I have a page on my website I call The 50/50 project. It’s a list of 50 things I want to do before I die (though some of them are most unlikely to happen!)

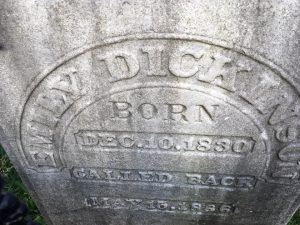

I’m gradually ticking things off. In late June 2017, I managed to make one lifelong dream come true: I made a pilgrimage to Amherst to visit the home of one of my favourite poets, Emily Dickinson.

I have been intrigued by her life and work ever since my high school English teacher told me that she had written 1800 poems, many of which were discovered after her death by her sister, transcribed on scraps of paper, old envelopes, the backs of recipes, on chocolate wrappers. Only ten of her poems were published in her lifetime, all anonymously. She wrote in one letter that publication was as ‘foreign to my thought, as Firmament to Fin.’

Here is a longer extract from the poem, written 7 June 1862:

‘I smile when you suggest that I delay "to publish" - that being foreign to my thought, as Firmament to Fin - If fame belonged to me, I could not escape her - if she did not, the longest day would pass me on the chase … My Barefoot-Rank is better …The Sailor cannot see the North - but knows the Needle can –‘

I often think of this letter when I find myself longing for fame (or at least for universal critical acclaim). My barefoot rank is better, I tell myself.

A great many of Emily’s most intense and powerful poems were written to her brother’s wife, Susan Dickinson, who had been her greatest friend and – perhaps – her lover (not that my English teacher told me that).

Emily was also agoraphobic. The circle of her life gradually narrowed around her until – as she wrote in 1858 – ‘I do not cross my father’s ground to any house or town.’ Sometimes she lowered a basket of cakes down to the local children from her bedroom window, where she sat at her tiny desk and scribbled her extraordinary poems.

This is how she described the passing of a circus through Amherst: 'Friday I tasted life. It was a vast morsel… Still I feel the red in my mind.'

My English teacher also told me that Emily Dickinson only ever wore white. I saw her only surviving dress at the Emily Dickinson Museum – it is pristine white and has deep pockets so she could carry around a notebook and pencil at all times. It is tiny. Emily must have been only 5’3” or less.

This small, white-clad, reclusive poet fascinated me. Being shy and home-loving, and always scribbling poems, I saw something of myself in her. I could imagine my sister discovering thousands of poems hidden in a box under my bed when I died, and then the world declaring me a genius too.

As a consequence, I began to read her poems which are like tiny packets of gunpowder.

Here are three of my favourites:

Poem 1129

Tell all the truth but tell it slant —

Success in Circuit lies

Too bright for our infirm Delight

The Truth’s superb surprise

As Lightning to the Children eased

With explanation kind

The Truth must dazzle gradually

Or every man be blind —

Poem Number 254

Hope is the thing with feathers

That perches in the soul,

And sings the tune without the words,

And never stops at all,

And sweetest in the gale is heard;

And sore must be the storm

That could abash the little bird

That kept so many warm.

I’ve heard it in the chillest land,

And on the strangest sea;

Yet, never, in extremity,

It asked a crumb of me.

Poem Number 764

My Life had stood – a Loaded Gun –

In Corners – till a Day

The Owner passed – identified –

And carried Me away –

And now We roam in Sovreign Woods –

And now We hunt the Doe –

And every time I speak for Him

The Mountains straight reply –

And do I smile, such cordial light

Opon the Valley glow –

It is as a Vesuvian face

Had let it’s pleasure through –

And when at Night – Our good Day done –

I guard My Master’s Head –

’Tis better than the Eider Duck’s

Deep Pillow – to have shared –

To foe of His – I’m deadly foe –

None stir the second time –

On whom I lay a Yellow Eye –

Or an emphatic Thumb –

Though I than He – may longer live

He longer must – than I –

For I have but the power to kill,

Without – the power to die –

Another item on my list is to see where the Bronte sisters grew up and wrote their books: