldest daughter Charlotte Elizabeth repeated it to her children, who passed it down through six generations to Binny and me. And her youngest daughter, my great-great-great-great-aunt Louisa, wrote it down for her own child, almost as if she knew she would never live to see her daughter grow up.

The only way to prove it for sure would be to do a DNA test on the crumbling bones of the first earl. He was buried at Lewes Priory in Sussex more than nine hundred and thirty years ago. The priory was destroyed by Henry VIII in the 1530s, and the graves of William de Warenne and his wife Gundred were thought lost. In 1845, however, a railway line was dug straight through the ruins of the priory and workmen dug up two small lead caskets containing human bones. They were reburied in a small Norman-style chapel built at St John the Baptist church in Southover, Lewes.

Somehow I do not think the church would approve of me asking for an exhumation!

I would have loved to have found that missing link from the 14th century that proved that the oral story we all inherited was true: that Charlotte Waring, the intrepid young governess who built a life for herself in Australia, was indeed related to that intrepid young Norman knight who fought at the Conqueror’s side almost a thousand years ago.

I spent many hours trying to find the connection. Once or twice my heart leapt as I found a mention in an antique book of pedigrees or a genealogical website, but always there was as much evidence to contradict the link as to prove it. The Wolverhampton Antiquarian, for example, published in 1933, says: ‘the family appears to be of very ancient origin. It is probably connected with … one Warine de Penne …’ (Penn is a parish of Wolverhampton, not far from where the Lea once stood).

And Ronald Waring, the 18th Duke of Valderano, wrote in response to a querying letter from Jan Gow, our second cousin: ‘I had always believed that the Warings of the Lea were descended from the third son of the third duke … (though) it is very possible that the Warings of Owlbury (and) the Lea are descended from us … from about 1335.’

So I did what any self-respecting amateur genealogist does these days – I spat into a tiny test-tube and sent it off to Ancestry.com. It came back with the most predictable results possible! The epicentre of my ethnicity is very firmly centred on southern-eastern England and north-western France i.e. Kent, Surrey, Sussex and Normandy!

When I began my investigation into the origins of the de Warenne family, I knew – from the family tree we all inherited – that my family was descended in one way or another from kings and tyrants.

I did not want to prove I was descended from William the Conqueror, or Charlemagne. After all, as Richard Dawkins has said, all living creatures are cousins. Go far enough back, and we humans are related to both orangutans and octopuses.

What I wanted was to discover was the stories behind the names and the dates. Tales of life and death, love and war, victory and defeat, happiness and heartbreak. It is these stories that connect us across the divide of a thousand years, and make us aware of our common humanity. Stories of our past shape our psyche.

What I most wished for was some kind of sign that my family’s irresistible compulsion to write had deep roots in the past. I have always wanted to be a writer. I say I was born knowing it was my one true destiny (and although I say it light-heartedly, I am not joking). I began scribbling stories and poems as soon as I could hold a pencil, and wrote my first novel – longhand in an old school exercise book – when I was only seven. By the time I had finished school, I had written half-a-dozen novels and innumerable poems and stories. My sister Binny and my brother Nick are the same. Between the three of us, we have published almost 90 books.

Where does it come from, this insatiable urge to write? Surely it is a part of us, like my dark hair and pale skin, like Binny and Nick’s chocolate-brown eyes. Surely it has been passed down to us, a chain link in the miraculous double-stranded spiral of our DNA.

‘I’m hoping for troubadours,’ I joke. ‘Surely somewhere in our ancestry is a wandering minstrel with a penchant for writing love poetry?’

So you can imagine how happy I was to discover that, in the twelfth century, a man named Aymon de Varennes wrote a long poem of adventure, magic and romance entitled Le Roman de Florimont. It tells the story of a brave young hero who confronts the giant Garganeus, marries the beautiful princess Romandaaple, and frees her father, the king, from prison. It was one of the most popular romances of the medieval period.

Aymon de Varennes’s ancestry is unknown, and it is impossible to say with any certainty that he was descended from the same stock as my ancestor, William de Warenne.

But I like to think he was.