1)The original Russian tale of Vasilisa seems rather bizarre. What compelled you to re-tell it?

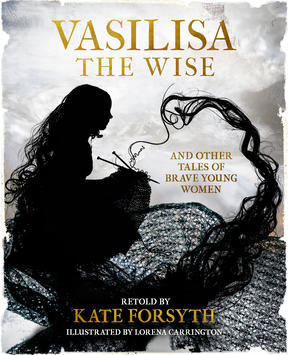

It’s the best-known Russian fairy-tale, akin to ‘Cinderella’ in Western culture, and tells the story of a brave and clever girl who saves her own life by outwitting the dark cannibalistic witch Baba Yaga. The images in the story – the little wooden doll that comes to life, the witch flying in a giant mortar, the hut with chicken legs – are just so unique and memorable. When Lorena Carrington and I began to collaborate, she had already done quite a lot of work on this tale, but it was one I have always loved as well and was eager to include.

2) All of the stories in Vasalisa the Wise are based on ‘little known tales’. Where did you discover these obscure fairy tales? What myths and legends did you draw inspiration from?

Both Lorena and I have been collecting and studying fairy-tales for years, and each tale was important to us for different reasons. For example, I first discovered the story of ‘Katie Crackernuts’ (an old Orkney tale) when I was in Scotland with my family and bought a version of it in a cobwebby old second-hand bookshop. Lorena knew the story of the Prince-Serpent, which comes from Norway, but I had never read it before so it was a new discovery for me. ‘The Singing, Springing Lark’ is a beautiful German version of ‘Beauty & the Beast’ which I found while studying the Grimm Brothers for my doctorate in fairy-tale studies. It has a far more active heroine than the original French version and I always thought it was a shame it was not better known. And I stumbled upon the ‘The Toy Princess’, a literary tale written by the Victorian author Mary de Morgan, while researching a novel I was writing about the Pre-Raphaelites.

3)What kinds of research did you need to conduct in order to retell these stories?

I always like to trace the story back to its earliest versions, which are often oral tales collected by folklorists, just so I can see the tale within its milieu and think about how it might have been told originally. I also like to compare different versions of the tale, and then take the elements that speak most strongly to me and recombine them in new ways. There are literally dozens of versions of ‘Vasilisa’, for example. I read as many as I could find, and took a scene from one and a rhyme from another, and put them all together in the way I liked best.

4) What was the most challenging or restricting part of writing the stories in Vasilisa the Wise?

Some of the original stories were very long, and needed to be cut hard to make sure that all the stories in the book were of equal length. That is always a challenge because you don’t want to lose the unique style or flavour of the story.

5) Who do you think is the most formidable heroine in Vasilisa the Wise?

My own personal favourite tale is ‘The Singing, Springing Lark’, which is a favourite of mine to tell in a live performance of oral storytelling. (I told it at the Sydney Writers Festival last year.) The heroine of that tale must follow her beloved for seven years, with no more than a drop of red blood and a single white feather to guide her every seven steps. Then she must battle with the evil enchantress who cursed her beast-husband to break the spell upon him. I love her courage and her steadfastness, and the repetition of the refrain through the tale: ‘I have followed you for seven years, I begged news of you from the sun and the moon and the wind. Have you forgotten me?’

6) At what point did you become frustrated with the trope that fairy tale princesses are often in need of saving?

I’ve loved fairy-tales all my life, and have read and studied them since my first degree. It feels like I’ve been defending them all these years. So many people base their understanding of the genre on Disney movies, and in particular on the earliest retellings the studio made between 1937 and 1959, or they remember the dreadful Ladybird Classics published from 1964 onwards. For years I’ve tried to point out that Disney’s ‘Sleeping Beauty’ – in which the titular princess has only eighteen lines of dialogue – does not reflect the mythic roots of this ancient tale, in which the princess is a powerful force for life and resurrection. ‘Rapunzel’ is routinely criticised for being ‘a passive princess waiting for her prince’, even though in the original story she actually saves the prince from blindness and helps the witch find redemption. Most people also only know the tales of Charles Perrault, the Brothers Grimm, and Hans Christian Andersen, all of whom retold older tales in a patriarchal mode, draining the power of agency from the heroines. That’s why a project like Vasilisa the Wise & Other Tales of Brave Young Women is so exciting – we have the chance to bring the lost and forgotten stories of female empowerment back to the world.

7) Your novels The Beast’s Garden and The Wild Girl have also been inspired by fairy tales. What makes fairy tales so enticing?

Fairy tales really are as ‘a tale as old as time’, as Mrs Potts sings in the Disney movie ‘Beauty and the Beast’ (which, by the way, is my favourite Disney adaption). Every culture has invented these stories of love and transformation and triumph. Every child has grown up on them, from half-remembered stories told by exhausted fathers in the dead of the night to tattered storybooks handed down through the generations. Fairy tales give us a universal language of symbol, motif and metaphor to think and communicate with, and they teach us essential lessons about how to move through the world. The importance of kindness, the need to look below the surface, the right to choose our own path, the redemptive power of love – these are the key ingredients of all good fairy tales.

8) What do Lorena Carrington’s illustrations add to your stories? Do you have a favourite?

I had wanted to work on a collection of retold fairy tales for a long time, but I knew that I wanted the illustrations to reflect the darkness and the light, the peril and the beauty, the strangeness and the wildness of the tales. I discovered Lorena’s work quite by chance, and it had exactly the kind of eerie magical feeling that I wanted. I bought the starlit image of the mother stringing a harp with her own hair which appears on page 81 and it hangs in my hallway where I can see it every day. But my favourite image is the girl with the lion on p65, illustrating my favourite tale ‘The Singing, Springing Lark’. The model is my daughter Ella and I love how the lion is made from scraps of leaves and bark and moss.

You may also love to read my writing blog on Mary de Morgan:

https://kateforsyth.com.au/writing-journal/vintage-writing-post-mary-de-morgan