Last week I did an hour-long interview with Richard Fidler on his hugely popular ABC Radio Show 'Conversations' (click the link to listen to the whole interview). Among other things, I spoke about my great-great-great-great-grandmother, Charlotte Waring Atkinson, who wrote the first children's book published in Australia. I have had such a huge response from the show, and so many questions about this incredibly strong, brave and clever woman, that I decided to post an article I wrote for Australian Author some years ago to celebrate the 170th anniversary of the book's publication:

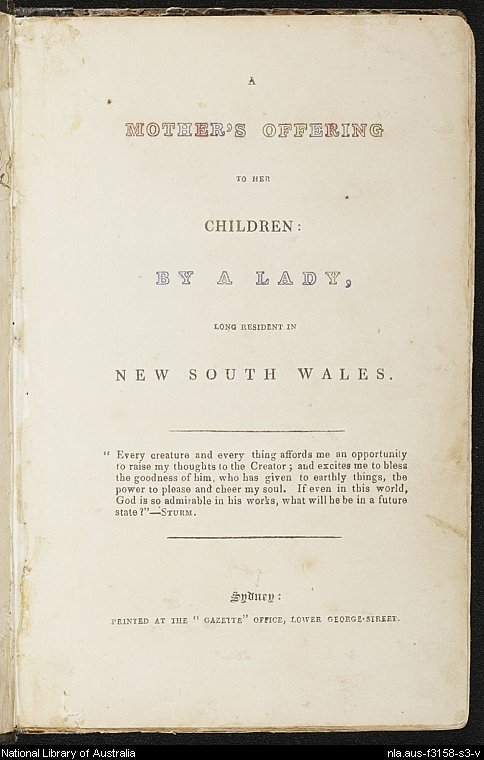

Frontispiece of the first edition of A Mother's Offering To Her Children by A Lady Long Resident in New South Wales, first published in 1841

‘Heirs of Immortality’

Who was the mysterious ‘Lady’ who wrote Australia’s first children’s book?

Nowadays, Australian children’s authors such as Shaun Tan, Melina Marchetta, Sonya Hartnett, John Marsden, and Garth Nix are as well-known internationally as they are here.

Yet how many people know the name of Australia’s first children’s writer?

A Mother’s Offering to Her Children was published 174 years ago by a woman known simply as ‘A Lady Long Resident in New South Wales’. For almost a century and a half, her identity was Australia’s most puzzling literary mystery. In the 1960s, Marcie Muir - a passionate lover of Australian children’s literature - set herself the task of finding out who this anonymous ‘Lady’ was. She could never have anticipated that she would uncover one of the great lost stories of Australian history, a tale of courage, grief, violence, and triumph in the face of overwhelming odds.

So who was the ‘Lady Long Resident in New South Wales’?

She was a child prodigy who could read by the age of two.

She was a fiercely independent young woman who scandalised Sydney society with her determination to forge her own way.

She was a widowed mother of four who singlehandedly ran one of the largest land grants in early New South Wales.

She was probably raped by an infamous bushranger, the man later dubbed the Berrima Axe Murderer.

She was a battered wife who fled her “raving lunatic” of a second husband, even though it left her homeless and penniless.

She was the mother of the first Australian-born female novelist.

She was also my great-great-great-great-grandmother.

Marcie Muir (1919-2007) was a collector and bibliographer of Australian children’s books whose passion became an obsession. Her library of over 7000 books – many of them extremely rare – was bought last year by the National Library of Australia. There was one book, though, that she was never able to afford to buy. A first edition of A Mother’s Offering To Her Children is now valued at $60,000. Even sixty-odd years ago, it was worth more than Marcie Muir could afford to pay.

In 1978, a second edition was printed by Jacaranda Press, with a foreword by Rosemary Wighton, author of Early Australian Children’s Literature. She says, ‘For many years it was believed, because of a hand-written note in one of the surviving copies, that the author was Lady Gordon Bremer ... This attribution now seems increasingly dubious ... a letter from one of Lady Gordon Bremer’s descendants to the bibliographer of Australian children’s books, Marcie Muir, states that, as far as family records show, she never visited Australia at all.’

When this second edition was published, Marcie Muir had already spent almost a decade trying to identify the author of A Mother’s Offering, searching through ancient newspapers, scrolling down endless microfiches, and writing to anyone who might be able to help.

One day, in the summer of 1978, her doggedness at last paid off. Marcie Muir had flown to Sydney to look through Mitchell Library’s newspaper archives, in particular those of 1841, the year A Mother’s Offering was published. In The Sydney Gazette, on the very last newspaper of the year – 23 December 1841 – she found a small review tucked away at the back.

It said: ‘(A Mother’s Offering to Her Children), which embraces a variety of useful and entertaining matter, is got up under the form of dialogues between a mother and her children. It is to be hoped that others will follow the noble example set up Mrs Barton ... nothing sooner gives young persons a taste for refined literature than books ... which while ... interesting, are also instructive.’

A name! ‘Mrs Barton.’ Yet who was Mrs Barton?

Nobody seemed to know. For another eighteen months, Marcie Muir tried to find out. Eventually, wearied of her task, she gave up and turned her attention to another literary mystery – identifying the author of the first illustrated children’s book, Peter Possum’s Portfolio.

Finding an advertisement for it in the back of Cowanda, the Veteran’s Grant, an 1859 novel by the colonial writer Louisa Atkinson, Marcie Muir wondered if she could also have been the author of Peter Possum’s Portfolio. Louisa Atkinson was an accomplished novelist, artist and naturalist, and well-known as Australia’s first native-born female novelist.

Marcie Muir began to research Louisa Atkinson’s life and work. To her astonishment, she discovered that Louisa Atkinson’s mother – born Charlotte Waring – had remarried a man named George Barton when Louisa had been only four.

Could the mother of Australia’s first native-born female novelist also be the author of Australia’s first published children’s book?

The idea fascinated Marcie Muir. She plunged into research on the Atkinson family and eventually made contact with the descendants of the Atkinsons, who had many drawings and papers which were able to conclusively prove that it was indeed Louisa Atkinson’s mother who was the mysterious ‘Lady’ Marcie Muir had been searching for.

Born in 1796, Charlotte Waring was the third of four sisters. Her mother died giving birth to her younger sister, and Charlotte was raised by her father, a man of fortune whose ancestors had come to England with William the Conquerer. Charles Darwin was her fifth cousin, and her father, Albert Waring, was a younger son of Lord Saye and Sele. Charlotte was a brilliant child who could read fluently at the age of two and who received an unusually good education.

When she was fifteen, her father died, and Charlotte’ young half-brother inherited all his wealth and property. Charlotte and her sisters were left impoverished and, like many a heroine of a Bronte novel, were forced to find work as governesses.

Yet Charlotte was strong-willed and strong-minded, and used to a life of privilege. When a position was advertised for the princely price of 100 pounds a year, Charlotte leapt at the chance. Unlike the 24 other applicants for the job, she was not daunted by the idea of travelling halfway round the world to the tiny colony of Sydney, although she had read newspaper accounts of attacks by savage natives with spears, escaped convicts, bushfires, and smallpox epidemics.

She had one stricture. She would only go if she travelled first class.

At first Mrs King, the wife of Admiral Phillip Parker King, was effusive in her praise of the governess she had hired for the Macarthurs. A few weeks later, however, she wrote to her husband, “I am very much disappointed in Miss Waring the Governess, she is very different from what she ought to be ... We had not been 2 hours on board before I saw she was flirting with Mr Atkinson, and ere 10 days were over she was engaged to him … she told me … she must be mistress of her own actions.’

Charlotte Waring left Plymouth on 19th September 1826, a penniless governess with few prospects. She arrived in Sydney on 22nd January 1827, engaged to James Atkinson, a rich gentleman-settler.

James Atkinson had landed in Sydney in 1820, only thirty-two years after the arrival of the First Fleet. He had been given two land grants totaling 2,000 acres as a reward for his services in the Colonial Secretary’s Office. This land, called Oldbury after his father’s manor in Kent, was at Sutton Forest, 140 kilometres south of Sydney. He was good friends with the Kings and the Macarthurs, and his book, An Account of Agriculture and Grazing in NSW, had just been published in London to great acclaim.

Their romance scandalised Sydney. Alexander Berry, writing to Edward Wollstonecraft, said ‘I must say I never saw a lady whose manners were less to my taste … the grossest levity!’ Mrs King wrote ‘she behaved very ill and gave herself many airs’, though, as Marcie Muir was to write, ‘there is more than a little malice in Mrs King’s tone, inspired by her disapproval of the governess she had engaged daring to become betrothed to a gentleman of their acquaintance.’

Charlotte and James were married on 29 September 1827 and went to live at Oldbury, where they built a grand sandstone manor which still stands today (though not, sadly, owned by my family). Four children were born in quick succession - Charlotte Elizabeth (my great- great-great-grandmother), Jane Emily, James John Oldbury and Caroline Louisa Waring (known as Louisa).

A photo of Oldbury Farm as it is today, taken by my sister Belinda Murrell

When Louisa was only two months old, James died and Charlotte was left alone, the mistress of a vast, isolated property worked by convicts and the mother of four children under the age of six. In a repeat of her childhood tragedy, Oldbury was left in trust for her son, then only two years old.

Almost two years after James’s death, Charlotte and her overseer, George Barton, were visiting an outlying property when they were held up and robbed by bushrangers, led by the notorious escaped convict John Lynch, later to be named the Berrima Axe Murderer. Lynch whipped Barton cruelly, saying he “considered it his duty to … flog all the gentlemen so they might know what punishment was.”

A drawing of the infamous bushranger and Berrima Axe Murder, John Lynch

Charlotte herself may have been raped. Since she never spoke of that day, we cannot be sure but certainly her own family came to believe so. Whatever happened that terrible day, it led Charlotte to make the greatest mistake of her life.

One month later Charlotte married George Barton. He was a violent drunk. When asked to testify against Lynch in a court of law, he turned up so incapacitated by alcohol that Lynch was acquitted and went on to murder another ten people. Louisa Atkinson was to write of her step-father: ‘(he) became a furious maniac and had to be kept under restraint.’ In time Barton would be charged with murder, and sent to gaol.

After three terrible years, Charlotte and her four young children fled Oldbury. They took only their clothes, Charlotte’s jewellery box, the children’s pet koala, and her writing desk, tied to the back of a bullock. They travelled at night down the precipitous Meryla Pass and through the wild gorges of the Shoalhaven River, at last reaching Sydney some months later. Charlotte had no income at all from Oldbury, supporting her family by the sale of her clothes and jewellery, and by running up debts.

For the next six years, Charlotte would fight not only for the allowance she was entitled to under her dead husband’s will, but also for custody of her children. The executors of the will – Alexander Berry and John Coghill – maintained she was ‘not a fit and proper person to be the Guardian of the Infants … in consequence of her imprudent … intermarriage with George Bruce Barton.’ This accusation must have been a bitter pill for Charlotte to swallow, as she had run away from her violent husband and had already applied to the courts for protection from him.

In the meantime, Charlotte had to find some way to house, feed, clothe and educate her children who were ‘literally starving’. So she wrote a book, the first children’s book to be published in Australia. It was released in December 1841, in time for the Christmas trade. Cleverly, A Mother’s Offering was educational enough to appeal to early Victorian sensibilities and yet still exciting enough to appeal to children, filled as it was with descriptions of storms, shipwrecks, strange animals, fossils and cannibals. It was an instant bestseller, and provided Charlotte with an income until her son was at last old enough to inherit Oldbury.

Structured as a dialogue between a mother and her four young children, the book is hard to read now, with all its moral instructions and outmoded Victorian sensibilities. Yet it was the first book in the world to draw upon Australian history, the first to feature native trees, birds and animals, the first to describe life as a settler, the first to feature the life and culture of the Australian Aborigines. I have to remind myself of this because, I must admit, the first time I read it I was horrified at her racism. It is hard to remember that Charlotte was writing in the early 19th century, and that her depiction of “the natives” was considered rather too sympathetic at the time.

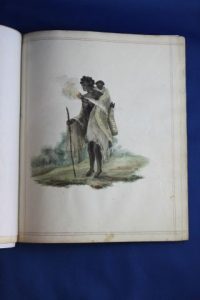

A sketch of a local Aboriginal woman with her child, drawn by Charlotte Waring Atkinson

By the time the book was published, Charlotte had resoundingly won her case, though she was fined in court for her ‘impertinence’. The Chief Justice, Sir James Dowling, ruled: “It would require a state of urgent circumstances to induce the Court to deprive them (all of whom are under thirteen years of age) of that maternal care and tenderness, which none but a mother can bestow.”

A Mother’s Offering To Her Children was based on stories that Charlotte had told her own children, who had lost everything - their father, their wealth, their home. She told them stories to teach them, to entertain them, and to comfort them. With her stories, she created an enchanted circle where those four fatherless children knew that they were loved.

Charlotte Waring wrote in her final paragraph of A Mother’s Offering to her Children: ‘we know not the day, nor the hour, when time may cease for us; and we be summoned into eternity. Let us, dear children, endeavour to profit by the frequent warnings we have of the uncertainty of life … (Let us) so pass through this life that we gain a knowledge of the things which belong to our peace; and become at last heirs of immortality!’

To celebrate the 170th anniversary of the publication of her book, the Children’s Book Council of Australia (NSW Branch) has announced they plan to rename the Frustrated Writers’ Award in her honour, so that her name – unknown for so long - shall at last be remembered.

(The primary sources for this article were Charlotte Barton: Australia’s First Children’s Author by Marcie Muir (Wentworth Books, 1980), Pioneer Writer - The life of Louisa Atkinson: novelist, journalist, naturalist by Patricia Clarke (Allen & Unwin, 1990) and oral history passed down by the descendants of James and Charlotte Atkinson.

My sister has written a wonderful novel about the Atkinsons entitled The River Charm, which I hope you will all read.

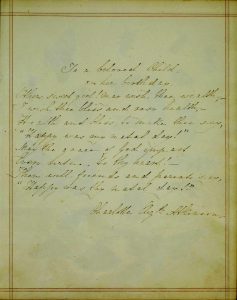

And just finally, a note in regards to Charlotte's name. As a result of Marcie Muir's book, Charlotte is known as Mrs Barton ... but my great-great-great-grandmother hated and feared her second husband, took out a restraining order against him, and never called herself by that name. To the time of her death, she called herself Charlotte Atkinson, as can be seen by this sketchbook she made for her eldest daughter, also called Charlotte. No-one in the family would ever call her by the name Mrs Barton, and we all hope that others will respect her wishes and not call her that either!